Chasing Fidel's ashes

Havana -- I spent a nerve-wracking week chasing Fidel Castro’s ashes, criss-crossing Cuba with my colleagues, from Havana to the other side of the island, in a reverse retracing of his momentous 1959 journey that marked his coming to power.

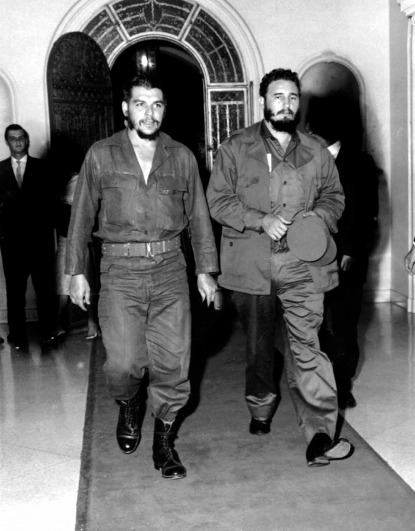

Ernesto Che Guevara (L) and Fidel Castro (R) in Havana's famous 1830 restaurant four years after he and Fidel Castro led the revolution that toppled Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista. (AFP / files-Consejo Estado/Ho)

Ernesto Che Guevara (L) and Fidel Castro (R) in Havana's famous 1830 restaurant four years after he and Fidel Castro led the revolution that toppled Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista. (AFP / files-Consejo Estado/Ho)The 900-kilometer route that he took back then, the so-called “Caravan of Freedom,” produced those famous images of Fidel and Che Guevara on the back of a truck, entering Havana triumphantly amid jubilant crowds.

Our trip ended up being much longer than Fidel’s, then or now, as we bumped along back roads, doubled up, wasted hours stuck at roadblocks or simply getting lost.

Like other major news outlets, AFP had spent decades preparing for Castro’s death and put in an ambitious plan to cover the laying to rest of the “Father of the Nation.”

Five photo-video teams and three text journalists were dispatched to document the convoy carrying Fidel’s ashes through different towns and cities. We would do it partly in relay, one team covering the first city, then rushing to the third, while another team covered the second stop, and so on. It was also a risky plan. Roads were closed ahead of and behind the cortege. If you got stuck, you were delayed for hours and missed the next stop.

Sending out our images posed a further logistical challenge. We usually file our material via the internet, which is quite restricted in Cuba. Another way is to bring your own satellite, but that engenders prohibitively high import taxes. Your only way to go online is public wifi hotspots that you access with prepaid cards, but these have dubious connection strengths. Not having internet was more challenging than I expected. You lose track of the outside world or the days of the week.

The chase started early on a Wednesday, when the convoy of about a dozen cars accompanying the cortege carrying the ashes drove down Havana’s picturesque seaside Malecon Avenue.

A helicopter following the motorcade became a far-off indicator of the caravan’s progress. The cortege was simple enough: a brown cedar urn holding the ashes mounted among white roses on the back of an open-bed green jeep and covered with a glass case. On the back of the urn were the words ‘Fidel Castro Ruz’.

(AFP / Yamil Lage)

(AFP / Yamil Lage)The convoy drove faster than expected and you had to plan your shot carefully to get the casket in those 10 seconds it was in sight (and pray no one jumps into your frame at the last minute). People lined the streets, cheering and waving, a sea of Cuban flags. The same scene replayed itself in towns and cities all along the route. At every site loudspeakers played the teary tune “Su nombre es pueblo” (“His name is people”), an ode to the fighters who died for the fatherland, by diva Sara Gonzalez, a sort of Cuban Edith Piaf.

