Post-hurricane Haiti, unfiltered

Port-au-Prince -- As I made my way through Haiti in the wake of Hurricane Matthew, which killed hundreds and devastated parts of the impoverished island, I aimed to show exactly what I saw, without any filter of distance. You can’t but feel the grief, anger and pain when you see scenes like this, when a natural catastrophe takes away from those who already have so little in this world.

Aftermath of Matthew in Les Cayes.

(AFP / Hector Retamal)

Aftermath of Matthew in Les Cayes.

(AFP / Hector Retamal)Because of bad communications, it took some time to learn the scope of the death and devastation that Matthew left behind after it ripped through the island on the night of October 3-4. Initial reports on the 4th, after the hurricane left Haiti and headed for Cuba, said that less than a dozen people had been killed. On the 6th, the death toll rose to 108. A few days later, it would be over 500 dead.

Because we know ahead of time that a hurricane will strike, we have time to prepare for coverage. When we learned, about a week before, that Matthew would make landfall in Haiti, we began to stock up on essential equipment, like batteries and provisions. But we never imagined just how intense the storm would be and just how devastating.

Covering a hurricane begins long before and ends long after it passes. Two days before it slammed into the island, as it still churned in the Caribbean, we drove around the capital Port-au-Prince to see how people were preparing for the storm. We found that many did not even know that a powerful hurricane -- Matthew would smash into Haiti as a Category Four storm, on a scale of five -- was headed their way. The fishermen of the impoverished Jeremie Wharf, knew. They didn’t go out to sea for a few days prior.

Playing football in Leogane ahead of the storm.

(AFP / Hector Retamal)

Playing football in Leogane ahead of the storm.

(AFP / Hector Retamal)A few hours before Matthew was supposed to hit, my colleague Amelie and I went to Leogane, a region southwest of the capital.

There is a small village there, next to the beach. The first raindrops had started to fall and the wind had started to strengthen. Near the beach, people were listening to music next to their fishing boats and children were playing ball. They all thought that the storm would pass, like others before it.

We passed the night of 3-4 October, as Matthew passed over Haiti, trying to learn what was happening in the southwest of the country, where the storm first made landfall and the area that logically would be expected to be the worst-affected. After a few hours of sleep, we eventually went out to see what the situation was in Port-au-Prince. We found people making their way through flooded streets. It was nothing compared to what eventually greeted us in the southwest.

Port-au-Prince after Matthew had passed.

(AFP / Hector Retamal)

Port-au-Prince after Matthew had passed.

(AFP / Hector Retamal)Our immediate goal was to try and reach Les Cayes, the area that was reported to be the worst-hit. The road was cut by the flooded Digue river. People were passing it on foot or paying 50 gourdes (around 70 euro cents) to be carried across, piggy-back style. We waited to cross in our 4x4, after backhoes cleared the way, after the trucks and the busses.

Crossing a river southwest of Port-au-Prince two days after the storm.

(AFP / Hector Retamal)

Crossing a river southwest of Port-au-Prince two days after the storm.

(AFP / Hector Retamal)As we drove along, we saw many damaged houses, vegetation and plantations. Damaged, but nothing too dramatic. And then, when we reached the outskirts of Les Cayes, the true impact of the storm hit us.

Many people literally didn’t have anything. They were reaching out their arms, asking for help, asking for food. The little that they had was lost in the storm. I can’t tell you how sad it was to see them, the children standing in water in front of their inundated houses, the people crossing rivers to reach their meager dwellings.

Keeping your distance at times like these is impossible. At least for me. I can’t keep my distance from these people. Quite the opposite, I want to show their situation as plainly as possible. I often ask myself if I’m doing the right thing by photographing people in such distress. And each time, I come to the same conclusion -- that it is the only thing to do, to show it all as it is.

In front of what used to be a home in the village of Casanette.

(AFP / Hector Retamal)

In front of what used to be a home in the village of Casanette.

(AFP / Hector Retamal)I also can’t stay impassioned in such situations. Often I leave by hugging the people I have photographed. Or I come back the following day to see how they are faring. All the emotions that go through me in situations like these, I can convey them through my work. Not only can I do so, it is my obligation to do so, to show what is happening on the ground.

