The rape camps of South Sudan

Bentiu, South Sudan, October 6 -- I went to South Sudan looking for war crimes, and found them.

One woman I spoke to was called Nyamai, a 38-year-old mother of five. She was taken from her village in Unity State in April during the latest government offensive in a nearly two-year-old civil war. Like hundreds of other women, she was abducted by armed men, marched for days, guarded constantly and tied up frequently. At night, as many as 10 soldiers would queue up for their turn to rape her.

"Please, let one guy deal with me, don't come all of you," she pleaded. In response, she was beaten with a stick.

Dozens of interviews conducted over six days in a protected site for people uprooted by the war revealed a systematic pattern of abductions and sexual abuse, with women and girls giving horrific testimony of their suffering in rape camps where some were kept, under guard, for days, weeks or even months.

It’s one of the most appalling stories I’ve ever reported, from any country.

Unity State from the air (AFP / Hannah McNeish)

Unity State from the air (AFP / Hannah McNeish)I’ve been visiting South Sudan since 2005 when a peace deal ended generations of conflict and put the country on the path to independence six years later. Progress was slow, faltering and gradual but it was there–along with a great deal of optimism–until December 2013 when it ended.

That December, the country’s two most powerful political leaders–both former military commanders–went to war over who would control the ruling party and with it, the country and the right to plunder its resources, chiefly oil.

South Sudan President Salva Kiir (L) and leader of the largest rebel group and former vice-president Riek Machar (R) (AFP / Simon Maina - Ashraf Shazly)

South Sudan President Salva Kiir (L) and leader of the largest rebel group and former vice-president Riek Machar (R) (AFP / Simon Maina - Ashraf Shazly)It didn’t take long for their armed forces to bludgeon the young country into a worse state than when I had first visited. It’s not so much the physical damage to infrastructure, as the social destruction of a civil war that has plumbed new depths of brutality and fratricidal violence.

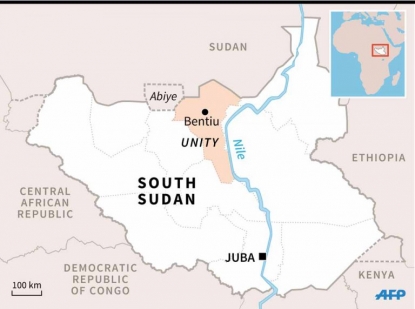

Some of the worst of it happened earlier this year in Unity State, a huge expanse of swamp, forest and oil fields in the north of the country, bordering Sudan.

The location of Unity State inside South Sudan. (AFP Graphics)

The location of Unity State inside South Sudan. (AFP Graphics)Reports of atrocities began to trickle out while the government’s April-July offensive was still underway.Human Rights Watch and the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) produced alarming catalogues of attacks that shared common features: women were raped, often by more than one armed man, and killed, sometimes by hanging from trees; children were murdered, especially the boys; homes were burned, sometimes with people inside; boys were recruited as child soldiers and girls as porters; entire villages were razed; there was widespread looting of meagre possessions and valuable cattle.

I wanted to go to Unity to report on what seemed plainly to be war crimes. I hoped that it would allow me to capture for readers something of the nature of the conflict and to turn up the volume a little so more attention might be focused on South Sudan’s civil war.

A UN base outside Bentiu from the air. (AFP / Tristan McConnell)

A UN base outside Bentiu from the air. (AFP / Tristan McConnell)I flew to Juba and then on to Bentiu. At this time of year, from 25,000-feet, South Sudan is all lush emptiness, the swamps prodigiously watered by rain and river. The unbroken green was only disrupted as the plane descended, banking over a town-sized rectangle of white-roofed buildings carved out of the wilderness.

The UN twin-prop I flew in landed on a dirt runway outside Bentiu. At one end government soldiers unloaded unmarked crates from a military-chartered Antonov 26. Three Land Cruiser pickups fitted with heavy machine guns–one with a garland of pink plastic flowers on the radiator grille–idled nearby.