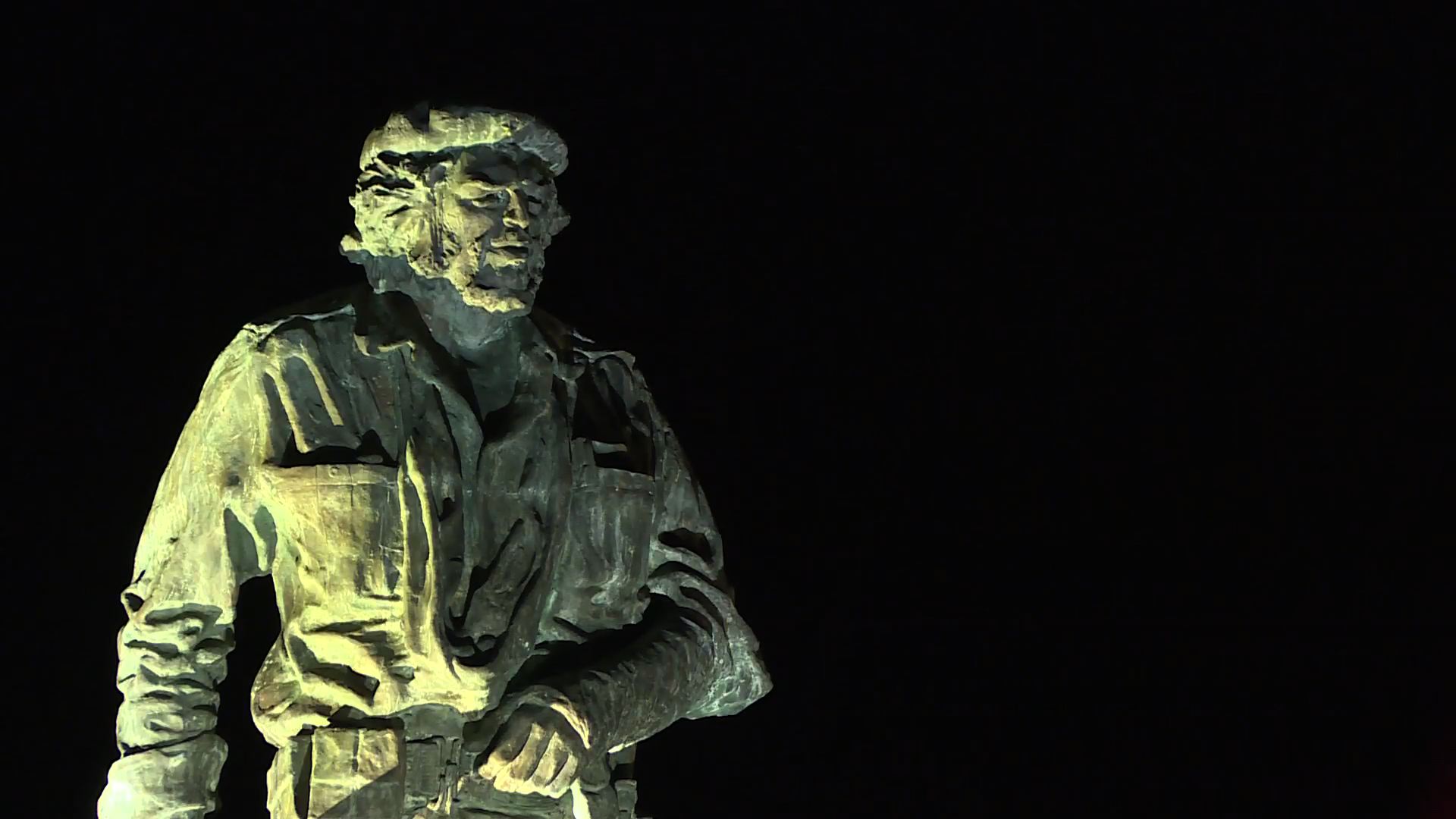

One highlight was the cortege passing by the memorial to communist fighter Che Guevara in Santa Clara. Thousands of people waited for hours, pressing forward when Fidel’s convoy passed the mausoleum with its life-sized statue of the wavy-haired revolutionary in the midnight hours. His ashes spent the night alongside the remains of his former comrade, united one last time.

