In Cuba... at last

Havana, November 4, 2015 -- I first booked my tickets to Havana 15 years ago.

I was a 20-year-old American college student, and my old high school Spanish teacher, a glamorous Argentine woman married to a UN diplomat, had invited me to visit them in Cuba, where her husband had just begun a new post.

A Ford Fairlane 57 passes near the Capitol in Havana in February, 2008. (AFP / Luis Acosta)

A Ford Fairlane 57 passes near the Capitol in Havana in February, 2008. (AFP / Luis Acosta)She had lived all over the world before landing in Muncie, Indiana, the small town where I went to high school, and where her husband had a professorship at the local university.

She had made it her mission to introduce her sheltered Midwestern students to the worlds of art, ideas and travel, and quickly became my favorite teacher.

We had kept in touch since I graduated, and when she invited me to visit Cuba, I thought: "This is the coolest thing ever."

I was fascinated by the sickle-shaped island just off the Florida coast, which had all the allure of a forbidden land -- its seaside boulevards, classic American cars and crumbling colonial buildings just out of reach under the US embargo.

Havana, 2011. (AFP / Adalberto Roque)

Havana, 2011. (AFP / Adalberto Roque)I bought a ticket to Havana via Kingston, Jamaica, the easiest route I could find to circumvent the travel ban.

But then my teacher called to say she had to cancel.

It was the summer of Elian Gonzalez, the five-year-old Cuban boy who had been found floating in an inner tube after the boat carrying him, his mother and 12 other asylum seekers sank in the Florida Straits.

His relatives in Miami wanted to keep him. His father in Cuba wanted him back. Both governments got involved and a mess of monumental proportions ensued.

Then six-year-old Elian Gonzalez at his Miami relatives' house in April, 2000. (AFP / Meredith Davenport)

Then six-year-old Elian Gonzalez at his Miami relatives' house in April, 2000. (AFP / Meredith Davenport)My teacher told me her husband had been receiving death threats -- probably from a Cuban exile group, she said -- after publicly calling for little Elian to be returned to his father.

They had decided to leave Cuba until things settled down.

I still could have gone to Havana on my own, but the thrill of the idea had suddenly turned scary.

I didn't have much travel experience. Tensions between the two countries were spiraling. And the penalties I could face for breaking the embargo suddenly seemed a lot more dire: up to 10 years in prison and $50,000 in fines, under the Trading With the Enemy Act.

I chickened out.

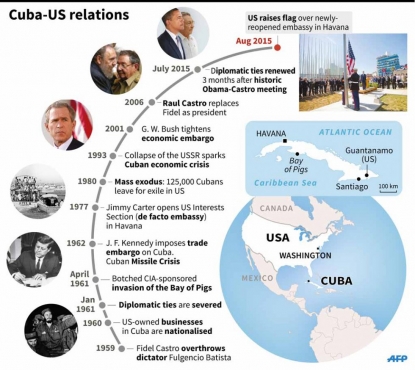

(AFP Graphics)

(AFP Graphics)Fifteen years later, I now work as a foreign correspondent for AFP. I'm based at our Latin American headquarters in Montevideo and have traveled all over the world on assignment.

But I never did manage to get to Cuba -- until Pope Francis announced his trip there, and my boss asked me to cover it.

I suddenly felt 20 again. "Coolest assignment ever," I thought.

Havana, ahead of Pope Francis's visit, August, 2015. (AFP / Yamil Lage)

Havana, ahead of Pope Francis's visit, August, 2015. (AFP / Yamil Lage)This time, my trip would be legal. Journalists are one of the 12 categories of travelers the US authorizes to visit Cuba.

I was so excited to fulfill my dream deferred that I decided to bring my wife and eight-month-old daughter with me.

My wife is French, and my daughter can take her pick between her French, Uruguayan and American passports -- so they didn't have to worry about the embargo.

We did, however, have to worry about baby gear. The AFP bureau chief in Havana, Alexandre Grosbois, and his wife told us it was often impossible to find diapers, baby wipes, baby food or baby just-about-anything in Cuba.

Havana, January, 2015. (AFP / Yamil Lage)

Havana, January, 2015. (AFP / Yamil Lage)We would have to bring every bit of baby stuff we'd need for two weeks -- a logistically daunting task.

My wife would also be stuck taking care of the baby by herself for most of the first week, when I would be off covering the pope.

Making me fall in love with her all over again, she agreed to this crazy plan.

We got a guide book, reserved a rental car and started mapping out a road trip around the island for after the pope's visit. (A note to the US Treasury Department: This was for journalistic purposes, not a vacation. Please don't put me in jail or fine me.)

Havana, January, 2007. (AFP / stringer)

Havana, January, 2007. (AFP / stringer)To get my journalist visa, I had to go through a screening process at the Cuban embassy -- two meetings with an official who looked very cold in the Uruguayan winter and was, I guess, tasked with vetting me to see if I worked for the CIA.

I must not have raised much suspicion, because his questions were benign. He spent most of the time giving me travel tips.