The drive to the UN peacekeeping base was short. Since the start of the war six UN bases have become refuges for tens of thousands of people, uprooted by conflict, but only one of these–Bentiu–has become a city.

A UN base outside Bentiu. (AFP / Tristan McConnell)

A UN base outside Bentiu. (AFP / Tristan McConnell)There were 118,000 people living in the base when I arrived, with thousands more arriving each week, despite the recent signing of a peace deal that has so far not brought peace. For its residents, the UN base meant safety above all else because peacekeepers from Ghana and Mongolia manned the watchtowers and patrolled the perimeter.

I went to the area close to the camp’s southern gate where I’d been told I would find the newly-arrived. On the way, an economics student whose studies had been disrupted by the war agreed to translate for me.

Approaching one of the tents where families live crammed together in the stifling heat I explained I was a journalist interested in how people had been affected by the conflict. I asked if anyone would be willing to talk to me. The camp’s residents are overwhelmingly women and children, and the first woman I spoke to agreed to share her story.

It was horrific.

Young women carry firewood at a UN base. (AFP / Tristan McConnell)

Young women carry firewood at a UN base. (AFP / Tristan McConnell)She said when the army and its allied tribal militia attacked her village she saw seven men killed. Two were burned alive in their huts and five were shot, including her brother-in-law. From her hiding place in the bush she saw the women attacked too.

“Ladies with young children, who couldn’t run away, were raped by different men. They raped the married ones and they took away the girls,” she said.

“How many did they take?” I asked.

“I knew four of them,” she said. “One was 18, two were 15 and one was 12.”

A woman walks with her cousin, son and another boy at the UN base. (AFP / Tristan McConnell)

A woman walks with her cousin, son and another boy at the UN base. (AFP / Tristan McConnell)She said the sister of one of the abducted girls was living nearby and she could take me to see her.

In the next tent I found two sisters who had lost six daughters between them. They had watched from the swamp as armed men marched them away.

In another shelter were another two sisters–aged 28 and 15–who had both been abducted and gang-raped. There was a mother raped with her 12-year old daughter and another held for two months, separated from her five children, including her youngest who was still breastfeeding.

A group of women and children in Unity State in June 2011. (AFP / PHIL MOORE)

A group of women and children in Unity State in June 2011. (AFP / PHIL MOORE)And so it went on: every shelter I stopped at had its own horror story but the similarities between them pointed to something systematic, organised, planned. During six days in Bentiu I conducted dozens of interviews with women and girls who had been abducted and escaped or were recounting the experience of their children or sisters or mothers. Gradually I built up a picture of the abuse.

Numerous women talked of encampments where women were tied up or held under armed guard during the day, then gang-raped by queues of men at night. “Rape camps” seemed the only appropriate description.

A South Sudan government soldier. (AFP / Samir Bol)

A South Sudan government soldier. (AFP / Samir Bol)What will happen now that this story has come out? Perhaps it will end up just a footnote to the litany of horrors perpetrated during this latest spasm of violence in South Sudan, destined to be ignored and then forgotten.

But I hope not. As part of the current peace deal a “hybrid” war crimes court is to be established–involving both South Sudanese and international judges–along the lines of the international criminal tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, or the Special Court for Sierra Leone, all of which have seen senior political and military figures tried, sentenced and jailed.

If reconciliation is to be more than enforced forgetfulness and if peace is to be lasting, then there must be justice for the crimes committed in South Sudan. The rape camps of Unity State should be high on the prosecutors’ list.

Names of the women in this blog have been changed to protect the identity of the victims.

Tristan McConnell is an AFP correspondent based in Nairobi. You can follow him on Twitter @t_mcconnell

A victim of sexual abuse tells her story in the Sudanese capital in March. (AFP / Ashraf Shazly)

A victim of sexual abuse tells her story in the Sudanese capital in March. (AFP / Ashraf Shazly)