Watching the world burn

As the planet reels from unprecedented heatwaves, floods, wildfires and droughts, you may be feeling a rising sense of unease or even panic.

My own “Oh Shit!” moment came in early 2009, two years after I began writing on the science and geopolitics of climate change for Agence France-Presse. I had reported on scores of peer-reviewed studies, talked to scientists, attended UN climate summits, and interviewed Pacific islanders whose tiny nations were sinking beneath the waves. But the knee-buckling realisation that unchecked global warming would upend civilisation had not yet hit me in the gut and left me gasping for air.

That sucker-punch came at a conference in Oxford where a wide range of experts were asked to imagine a planet that had warmed four degrees Celsius. The tableau that emerged was a waking nightmare. It left me feeling as if I were in possession of terrifying knowledge that others somehow failed to see.

A firefighter tries to prevent a huge forest fire spreading near Louchats in southwestern France on July 17, 2022 (Thibaud Moritz / AFP )

A firefighter tries to prevent a huge forest fire spreading near Louchats in southwestern France on July 17, 2022 (Thibaud Moritz / AFP )Which is odd, because the clear-and-present danger of climate change has been highly visible for a long time. Already in the late 19th century, Svante Arrhenius – the first chemistry Nobel prize winner – predicted that doubling the CO2 in the atmosphere would warm the planet by an unliveable five degrees Celsius. He was not far off. He even speculated on how that might happen: burning too much coal.

In 1969, US presidential advisor and future senator Patrick Moynihan told the Nixon Administration that global warming could lift oceans enough to drown major cities. “Goodbye New York”, he wrote in a memo. “Goodbye Washington, for that matter.” By 1985, astrobiologist Carl Sagan was warning Congress that “we are passing extremely grave problems to our children when the time to solve those problems –if they can be solved at all -- is now.” And in 1988, the same year that US government scientist James Hansen proclaimed that global warming had begun, the United Nations created a corps of volunteer scientists – the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) – to update world leaders on the crisis. Four years later those leaders were sufficiently alarmed to hammer out a treaty to combat “dangerous human interference with the climate system”.

And yet most people seemed blithely oblivious to the killer comet hurtling our way, and saw climate change – if they saw it at all – as an avoidable, future threat. My daily diet of scientific reports and projected impacts made it impossible for me to not look up. As Greta Thunberg says: if you read the science, how can you think about anything else?

Occasionally I would encounter a kindred spirit, someone as quietly freaked out as I about where we are headed. But giving voice to an all-encompassing sense of dread is not something one does in polite company, so I exercised restraint. My one safe space was at home, where – night after night, year after year – I detailed the grim tidings from my beat to my resilient wife. But there was collateral damage. I cringe today when I think about the pall I cast over the lives of my two daughters as they grew into adulthood, especially the youngest.

At work, colleagues berated me for the preponderance of negative stories in my reporting. “We have to give people hope,” said one. “You should focus more on good news.”

Children play on ice melting because of climate change in Alsaka's Yukon Delta on April 18, 2019 (Mark Ralston / AFP )

Children play on ice melting because of climate change in Alsaka's Yukon Delta on April 18, 2019 (Mark Ralston / AFP ) A boy removing oil spilled on Itapuama beach in Cabo de Santo Agostinho, Brazil, on October 21, 2019 (Leo Malafaia / AFP )

A boy removing oil spilled on Itapuama beach in Cabo de Santo Agostinho, Brazil, on October 21, 2019 (Leo Malafaia / AFP )

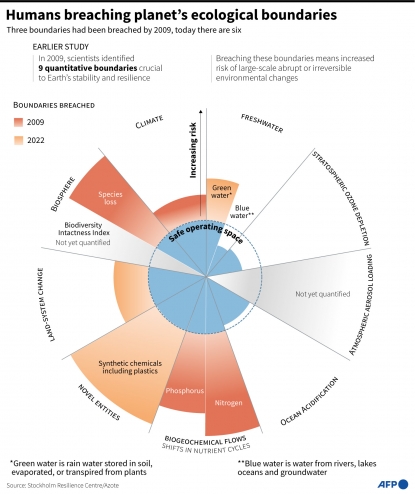

But there is no good news, at least not from nature or science. Since the world collectively decided 30 years ago to fix the climate and save the realm of living things, every indicator of planetary health has dramatically worsened. In 2009 scientists identified nine “planetary boundaries” that must not be crossed. At that time, we had already stepped outside the safe zone of three: global warming, the rate of species extinctions, and too much nitrogen in the environment (mostly from fertiliser). Today we have breached six, probably seven. We are spewing out more greenhouse gases and pollution of all kinds than ever before.