In fact, everyone at the embassy was extremely nice and eager to give me advice on where to go, what to do and how to keep the baby cool in the tropical heat.

Flooding in Havana after heavy rains, April, 2015. (AFP / Yamil Lage)

Flooding in Havana after heavy rains, April, 2015. (AFP / Yamil Lage)We got an even warmer reception when we arrived.

Taxi drivers, waiters, market vendors and random strangers were thrilled to meet an American and talk about our nations' nascent reconciliation -- brokered in part by the visiting pope.

"There was never any problem between the Cuban people and the American people. It's a problem between our governments," said a taxi driver who took me to the office one morning in a gorgeous turquoise 1957 Chevy Bel Air.

Countless other Cubans took me aside to tell me similar things.

Santiago de Cuba, January, 2007. (AFP / Adalberto Roque)

Santiago de Cuba, January, 2007. (AFP / Adalberto Roque)But if people were interested in me, they were absolutely gaga over my baby.

Cubans may love babies more than anywhere I've ever been. Our cute blonde daughter was a superstar everywhere she went.

If anyone out there has young kids and is looking for a vacation spot, Cuba is your destination.

In the "casas particulares" where we stayed -- essentially family-run B&Bs, one of the budding forms of private enterprise the communist regime has begun allowing in recent years -- our hosts delighted in playing with our daughter, cuddling her and feeding her.

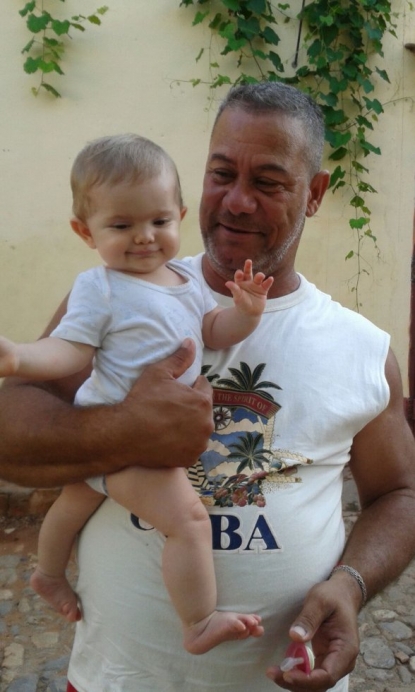

B&B owner in Trinidad holds author's baby, September, 2015. (Photo courtesy of Celia Schlanser)

At restaurants, waiters and waitresses would bend down to coo at her and end up picking her up and taking care of her for the rest of the evening -- leaving us to enjoy our first romantic dinners in months.

Our daughter loved the attention, and seemed to love Cuba, too. She was smiling and happy throughout the trip, despite the long days and the heat.

We have a hilarious video of her rocking out to Cuban beats one day in her stroller, and she came back with no less than three sets of maracas -- gifts from her admirers that are now among her favorite toys.

Like the other American travelers we met -- and there are plenty, both legal and illegal -- I'm a little hesitant to advertise the island's charms.

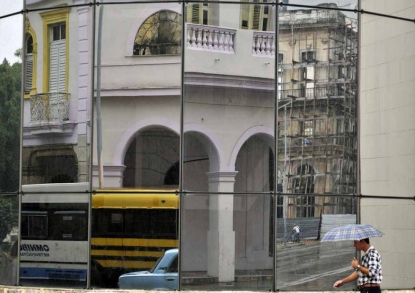

Old Havana, November, 2008. (AFP / stringer)

Old Havana, November, 2008. (AFP / stringer)In the words of one American I interviewed, a Catholic man who came down for the pope's visit on a charter flight organized by the Miami archdiocese, "things will start changing (when) the cruise ships start coming."

There is a fear that Cuba, one of the last places on Earth that American consumer culture has not reached, will become just another touristy Caribbean island when the embargo is lifted.

A cruise arrives in Havana's harbor, 2006. (AFP / Adalberto Roque)

A cruise arrives in Havana's harbor, 2006. (AFP / Adalberto Roque)I admit I was fascinated by Cuba in part because it was so close yet so very far from the United States.

I grew up in the 1980s, in an America that was still very much fighting the Cold War. I didn't live through the worst in US-Cuban relations, but my parents did, and had told me stories about holding drills at school to prepare for a nuclear attack in the wake of the Cuban Missile Crisis.

My mom's running joke is that the drill was, "Bend over, put your head between your legs and kiss your sweet ass goodbye."

To my generation, though, this was all a little fuzzy. We knew the Soviet bloc was the enemy, and communism was evil... but why?

