The killer loved his kids

Kampala -- Long before I met Joseph Kony I knew his handiwork. I had covered attacks by his Lord Resistance Army rebel group in Uganda for years, including one in 1996 that will stay with me forever. It was in the village of Acholpii, where his henchmen massacred some 100 people. As in other LRA raids, the village was burned and bodies were scattered all over. But that’s not what struck me. As I walked into the bush at the edge of the village, I saw a baby, alive and sucking at the breast of his mother. Who was dead.

The LRA had razed plenty of villages like this. In April the previous year 300 people died in Atiak, in February 2004 more than 200 would die in Barlonyo. Kony, a self-styled mystic and prophet, launched a bloody rebellion against Kampala some three decades ago, seeking to impose his own version of the Ten Commandments on northern Uganda. Since then, his LRA has slaughtered more than 100,000 people and abducted some 60,000 children.

A victim of the Lord's Resistance Army at a camp for the internally displaced in northern Uganda, February, 2004. The attack in which she was wounded left more than 200 civilians dead. (AFP / Peter Busomoke)

A victim of the Lord's Resistance Army at a camp for the internally displaced in northern Uganda, February, 2004. The attack in which she was wounded left more than 200 civilians dead. (AFP / Peter Busomoke)The LRA was pushed out of Uganda around 2004. Before the eviction, a series of failed peace talks were held with Kony and his lieutenants -- that’s when I met him and his top commanders, including Dominic Ongwen, who this week went on trial at the International Criminal Court at The Hague on 70 charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity, the first LRA member to ever go on trial.

When the peace talks were announced I scrambled to get there. ‘There’ turned out to be a Congolese hamlet few people could locate on a map. The first leg of the journey to get there took place in a UN Antonov, to the notorious town of Maridi in South Sudan. We landed in heavy rain, with the nervous Russian pilots not even turning off the engines, so that they could leave the lawless town as fast as possible.

I sheltered in a bar where South Sudanese soldiers traded their bullets – measured out in plastic cups – for the same volume of moonshine gin or bottles of Ugandan beer. Afterwards they staggered off into the darkness, assault rifles and light machine guns dangling from their shoulders as they swigged their drinks and threatened to shoot anyone who stood in their way.

Ugandan soldiers on patrol in April, 2012, as they hunt for Kony in the jungle.

(AFP / Stringer)

Ugandan soldiers on patrol in April, 2012, as they hunt for Kony in the jungle.

(AFP / Stringer)The next day we travelled further into the unknown, by 4x4 towards the place where South Sudan, Congo and CAR meet and where Kony had agreed to meet the press and the peace delegates. If it can be called a road at all, it was without doubt the worst I have ever seen, not that it slowed our South Sudanese military drivers (some of whom I’m sure I recognised from the bar the night before and some of whom drank beer as they drove).

Branches and thorns tore at my clothes as I bumped along in the back of the pick-up, clinging hard to the side. On at least three occasions different drivers rolled their vehicles over, sending passengers and possessions flying.

After a long day we reached an isolated South Sudan army camp called Nabanga and were offered abandoned, flea-ridden huts without doors to sleep in. For the next four days sacks of maize were my mattress and pillow, and biscuits and water were my meals as we waited for Kony. He never showed up.

The northern Ugandan village of Amuru, home to many survivors of LRA attacks, August, 2010. (AFP / Marc Hofer)

The northern Ugandan village of Amuru, home to many survivors of LRA attacks, August, 2010. (AFP / Marc Hofer)Despite the disappointment I tried again when another opportunity arose. This time the UN airlifted us to Nabanga, avoiding the drunken high-speed drive through the forest. From there we drove deeper into the jungle to a place called Ri-kwangba where Vincent Otti, Kony’s number two and himself an alleged notorious murderer, was waiting for us.

An LRA fighter during the talks in Ri-Kwamba, southern Sudan, November, 2006.

(AFP / Stuart Price)

An LRA fighter during the talks in Ri-Kwamba, southern Sudan, November, 2006.

(AFP / Stuart Price)When we got there, dreadlocked young LRA rebels searched us, then disappeared with our bags as the march began. It was a fearful six-hour walk through forest and across rivers. What if Kony changed his mind and killed us all?

As darkness fell we reached a clearing that was the LRA’s main camp. It nestled beneath dense forest cover, with a high rock shielding its northern side and another on its eastern flank which doubled as a lookout. A spring on top of one of the rocks was said to be a sacred place for Kony. The water issuing from it was pristine, clear and cold, gushing into a narrow gorge overlooking the camp. In another clearing there were gardens of sweet potatoes, beans and vegetables. In a way, it was idyllic.

We were told to wait and ordered not to use phones or cameras until given permission to do so. A fire was lit as the temperature dropped.

Later, I was shown to a thatched shelter where a basin of warm water had been placed outside along with a bar of soap, a towel and a sponge. As I washed I wondered how I would find my way back to Uganda if things went wrong. I wondered whether the rebels would kill us in the night or if the Ugandan army would launch an assault. I wondered whether Kony would show up this time around.

We ate a dinner of rice, maize bread, sweet potatoes, fresh vegetables and smoked game meat. It was a welcome change from the dry biscuits of the previous Kony expedition. After supper I spoke with Otti by the fire. He was curious about life in Kampala, the Ugandan capital.

