Climate change: The 'Oh Shit! Moment'

Marlowe Hood was one of AFP’s science and environment correspondents for five years, from 2007 to 2012. As the threat of climate change looms ever larger, he contemplates just how bad things might be.

It has taken me more than two years to tag & bag the take-away message from my half-decade covering flu pandemics, furtive sub-atomic particles and dying oceans, and I have Godzilla (along with a movie critic) to thank for the light-bulb moment that brought it all into focus.

Despite that long gestation, I felt the stirrings of a swan-song even before finishing my stint on a beat that was one third science, one third health… and 100% climate change. At least that’s the way it felt once I had experienced what Australian philosopher and climate witness Clive Hamilton – author, notably, of ‘Requiem for a Species’ (that would be us) – calls the ‘Oh Shit!’ moment, when the full weight of the calamity threatening to engulf our planet violently crashes through one’s instinctive reluctance to contemplate End Times.

For me, a skeptic by nature and training, that thunderclap came while talking to top scientists who had been asked, for a 2009 conference at Oxford, to imagine a world warmed by four degrees centigrade (seven degrees Fahrenheit). What emerged was a tableau of misery bleak beyond words: water wars, climate refugees in the hundreds of millions, galloping disease vectors, wholesale famine. (The 4 C scenario is today considered an ‘intermediate’ projection by century’s end.)

But the real piss-your-pants shocker was realizing that it may be too late to put the hounds of hell back on a leash. What if, in other words, climate dystopia is not a cautionary fantasy but a baked-in reality towards which humanity is hurtling with blithe abandon? Indeed, what makes climate scientists lose sleep at night – I saw one burst into tears at the thought – is the measurable possibility that mucking about with the planet’s thermostat has irrevocably set in motion natural forces which, in the relative blink of an eye, will make Earth a far less hospitable place for our tender-footed species.

What am I talking about? We recently learned, for example, that a gargantuan ice cube called the West Antarctic Ice Sheet has passed a ‘tipping point’ beyond which accelerated melting – triggered mainly by warming ocean water – has become the engine of its own demise, cause as well as effect. That means that even if we were to shut down every mechanical source of CO2 on the planet tomorrow, the WAIS will dwindle until it vanishes, lifting sea levels by several meters. Bye-bye Bangladesh, along with every other low-lying mega-delta teaming with human beings and the crops that barely feed them. Hello storm surges that will make Sandy look like a windy high-tide. (There will be some climate justice: Florida will go from well-hung to pencil dick, an entire coastline of reckless development erased.) Whether this happens over one century or three doesn’t really matter – there still won’t be enough time to adapt.

And that’s just one of several auto-pilot cataclysms poised to upend the chemical balancing act scientists now call the Earth System. Another is the vast reserve of carbon – several times the amount of CO2 released so far in the industrial era – buried, mostly as methane, in the egregiously misnamed ‘permafrost’ of Siberia and Canada. Sub-Arctic temperatures rising twice as fast as the global average have already started to unearth this toxic buried treasure, and – beyond a certain point – there will be no way to stop it.

The scary part is that we may have already crossed that threshold and not know it.

(AFP Graphics)

(AFP Graphics)Is there a chance these things won’t happen? Of course. There’s also a chance the Sun will implode before I finish typing this sentence. (Whew. That was close.) It’s all a matter of calculating odds, which is the way scientists talk about the future. But if you actually read the studies and listen to the experts, the prognosis is grim indeed, grim as in ‘grim reaper’.

Right about now you should be asking: ‘If things are that bad, why don’t I know this already?’

Maybe you do. Maybe you’ve heard the news … but weren’t really listening. Survival instinct kicks instantly into high gear when one faces a charging rhino or a meth-head waving a Glock. But, paradoxically, humans have a proven penchant for ignoring deadly threats that do not require immediate attention, e.g. a climate cataclysm. Out of sight, out of mind. (Here’s one point, at least, on which Freud and evolutionary psychologists agree. ) Dwelling on the apocalypse, after all, is itself a meme for madness (see: bearded loner with sign, ‘The End is Nigh’).

But it’s not all your fault. The folks in the know – green NGOs, big-league carbon polluters, climate scientists – are all unwilling, each group for its own reasons, to raise a five-bell, DEFCON 1 alarm.