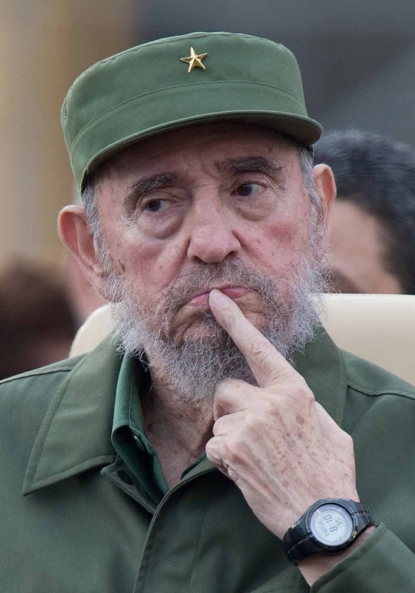

Former president Fidel Castro is pictured in Havana in September 2010. (AFP / Adalberto Roque)

Former president Fidel Castro is pictured in Havana in September 2010. (AFP / Adalberto Roque)As I reached the questioning age of adolescence, I wanted to know what this communism business was really all about.

That curiosity about the "otherness" of Cuba still lingered after all these years.

I had so many questions about life on this island that seemed the antithesis of America.

A gallery in Trinidad, September, 2015. (Photo courtesy of Celia Schlanser)

Questions like, What kind of dish soap do they have? (Vietnamese, it turns out.) What's their toilet paper like? (Basically like ours, but thinner and unperforated -- at least the specimens I saw.) Is there a local equivalent of McDonald's? (Pretty much, but the burgers we ordered turned out to be a slab of pork between two buns -- no lettuce, no tomato, no special sauce.) Do they have any American products at all? (Tons, from the ubiquitous Cokes to the latest "Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles" movie, which was on the cinema marquees.)

On a less frivolous note, I simply wanted to know what it was like to live under communism.

A Cuban and her cigar. Havana, February 2008. (AFP / Luis Acosta)

A Cuban and her cigar. Havana, February 2008. (AFP / Luis Acosta)My romantic 20-year-old self would maybe be a little disappointed to know that the answer I came away with was: not very nice.

First, there was the issue of equality.

My 20-year-old self imagined Cuba as an egalitarian utopia. But the first thing you notice as a foreigner is that there are two separate economies, with separate money.

Foreigners and the Cuban elite use the Cuban Convertible Peso, or CUC.

Roughly equivalent to the dollar, it is the currency of restaurants, hotels and high-end stores.

But ordinary Cubans have no systematic access to it. They live in a far more restricted economy, that of the ordinary peso.

Cubans rest on a bench in downtown Havana in January, 2007. (AFP / Juan Carlos Borjas)

Cubans rest on a bench in downtown Havana in January, 2007. (AFP / Juan Carlos Borjas)Then there was the issue of government repression, which felt to me as heavy and omnipresent as the tropical humidity.

Even as visitors, we were constantly aware of being watched by the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDRs), which are basically people who spy on their neighbors for the Castro regime.

The first thing we had to do when we arrived at a new B&B was give our passports to the owners so they could report our arrival to the CDR.

This was both a way to keep an eye on us and to prevent the owners from trying to take any payment under the table in order to dodge the enormous taxes charged by the government.

Slogans for the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDRs) painted on a wall in Havana. (AFP / stringer)

Slogans for the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDRs) painted on a wall in Havana. (AFP / stringer)People we met described the CDRs' pervasive presence in Cuban life.

A Cuban journalist, who was gay, told me about living in fear in the years of Fidel Castro's homophobic crackdowns.

"If the local CDR guy found out you were gay, you could lose everything. You'd never work again. Same thing if they found out you had relatives who had left for Miami," he said.

Cubans recall the repressions of the Fidel regime in the 1960s and 1970s.

Click here to watch on a mobile device.

The regime definitely has its defenders, including the owner of the first B&B we stayed in -- a lovely woman named Julia who had worked in counter-intelligence and joked with me about all the times they'd had to disrupt American plots to assassinate her boss, Fidel.

Julia, who had a spacious apartment just up the street from a famous Havana hotel, the Hotel Nacional, praised the government's gains in health, education and equality.

"When I was a little girl, poor kids like me, or black kids, couldn't even come to this neighborhood," she told us.

All of which was true.

Havana, September, 2013. (AFP/Yamil Lage)

But Cubans who didn't work in counter-intelligence and weren't personal acquaintances of the Castro family tended to be more critical.

Still, there's something beautiful about the Cuban way of life.

With their seemingly magical ability to keep their classic cars running, their beat-up appliances humming and their crumbling colonial buildings standing, Cubans show that there's an alternative to what Pope Francis calls the "throwaway culture."

Sadly, though, Cubans don't live like this because they want to -- they do it because they don't have a choice.

If not for half a century of isolation by the United States, they would have junked those iconic '50s Chevies decades ago, just like Americans did.

A Cuban fixes his 1954 Chevrolet in Havana in May, 2007. (AFP / Rodrigo Arangua)

A Cuban fixes his 1954 Chevrolet in Havana in May, 2007. (AFP / Rodrigo Arangua)I imagine the island is going to change fast in the coming years.

I'm holding out hope that most of the changes will be for the better.

Hopefully I'll get to go back someday and see how it unfolds.

I'd love to return with my daughter and tell her what it was like when she was a baby.

Maybe next time she can even travel on her American passport.

Joshua Howat Berger is an AFP correspondent based in Montevideo.

Havana, February 2008. (AFP / Luis Acosta)

Havana, February 2008. (AFP / Luis Acosta)