Take Leogane for example, that little village outside of Port-au-Prince where the people were listening to music and children were playing ball, thinking that the storm would pass. I went back there. The road was blocked by the flooded river, The Rouyonne. I headed upstream.

People try to cross the La Rouyonne river Leogane after the storm.

(AFP / Hector Retamal)

People try to cross the La Rouyonne river Leogane after the storm.

(AFP / Hector Retamal)I met Jonnathan, a child who had gone to get some water to help his mother clean the house, full of mud.

Jonnathan fetches clean water for his mother in Leogane.

(AFP / Hector Retamal)

Jonnathan fetches clean water for his mother in Leogane.

(AFP / Hector Retamal)Nearby I saw Franki, alone, with his bare feet in the cold water, with a drenched shirt on his back.

Franki stands in his flooded home. (AFP / Hector Retamal)

Franki stands in his flooded home. (AFP / Hector Retamal)I asked myself if anyone in the world was interested in what happened to these children.

At Les Cayes, in the south, lots of people complained that noone has come to help them. Many of them had lost everything. Before, they had little shacks. Now, they had nothing.

We tried to reach the region of Les Anglais, further to the west, where the eye of the hurricane passed. We came across a little fishing village, destroyed by the waves, the wind and the rain. The scenery was that of devastation, covered by debris from what were once houses and trees. None of the houses here escaped unscathed, most of them completely destroyed. There were very few that were built to resist the power of a hurricane. Many of the people there tried to scavenge bits here and there from the destruction, to try and construct some kind of shelter.

Les Cayes after the storm. (AFP / Hector Retamal)

Les Cayes after the storm. (AFP / Hector Retamal)In the evening, I met Reginelson, a young man who offered me coconut milk, the only liquid safe to drink. The only thing remaining of his house were walls and a part of the roof. A man who had lost everything. But still he found it in him to laugh and share the little he had with his visitor. And that, too, I must convey.

Nearly two weeks after the hurricane passed I was in the town of Port-a-Piment, taking pictures of people who caught the cholera that spread after the storm. It was raining heavily. This only added to the general misery -- many of the houses had no roofs and the people inside could not protect themselves from the falling rain.

I met two siblings, 18-year-old Judelin and his 21-year-old sister Judeline. As I approached their house, I saw that Judelin was standing inside, shivering, his eyes gazing around his house, which had been seriously damaged by the hurricane and that was now being drenched by the rain falling through the holes in the roof, like a shower. It didn’t matter whether his sister and he stood outside or inside the house -- water was everywhere. I stayed with them for a long time. I wondered why they weren’t trying to seek shelter elsewhere. Maybe they stayed to try and hand on to the few belongings they had left?

Judeline in her house.

(AFP / Hector Retamal)

Judeline in her house.

(AFP / Hector Retamal) Judelin in his house.

(AFP / Hector Retamal)

Judelin in his house.

(AFP / Hector Retamal)

Today, there are thousands of people like Judelin and Judeline in Haiti. People without proper shelter, without enough food. They stay in their damaged homes and look at the convoys of aid passing them by, without having received any help yet...

This blog was written with Pierre Celerier and translated by Yana Dlugy in Paris.

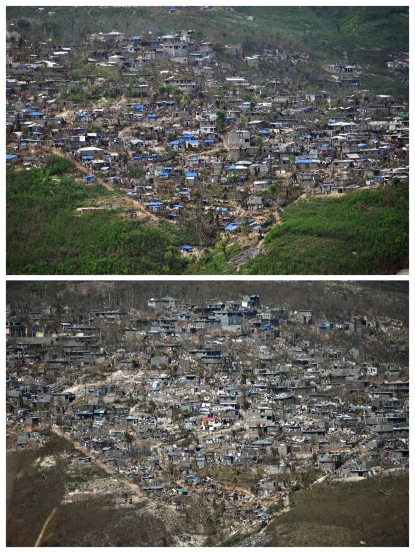

These two pictures show Jeremie, in southwestern Haiti. The top image is on October 22, the bottom on October 10. Many of the houses damanged in the storm have now been covered with tarps and grass.

(AFP / Hector Retamal)

These two pictures show Jeremie, in southwestern Haiti. The top image is on October 22, the bottom on October 10. Many of the houses damanged in the storm have now been covered with tarps and grass.

(AFP / Hector Retamal)