Death of a legend

Havana -- The call for which the the bureau had spent decades preparing came around midnight. “Fidel is dead, Raul just announced it on television,” Adalberto “Roque” Velazquez, a photographer and a pillar of AFP’s Havana operation, said hurriedly. Then he hung up.

Raul Castro announces his brother's death on television (AFP / Cuba television)

Raul Castro announces his brother's death on television (AFP / Cuba television)Before I took up the helm of the bureau a few years ago, I was told that I would no doubt end up covering the death of Cuba's legendary leader Fidel Castro. But I didn't really think I would. Some dozen bureau chiefs before me had been told the same thing. But it never happened. The guy just kept living.

Fidel Castro meets Pope Francis in Havana, September, 2015.

(AFP / HO/Cubadebate.cu)

Fidel Castro meets Pope Francis in Havana, September, 2015.

(AFP / HO/Cubadebate.cu)Castro’s death is a big thing and you don’t want to be the agency to get it wrong.

As soon as Roque hung up, I turned on the radio, the television, opened up all the usual social media websites on my computer. Silence. Not a word about Castro dying. What is this? I ask myself. Castro is dead and noone is talking about it? I start to have doubts. I call back Roque, who has gotten into his car.

-- I don’t see anything anywhere, are you sure about what you heard?

-- Yes, I recorded it.

-- Can you play it for me?

-- Sure, when I get to the bureau.

-- When will that be?

-- In about a half hour.

Fidel Castro in Argentina in 2006.

Fidel Castro in Argentina in 2006.Half hours is an eternity, we can’t wait that long.

I ask him to turn around, go back home and play his recording back to me, which he for technical reasons can't do while in his car. As I wait for his call, I ring my deputy, Hector Velasquo. He didn’t see Raul Castro on television. But he got a call from another bureau oldtimer, Rigoberto “Rigo” Diaz, whose wife saw the announcement. I feel a bit better, but I want to hear it for myself before unleashing the news on the world, especially since the government media are still mum on the subject and there is still nothing on social networks. (It would take the communist daily Granma five hours to put up the news on its website).

Some agonizing minutes later, Roque calls again and plays back the recording for me. Sure thing, it's Raul saying his brother has died.

I send a “flash,” meaning news of the highest priority, which bypasses all the other stories that may be waiting in their electronic queue.

“Fidel Castro dies - Raul Castro”

It is 12:16 am in Cuba. In the end, we appeared to be the first international news outfit to give the news.

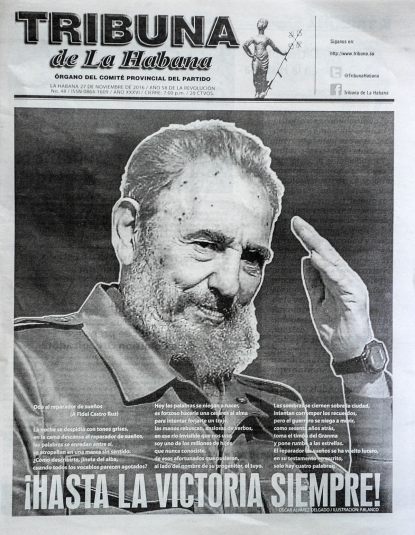

Cuba's Tribuna de la Habana. "Until victory forever, Fidel!" November 27, 2016.

(AFP / Yamil Lage)

Cuba's Tribuna de la Habana. "Until victory forever, Fidel!" November 27, 2016.

(AFP / Yamil Lage)Usually we put our initials on all copy. But with the adrenaline pumping, I forgot to put mine on the flash. The copy editor on the desk in Paris did the usual in these circumstances and put “bur,” short for “bureau.” In the end that was the most appropriate. I may have been the one for write the flash, but it was years and years in the making, both by the locals in the bureau, expats who preceded me and staff at headquarters.

News agencies prepare for a momentous event like this years ahead of time -- numerous stories are written and carefully updated through the years, photos and videos are carefully selected, graphics are put together. When the big moment comes, we can send all of this quickly to clients. But there is still a mound of work to do.

I hurry to the bureau, taking advantage of the half hour en route to call a few diplomats to give them the news. The streets of Havana are quiet, few people seem aware of the news. It’s still early.

Reading the news in Havana on November 26, 2016.

(AFP / Yamil Lage)

Reading the news in Havana on November 26, 2016.

(AFP / Yamil Lage)The bureau fills up quickly and we all get to work. It’s an awesome sight to see mobilization like that, especially since I sense that my Cuban colleagues are moved. The thing that has surprised them the most is the manner in which the government has chosen to announce the news, for which it surely must also have spent years preparing. It seems so abrupt. And with no follow-up. Raul Castro’s announcement lasted for barely a minute, ending with elder Castro’s signature battle cry, “Until victory, always!”

Fidel Castro had been in ailing health for a long time, but there were no hints of late that the end was near. With hindsight, maybe we did have a bit of an indication the week before he died, because one day he met with Vietnam President Tran Dai Quang, but the next didn’t receive Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, despite the fact that he had had warm relations with Trudeau’s father, Pierre-Elliott Trudeau.

Fidel Castro in his epic 4:29-hour speech at the UN, September, 1960. (AFP / Oah)

Fidel Castro in his epic 4:29-hour speech at the UN, September, 1960. (AFP / Oah) Delivering a less lengthy May Day speech in Havana, May, 2004.

(AFP / Niurka Barroso)

Delivering a less lengthy May Day speech in Havana, May, 2004.

(AFP / Niurka Barroso)

The bureau worked nearly non-stop for the first 24 hours after his death (reactions, updating the main stories, writing relevant sidebars) and we knew that we won’t get much sleep during the upcoming week.

The agency sent reinforcements -- reporters, photographers, videographers, who are a big help, but also additional work, as they all require accreditation, lodging. Cuba is not a place where you can come as a journalist and just hit the ground running, there is a whole cycle of formalities to go through first.

Working as part of a large team like this is truly a pleasure. In the end, I am very lucky, professionally speaking -- not only did I get to cover Cuba’s rapproachment with the US, but also the death of its larger-than-life leader. As we worked during those first few days, I thought of all of my predecessors. All of our output is thanks to them, as well.

This blog was written with Pierre Celerier and translated by Yana Dlugy in Paris.

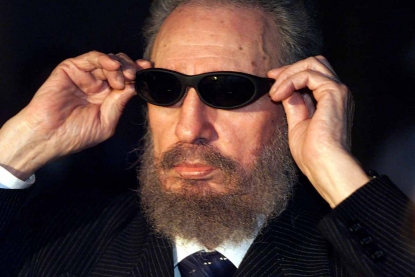

Gazing into the bright future in Havana, November, 1999.

(AFP / Christophe Simon)

Gazing into the bright future in Havana, November, 1999.

(AFP / Christophe Simon)