The most common refrains in the thousands of peer-reviewed studies on climate change and environmental degradation I’ve looked at over the last 15 years are “worse than we thought”, “faster than we feared”.

What passes these days as good news is virtue-signalling “net zero” targets – from countries and companies – that depend more on planting trees and dubious carbon offsets than actually reducing emissions. In science, an endless stream of if-we-do-everything-right models chart fantasy pathways to a world in which Earth’s average surface temperature never warms more than 1.5 degrees Celsius above late 19th-century levels. (The mercury has risen 1.2C so far, mostly in the last 50 years.)

These well-intentioned storylines – designed to show leaders and led alike that we can still avoid the worst – are presented as “technically feasible”, which means they work on paper. In the real world of vested interests and political pressure, not so much.

Tellingly, the last year has also seen frothy enthusiasm for engineering solutions – sucking CO2 from the air, dimming solar radiation with stratospheric sunscreens – that were dismissed a decade ago as desperate, last-ditch measures. That may be where we have landed. In its latest report, published earlier this year, the IPCC made it crystal clear there will be no climate salvation without major contributions from these and other technologies still on the drawing board or in their infancy. We’re skating on thinning ice.

A polar bear on melting ice floes in Russia's Franz Josef Land archipelago on August 16, 2021 (Ekaterina Anisimova / AFP )

A polar bear on melting ice floes in Russia's Franz Josef Land archipelago on August 16, 2021 (Ekaterina Anisimova / AFP )

Let’s just say it: the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C cap on warming is a mirage evaporating on the drought-stricken horizon. We will cruise right past it. Does this spell extinction-level doom? Of course not, but how bad things get does depend on how deeply we wander into the hot zone.

Beyond a certain threshold – and no one knows exactly where that is – the planet itself will significantly boost warming and release large stores of carbon that will overwhelm our already belaboured efforts to slow and eventually stop human emissions. In the meantime, we are rapidly destroying Earth’s life-support systems. Oceans, forests and soils are straining to maintain the steady-state conditions that have made this such a hospitable place for our species over the last 11,000 years, and could abruptly change course and race toward a new “hothouse” equilibrium as has happened in the past, warn the big-picture scientists.

That’s not a world we can live in.

With one climate-enhanced disaster after another, reality is beginning to bite hard around the world. Paradoxically, this is, for many, reassuring. With lingering doubts – long fostered by Big Oil – finally extinguished, a climate action Marshall Plan is surely the only rational choice left. Politicians are woke, the markets have awoken. But do they truly grasp that we’ve only seen a faint foretaste of the impacts already baked into the climate system? Even if we start throwing trillions of dollars, euros and yuan at the problem, things are going to get worse – a lot worse – before they get better. And that’s the optimistic scenario.

A young Indian man dangles from a power line after the Ganges River broke its banks near Allahabad in August 2013 (Sanjay Kanojia / AFP )

A young Indian man dangles from a power line after the Ganges River broke its banks near Allahabad in August 2013 (Sanjay Kanojia / AFP )

Nor has it truly sunk in that constructing infrastructure to protect against erratic monsoons, month-long bouts of deadly heat, rising seas, mega-droughts and once-in-a-1,000-year floods is not a viable game plan, not even in countries brimming with money, engineering prowess and can-do confidence.

But the focus of this lamentation is a state of mind more than a state of nature, what it feels like to work what we affectionately call the end-of-the-world beat. How does one carry that burden?