Brand-name environmentalists are still reeling from the spectacular failure in 2009 of what they billed as the ‘last chance’ climate summit in Copenhagen. They went all-in and lost, and have been afraid ever since of sounding shrill. Call it the Chicken Little syndrome. Carbon profiteers, of course, have every reason to downplay the threat. They have cynically spent a lot of money doing just that, whispering in our ear that the risk is doubtful and distant while the cost of acting now would be ruinous. When humanity finally does acknowledge that the clock has run out, Big Oil & Friends will be the first to propose fanciful technical fixes – a billion tiny mirrors in near space, sowing the oceans with iron – to ensure business-as-usual. Finally, scientists are hamstrung by the codes and culture of their profession. Predictions and policy prescriptions both make them queasy. ‘Not my job’ – I’ve heard it a hundred times. (The media, for its part, has made things worse by manufacturing uncertainty. We do love a horse race. As for politicians, one need only remember that they are not elected by future generations.)

But there’s a third force – and this is where Godzilla comes in – that also impedes us from seeing our future as a mashup of ‘World War Z’, ‘The Day after Tomorrow,’ and ‘Contagion’. In a word: hubris. In the 1954 Japanese original, the city-stomping ‘Gojira’ is a radioactive, mutant offspring of our new-found mastery over elemental particles. Splitting the atom held out the promise of war-ending weapons and unlimited energy, but the cost/benefit ratio of the atomic age turned out to be far less advantageous than advertised. Sixty years later, suggests film critic Andrew O’Hehir, Godzilla is back to remind us once again that trying to conquer nature may have dire, unintended consequences.

The notion that our species can and should bend Earth to its collective will is in fact quite new. It emerged during the Enlightenment and bloomed in tandem with the industrial revolution, bolstered by the certitude that Science, Technology and Education would break the chains of rise-&-decline history and propel mankind upward along a never-ending spiral of Progress. For 19th century thinkers of all stripes – from Marx to Mills, from socialists to social Darwinians – human ingenuity and innate superiority would power the transformation, while nature would provide an inexhaustible bounty of raw materials.

In ancient Greek tragedy, hubris – a cocktail of pride and over-confidence – dooms the willful protagonist to an untimely end. But our modern tragedy is playing out on a larger stage, and the central character is arguably humanity itself.

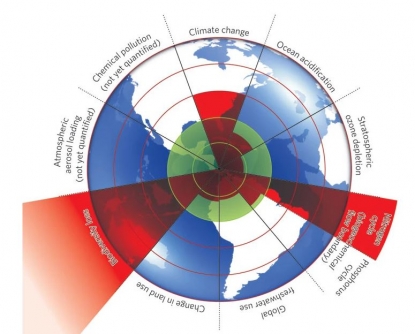

The cult of Progress with a capital ‘P’ continued largely unchallenged until well into the second half of the 20th century. But then red flags started popping up all over the place. Today, the warning signs have morphed into existential threats: a new era of mass extinction, only the sixth in 500 million years; a scourge of diseases no longer cowed by the antibiotics we once thought would wipe them out; giant tears in the fabric of our stratosphere; a crescendo of droughts, fires, floods and storms; oceans rising and dying simultaneously.

For the first time in our planet’s 4.7 billion year history, a single species has not only altered Earth’s morphology, chemistry and biology, but is aware of having done so. The rupture is so radical that many scientists are cohering around the idea that our actions have ushered in a distinct geological era. "We don't know what is going to happen in the Anthropocene,” or the ‘age of humans’, says Erle Ellis of the University of Maryland. “It could be good, even better. But we need to think differently and globally, to take ownership of the planet.”

“Take ownership of the planet.” The hubris of our species has been twofold. First, we imagined that we could bring Earth to heel in the service of our needs and wants. And then, when confronted with abundant evidence that we are poisoning the family well, we persist in believing that we can invent a new source of water.

Even the decades-old battle cry of eco-warriors betrays a misplaced arrogance. When environmentalists demand that we ‘save the planet,’ what they really mean is ‘S.O.S. – Save Our Species’. The planet doesn’t need saving, we do. If humans really do capsize the complex web of chemical and biological interactions that currently sustains life, Earth will find a new equilibrium, as it always has. Our kind, on the other hand, may find the transition very rude indeed.

Think of it this way: God(s) may not be indifferent to your suffering, but Nature is. Only hubris prevents us from realizing that Earth can shake us off like an annoying parasite, allowing some other life form to take our place.

A picture taken on April 19, 2012 in Chaumont-sur-Loire's castle park, in north-central France, shows garden gnomes. (AFP / Alain Jocard)

A picture taken on April 19, 2012 in Chaumont-sur-Loire's castle park, in north-central France, shows garden gnomes. (AFP / Alain Jocard)