Our driver, Carlos, was a local with a sharp sense of humour and a questionable sense of direction. He also had the tendency to swerve in front of oncoming traffic, often to avoid giant potholes in the road. At one point he got a mouthful from a hapless policeman who almost drove into us. We got lost every night on the way to our accommodation. Road indications are few and far between in Cuba, so the practice is to pull up next to a local and simply shout your destination. They then point you in the (hopefully) right direction.

Moving an elaborate funeral cortege across a country takes some organising. We were stuck a lot at road blocks either to clear the road ahead of Fidel, or to allow the passage of massive motorcades of buses and trucks transporting locals to where the cortege would pass. Usually known for being difficult, the police generally were quite helpful, especially after seeing our press credentials. When one insisted on blocking us, we snuck by along a back road.

People follow the convoy transporting the urn with the ashes of Cuban leader Fidel Castro through the streets of Las Tunas, Cuba, on December 2, 2016. (AFP / Ronaldo Schemidt)

People follow the convoy transporting the urn with the ashes of Cuban leader Fidel Castro through the streets of Las Tunas, Cuba, on December 2, 2016. (AFP / Ronaldo Schemidt)Another time we convinced the authorities to let us drive through Fidel’s guard of honour all the way to the wifi hotspot. The hotspot happened to be in the very square where the ashes were to make a brief stop, which meant droves of inquisitive stares of townspeople as we passed. I filed my video just in time to grab my camera and film the cortege pulling in. There were a few times like that, when Fidel’s ashes ended up chasing us.

The nights were long and sleep was short. The chase left us little time to explore the country at leisure, and official mourning rules banned live music and alcohol sales, which meant two of Cuba’s most famous exports were off bounds.

Billboards eulogising Castro were ubiquitous. He may have said he didn’t want statues in his name or institutions named after him, but the personality cult largely made up for it.

High school students wait for Castro's ashes to be driven by them in Santa Clara, December 1, 2016.

(AFP / Ronaldo Schemidt)

High school students wait for Castro's ashes to be driven by them in Santa Clara, December 1, 2016.

(AFP / Ronaldo Schemidt)“Yo soy Fidel” (“I am Fidel”), or simply “Fidel” adorned walls and buildings, often in fresh paint. Made me wonder just how present revolutionary discourse was in people’s lives.

(AFP / Ronaldo Schemidt)

(AFP / Ronaldo Schemidt) (AFP / Pedro Pardo)

(AFP / Pedro Pardo)

Fidel Castro had a spotted legacy -- some considered him a savior and champion of the poor, some considered him a dictator who crushed the opposition. Among the Cubans who came out to watch his last voyage across the island, I saw a celebration of a man who largely defined their identity over five decades. The sadness that I saw was raw and real, like young soldiers sobbing as the cortege passed by.

A soldier is comforted after Castro's ashes are driven through Santa Clara on December 1, 2016.

(AFP / Ronaldo Schemidt)

A soldier is comforted after Castro's ashes are driven through Santa Clara on December 1, 2016.

(AFP / Ronaldo Schemidt)Our various teams converged in the eastern city of Santiago for Fidel’s last mile: his arrival, stops at key points where his revolution started in 1953, and finally the burial. We were told we’d receive a live public television feed of the ceremony. Fifteen minutes before the start that plan was cancelled. “This is Cuba,” we told our bosses in Paris.

Later images showed Raul Castro lifting the urn with his brother’s remains into a large stone crypt, and soldiers fixing a metal plaque over the opening, with the simple inscription: Fidel.

Fidel Castro's tomb in Santiago.

(AFP / Yamil Lage)

Fidel Castro's tomb in Santiago.

(AFP / Yamil Lage)Fidel’s journey had ended, but we still had a 16-hour drive back to Havana to catch our various flights home. Our race had given us a glimpse into a nation saying farewell to the only leader that many of them had ever known. At times the chase was impossibly stressful, but there was also the thrill of witnessing history. Years from now I will look back and proudly say, I was there.