I get that question a lot from my students at the journalism schools in Paris where I teach. Sometimes I shrug it off with a joke – Monday through Friday is for despair, weekends for hope. Or I’ll attempt a serious answer, explaining in general terms how journalists – most famously war correspondents – erect emotional firewalls against the cruelty, suffering and injustice to which they are exposed. AFP photo editors in war-torn regions get trauma training before sorting through pictures with violence too graphic to be published.

For more than a dozen years on the beat, I convinced myself that I was unscathed by the steady drip drip of planetary doom and gloom. My sense of purpose was my shield: helping people understand that failing to repair the damage done will have dire and irreversible consequences. Following the science, my articles inched steadily over the years toward the language of existential crisis, but only rarely did I allow myself to truly contemplate what that meant, to relive the intensity of my original “Oh Shit” moment. When I did, I clenched my teeth until the squall subsided, and carried on.

Now the firewall is crumbling, and I don’t know how to rebuild it.

The firewall is crumbling: Beachgoers watch as a forest fire near Saint Tropez, France, draws closer on July 25, 2017 (Valery Hache / AFP )

The firewall is crumbling: Beachgoers watch as a forest fire near Saint Tropez, France, draws closer on July 25, 2017 (Valery Hache / AFP )

In hindsight, it’s embarrassing how long it took me to connect the dots. Bouts of anxiety, sleepless nights, crippling nerve pain, flashes of anger – I had long attributed them to an unexceptional constellation of money problems, a botched surgery, frustrations at work, and worries about my children. All of those were real, but they were not the only cause.

Squaring off with Covid – and my own mortality – at the pandemic’s outset in early 2020 forced me think hard about life’s Big Questions. I eagerly merged back into the fast lane of daily reporting as soon as I could, but something fundamental had shifted. That same year I was nominated for a newly created international award for environmental journalism that required writing a long essay about why my work mattered. I didn’t win, but the exercise made me realise the extent to which my life had been enveloped by the world’s first permanent breaking story.

I began to consult with a specialist for chronic pain, a former anaesthesiologist who borrows from the psychoanalytic toolbox to help his patients understand the sources of their physical torment. That unlocked some more hidden recesses, but the most obvious trigger remained invisible to me.

The next year I threw my hat into the ring again for the award and won. That came as a pleasant surprise because news agency reporters rarely get the limelight. But it also threw me off balance, for reasons that I still can’t quite grasp. About that time, I started thinking a lot about what it means to live under the lengthening shadow of environmental collapse, much as my generation had cowered as children under our school desks in rehearsals for nuclear Armageddon. But it still didn’t feel personal.

Protesters perform a mock funeral at Glasgow Necropolis to symbolise the failure of the COP26 UN conference in the Scottish city on November 13, 2021 (AFP / Paul Ellis)

Protesters perform a mock funeral at Glasgow Necropolis to symbolise the failure of the COP26 UN conference in the Scottish city on November 13, 2021 (AFP / Paul Ellis) Activists from Extinction Rebellion (XR) hammer home the message that delay will be deadly during COP26 in Glasgow on November 11, 2021 (Andy Buchanan / AFP )

Activists from Extinction Rebellion (XR) hammer home the message that delay will be deadly during COP26 in Glasgow on November 11, 2021 (Andy Buchanan / AFP )

There is a growing literature on the topic, which goes by several names: climate anxiety, eco-anxiety, or in extreme cases, “doomism”. Katharine Hayhoe, a leading climate scientist who travels the US and the world to help people worried about climate change find solace in activism, says the preponderance of her haters on social media has abruptly shifted from climate deniers to doomsayers enraged by her message of optimism and hope.

These so-called doomists have been excoriated by climate scientists and activists who see them as more dangerous than old school climate sceptics. But since these same experts shout from the rooftops that we’re facing an extinction-level crisis, they shouldn’t be surprised if some people lose their shit. If nothing else, it means they’re listening.

Allowing ourselves to be emotionally overwhelmed by the threat of climate change is clearly an indulgence we can’t afford. There’s too much at stake, too little time to act. Which is why folks doing strategic communication on global warming – the UN, green groups, scientists and arguably, the media – tread a very fine line.