Vincent Otti, number two in the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA), addresses journalists at Ri-Kwangba, September, 2006. (AFP / Stringer)

Vincent Otti, number two in the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA), addresses journalists at Ri-Kwangba, September, 2006. (AFP / Stringer)It was shortly after dawn when I saw Kony. He was behind a grass fence, wearing a T-shirt and an army cap, and playing with a baby who looked to be just a few months older than the one I had found suckling at his dead mother’s breast in Acholpii.

The time had come at last to meet this notorious warlord and his top commanders, including Okot Odhiambo and Dominic Ongwen who, like Kony and Otti, were wanted for war crimes by the ICC. Today, only Ongwen has been arrested after turning himself in. Kony remains at large, while Otti and Odhiambo are believed dead.

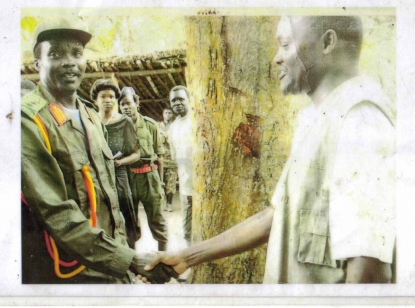

We drank tea together but spoke little. Ongwen was especially quiet and guarded. When Kony finally appeared he had changed into full military gear. We shook hands.

The author (r) shakes hands with Kony during their meeting. (Photo courtesy of Grace Matsiko)

The author (r) shakes hands with Kony during their meeting. (Photo courtesy of Grace Matsiko)During a rambling two-hour speech Kony – who claims spirit guidance – was frequently incoherent and prone to sheepish laughter. He denied killing people, claiming instead that he was “fighting for my people” meaning the Acholi tribe of northern Uganda. Otti later clarified that sometimes people might “die during crossfire”.

We stayed for days as efforts to start formal peace negotiations between Kony and the Ugandan government dragged on, and the LRA fighters and leaders got used to us being around. One evening Kony joined us as we watched a Jackie Chan kung-fu movie on Otti’s portable DVD player. I don’t remember which movie it was, but I remember that he often giggled, laughed and stamped his feet as Jackie Chan delivered punches to his opponents.

The day after, we began the long journey back to Kampala. The talks, sadly, did not result in peace and although the Ugandan massacres I once reported on have stopped in Uganda, the violence continues elsewhere -- after being pushed out of Uganda, LRA continues to terrorize part of the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Central African Republic.

Residents return to their villages around the northern Ugandan town of Lira. Because of frequent raids on villages by the LRA, many residents come to Lira to spend the night, often on porches of shops. November, 2003. (AFP / Marco Longari)

Residents return to their villages around the northern Ugandan town of Lira. Because of frequent raids on villages by the LRA, many residents come to Lira to spend the night, often on porches of shops. November, 2003. (AFP / Marco Longari)Meeting in person some of the world’s most wanted men was a surreal experience. As I shook hands with him, I thought of the hundreds, if not thousands, of people who had been brutalized because of those hands. When our eyes met, he looked nervous and looked away. He appeared to be engrossed in his own world most of the time, but enjoyed the company of others.

But it was a rewarding experience as well, because it helped me to better understand the conflict and its players. I never expected Kony, a man allegedly responsible for so much death and suffering to be loving with children. But he was. His numerous wives and children were at the compound when we were there and I often saw him playing with his children. He bounced one on his knee and carried others around on his chest.

He had several wives and the children had nannies, mainly young girls who had been abducted from their homes and who would eventually become his wives too.

Former Kony wife Evelyn, 23, with her daughter Mercy in northern Uganda, February, 2006,. Kony kept her in captivity for 10 years, during which she was often beaten and terrorized. (AFP / Jose Cendon)

Former Kony wife Evelyn, 23, with her daughter Mercy in northern Uganda, February, 2006,. Kony kept her in captivity for 10 years, during which she was often beaten and terrorized. (AFP / Jose Cendon) Former Kony wife Margret, 33, in northern Uganda, February, 2006. She was also kept in captivity for 10 years following her kidnapping. (AFP / Jose Cendon)

Former Kony wife Margret, 33, in northern Uganda, February, 2006. She was also kept in captivity for 10 years following her kidnapping. (AFP / Jose Cendon)

He laughed. It was rare, but he would usually burst into laughter unexpectedly. He didn’t smoke or drink alcohol, but he served me locally-made brown wine, which he said was made from sap from trees in Garamba and that he said he served only to his most valued guests. It was sweet and it made me tipsy for a little while, but that quickly vanished, leaving a sour taste in the mouth. He was a very good host, asking me if I had eaten.

I may not be covering the LRA actively anymore, but the story is not over for me. The next step for me -- and many in northern Uganda -- will be listening to Ongwen’s testimony during his trial at The Hague and following the course of justice for LRA’s victims, like that mother all those years ago whose baby was orphaned in the village of Acholpii.

This blog was written with Yana Dlugy in Paris.

A woman follows pre-trial proceedings against Kony lieutenant Dominic Ongwen at the International Criminal Court from the Lukodi district of Gulu in Uganda, January, 2016.

(AFP / Isaac Kasamani)

A woman follows pre-trial proceedings against Kony lieutenant Dominic Ongwen at the International Criminal Court from the Lukodi district of Gulu in Uganda, January, 2016.

(AFP / Isaac Kasamani)