They want to scare people enough to take the problem seriously but not so much as to make them feel hopeless. At the same time, they want to reassure people that a climate-secure future is possible but only enough to avoid complacency. I found myself straddling this dilemma when I started teaching a course on climate change. I immediately felt the weight of the students’ expectations. They were like anxious patients fearful of a diagnosis, and I was the doctor telling them to brace for bad news. I half-jokingly issued a trigger warning at the beginning of each semester.

A crack has appeared in the conventional wisdom that a deep dive into climate gloom only makes people give up or tune out. In 2018, I met the founding members of the then nascent Extinction Rebellion (or XR), that used flamboyant acts of civil disobedience to spotlight inaction on global warming. XR has since morphed into a global presence. Induction begins with a crash course in climate science highlighting how we have tipped Earth into a rare period of mass extinction from which humans are not exempt.

That means allowing oneself to be emotionally overwhelmed, and to “grieve” for what has and will be lost. “Today, I see pretty much everything through the lens of climate change,” one member told me. XR adherents, in other words, are not immobilised by their deep sense of foreboding. On the contrary, accepting and embracing our grim future has turned them into an army of implacable climate warriors.

A Brazilian farmer walks through a devastated area of the rainforest near Porto Velho, Rondonia state on August 26, 2019, as wildfires tore through the Amazon region (Carl De Souza / AFP )

A Brazilian farmer walks through a devastated area of the rainforest near Porto Velho, Rondonia state on August 26, 2019, as wildfires tore through the Amazon region (Carl De Souza / AFP )

At a human level, I desperately want to deliver a sanguine vision to my students and people who read my stories, evidence that we can – and will – avoid the worst. But it is not my job – or the job of any journalist – to manufacture hope. To do so would not only be manipulative, but intellectually dishonest.

It may also be self-defeating. Given the urgency I feel about the climate crisis, I yearn to explicitly denounce what I know to be harmful or wrong, and to champion what I think is the right course of action. But acting on this urge, even if it were possible within the strictures of AFP, would be a mistake.

“Reporters actually know more than almost anyone – even most scientists – about the true scale of the threat,” the environmentalist Bill McKibben told me some years ago when I aired my frustration. “But if you become an advocate it will be used to undermine whatever you write,” said the author of “The End of Nature”.

Fair-mindedness, neutrality – and especially the perception of these qualities – are the foundation of our credibility as news organisations.

Our stock-in-trade includes nuanced analysis of why something happened (or may happen), but it does not cross the line from “what is” to “what should be”. More than ever, the world needs fact-based reporting that cannot be disputed, even if it is sometimes ignored or distorted.

I recently interviewed a trio of prominent actors in the climate arena, not realising the extent to which I was subconsciously fishing for advice on how to cope myself. All had grappled with the issues that were slowly causing me to unravel, and each had wisdom to share.

As an Earth system scientist, Johan Rockstrom has helped to reframe understanding of our relationship to the planet. He is also a tireless advocate for climate action, whether he’s bending the ear of global elites in Davos or narrating his Netflix special “Breaking Boundaries”. During a conversation about his signature concept of a “safe operating space” for human activity, I ambushed him with a personal question.

“In 2009, we had transgressed three planetary boundaries, today it’s seven,” I said. “How can you feel anything but desperate?”

“I definitely feel very, very worried and frustrated,” he said, a bit thrown off balance. “Exactly at the moment when we need a resilient biosphere, we are losing it. If we get too far from planetary boundaries, feedbacks from Earth will start to amplify our trajectory irreversibly toward a four-, five- or six-degree world.” Long pause.

“How can we stay focused in a constructive way on the little glimmer of light that’s there?” he asked, as I hung on his every word. “To begin with, what choice do we have?” Rockstrom’s sombre warnings are reassuring only in so far as they confirm my reasons for feeling glum. And while I do not doubt the truth of Churchill’s dictum – “I am an optimist; it does not seem too much use being anything else” – it’s hardly a morale booster.

Spending two hours with the irrepressibly upbeat Katharine Hayhoe, however, was definitely a high. Like Rockstrom, Hayhoe is a top-level climate scientist who spends a lot of time on the road spreading the gospel of climate action, notably in conservative, middlebrow America. Working closely with social scientists, her overarching aim is to “get everyone who’s worried to be activated… When it comes to climate change today, most people are already worried. But we don’t know what to do.”

Hayhoe doesn’t sugar-coat the problem: “Our civilisation was constructed for a climate that no longer exists. Every aspect of our lives on Earth is at risk from climate change.” But she brims with optimism and hope which, she points out, are not the same thing. When you have no worries, you can still be optimistic that the future will be as good or better. “You only need hope when things aren’t going well. Hope comes from suffering,” she explained.

There are several wellsprings to Hayhoe’s exceptionally large reservoir of hope: science, a charitable view of human nature, and her deep Christian faith. “Because of the science, I know at a visceral level that what we do makes a difference,” she said, noting that – in the space of a decade – emissions reduction commitments have seen projections of Earth’s end-of-century surface temperature drop from 5C to 3C above the pre-industrial benchmark. Not good enough, but a huge difference. “Science shows that every little bit matters, and that is actually a pretty hopeful thing.”

Positive despite everything: Climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe talks with actor Leonardo DiCaprio in Washington, DC, on October 3, 2016 (Mandel Ngan / AFP )

Positive despite everything: Climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe talks with actor Leonardo DiCaprio in Washington, DC, on October 3, 2016 (Mandel Ngan / AFP )

Hayhoe believes that a collective “Oh Shit!” moment, sparked by the kind of extreme weather disasters fast becoming the new normal, will propel climate action into high gear. “If you factor in how humans react to disasters, socially, then we could meet the 2C target,” she said, pointing to women getting the vote and civil rights as major changes made possible by rapid shifts in values.

Hayhoe is surely right that people demanding and embracing deep change is what can save us, but I do not share her confidence that our better angels will prevail when the going gets really rough. But in other ways, her words were a lifeline. While she did not dwell on it, anger has clearly been a powerful driver for her.

Hayhoe and her family moved to Colombia when she was nine. “What made me become a climate scientist in the first place was the injustice of it,” she said, with climate change hitting those least responsible for it the hardest. “If you live in a low-income country, when disaster happens you know what it looks like, and it’s very different than what it looks like here.”

What I also found reassuring was her simple idea that you don’t have to carry the burden alone. “There are a million hands on the boulder, and if I had to take my hand off for a little while, that’s OK – somebody else has it.” A permanently tensed muscle in the back of my neck relaxed a little.

It was the third interview, however, that really knocked me for a loop. It was like a breakthrough session of psychoanalysis, and I didn’t even know I was on the couch.

Kangaroos escape an Australian bushfire in Snowy Valley, Cooma on January 4, 2020 (Saeed Khan / AFP)

Kangaroos escape an Australian bushfire in Snowy Valley, Cooma on January 4, 2020 (Saeed Khan / AFP)Clover Hogan is an expert on climate anxiety, and set up an NGO – Force of Nature – in 2019 to address its consequences, especially in young people. “We’re facing not only a climate crisis, but a mental health crisis,” she told me as we stood amid kids playing in a Paris park. The source of that anxiety, she quickly understood, was as much the feeling that humanity was sleepwalking toward a cliff edge as what might happen when we get there. “We run programs helping young people channel their eco-anxiety into action.”

Growing up in rural Australia, Hogan’s best friend was nature.

Watching documentaries, she realised her cherished world was under severe threat. She was 11. She threw herself into environmental activism and at 16 found herself at the watershed COP21 climate summit in Paris. One event she attended was a hotbed of greenwashing called the Sustainable Innovation Forum, underwritten by BMW, Coca Cola and Shell. “I remember thinking it was like going to a conference on lung cancer sponsored by (tobacco giant) Philip Morris,” she said.

But when she saw her country in flames, something snapped. “I had to surrender to that grief. But in so doing, I found a tremendous amount of love, passion and determination, and the understanding that this is not about me or you, but everyone. This is about the future of the planet.”

Hogan chastises journalists like me for falling short in their coverage of the climate crisis. The news media has (finally) learned how to ring the alarm bells, and to talk about the scope of the danger. “It’s like being hit by a train. But we’re not equipped with the skills, knowledge or tools to think about, ‘What can I actually do?’” she said. “A lot of journalists don’t see that as their responsibility; they see their job as to report on the facts in the most objective way possible. They don’t think about the impact of what they are saying.”

In my quest for climate counsel I also turned to an impish old man who set my brain on fire during an interview in 2009. James Lovelock, who died on his 103rd birthday this summer, invented the machine that revealed that we were inadvertently poking holes in the ozone layer and designed an experiment for NASA to prove Mars is bereft of life.

But he will be best remembered for Gaia, his theory – revolutionary in the 1970s – that Earth is a self-regulating system that tends towards stability, a “living planet” in which everything plays a role. It’s why, for example, oceans and forests – straining to keep Earth in balance -- have for decades absorbed half our carbon pollution even as CO2 emissions increased by more than 50 percent. Today, that’s Earth science 101. But Lovelock was also convinced Gaia had a purpose.

“I think the goal is quite simply to sustain habitability, and that natural selection ensures that. Any species on the planet that adversely affects the climate, adversely affects is own progeny and – according to Darwinism – will tend to be eliminated,” he said. Lovelock decided long ago that humanity missed the boat on climate change and that our species is fated to see its numbers vastly diminished. Two years before he died, his view hadn’t changed much. “If we don’t do something about it, we will be removed from the planet,” he told me.

Angry Earth: A burned forest near Mariposa, California, on July 24, 2022 (David Mcnew / AFP )

Angry Earth: A burned forest near Mariposa, California, on July 24, 2022 (David Mcnew / AFP ) Volunteers try to clear a dam filled with plastic near Krichim, Bulgaria on April 25, 2009 (Dimitar Dilkoff / AFP )

Volunteers try to clear a dam filled with plastic near Krichim, Bulgaria on April 25, 2009 (Dimitar Dilkoff / AFP )

Lovelock had an Olympian perspective – he liked the view from space – on humanity’s hour on the stage. “We are like other species before us that massively changed the environment of the whole planet… The photosynthesisers, when they first produced oxygen (more than 2.5 billion years ago), were devastatingly harmful organisms that killed off whole ranges of other species.”

Then marine algae producing a sulphur-laden organic compound that likely caused the planet to be covered in ice more than 650 million years ago. “And then along come humans with communicating intelligence,” he added. “It has had devastating effects on the planet, and we’re seeing it. But if the planet can adapt, and we can adapt, it could in the end make Gaia an intelligent planet, the first in the galaxy.” Even if billions of our kind perish, in other words, “those that survive may have a better planet to live on.”

So where does all this leave me? At a personal level, I realise that I can no longer chronicle, day after day, the accelerating destruction of nature and gathering climate storm as I have done since 2007. It’s not burn-out; it’s self-preservation. There are now a legion of reporters to take my place. Nor can I rally myself to believe, once again, that UN climate negotiations will deliver anything more than bitter disappointment leavened with just enough progress to keep the process from collapsing.

The UN climate summit in Sharm El-Sheikh – the 27th since 1995, and my 11th – will be my last. As for the battle between hope and despair, I find no solace in Lovelock’s vision of a “good Anthropocene” emerging from the ruins of a climate-ravaged world.

Nor do I have the slightest inkling of what it means to share Hayhoe’s faith that we will prevail against all odds in averting catastrophe.

But pessimism doesn’t necessarily mean retreating to the Alps and pulling up the drawbridge. I am still energised by anger – at the lies, the half-lies, the greed, and especially the additional suffering they will bring in an increasingly unequal and unjust world. “Hope is an active verb,” said Hogan. “We continue to hurtle toward climate collapse. That’s what the science says. But you have to be willing to hold both truths, to hold hope and despair in the same breath. They are not polar ends of a spectrum, they’re very much one and the same.”

More importantly, where does all this leave you? You may not have thought about it much, and you may not want to. But like it or not, the reality of climate change is going to encroach on our lives, body and soul. Brace yourselves.

Edited in Paris by blogs and features editor Fiachra Gibbons