An unfinished conversation

The last time I saw Dom was on April 30 after a Gilberto Gil concert. Without planning it, he and I had both bought tickets to see the living legend of Brazilian music play in Salvador, the gorgeous port city on Brazil’s northeastern coast where Dom was living.

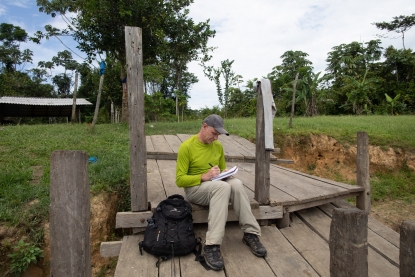

My murdered friend: British foreign correspondent Dom Phillips takes notes in Aldeia Waikay, a hamlet of the Yekuana tribe in Roraima State, Brazil, on November 13, 2019 (Joao LAET / AFP)

My murdered friend: British foreign correspondent Dom Phillips takes notes in Aldeia Waikay, a hamlet of the Yekuana tribe in Roraima State, Brazil, on November 13, 2019 (Joao LAET / AFP)

The next day, the four of us went out together – Dom, his wife, Alê, my wife, Raika, and I. It was pouring rain when we got there. The restaurant was outdoors, and most of the tables were drenched. But then the rain stopped and it turned into one of those magical nights. We were all so happy to be together, we were smiling and laughing the whole time.

I don’t even know how late we stayed – until the bar closed. It was great catching up with him. I hadn’t seen him as much since they left Rio de Janeiro and moved to Salvador to be with Alê’s family.

The riverside community on the Itaguaí River in Atalaia do Norte, Brazil, near the last place where anthropologist Bruno Pereira and journalist Dom Phillips were seen alive, on June 9, 2022. (Joao LAET / AFP)

The riverside community on the Itaguaí River in Atalaia do Norte, Brazil, near the last place where anthropologist Bruno Pereira and journalist Dom Phillips were seen alive, on June 9, 2022. (Joao LAET / AFP)

We spent a lot of time talking about our latest projects. Dom was working on a book about the Amazon, and I was planning a new trip to the region. As usual, we had lots of common ground. He was getting ready to travel to Acre state to visit an Indigenous community, the last descendants of the Incas. And I was on my way to shoot a story about a Kayapo Indigenous community defending their territory against illegal gold miners.

“I wish you were coming,” I told him. “Can’t this time, I’ve got the book,” he said. “But it’s almost finished.” We thought we’d do lots more stories together.

I met Dom in 2019, working together on a story for The Guardian. He was writing about “cattle laundering”, when ranches embargoed by environmental authorities for destroying the rainforest sneak their cows onto the market by passing them through ranches with clean records. It’s a widespread practice.

A herd of cattle in the Amazon rainforest near Sao Felix do Xingu in Para state, Brazil, on September 22, 2021 (Mauro PIMENTEL / AFP)

A herd of cattle in the Amazon rainforest near Sao Felix do Xingu in Para state, Brazil, on September 22, 2021 (Mauro PIMENTEL / AFP)

We travelled to São Félix do Xingu, the heart of Brazilian cattle country, visiting embargoed ranches to document that they were still operating. I took the pictures. It was a complicated story. It’s a lawless, violent region, and cattle men don’t usually like outsiders poking around. Covering environmental crimes is dangerous everywhere in the Amazon, actually. It’s only gotten worse under President Jair Bolsonaro, whose government has gutted environmental protections.

That was the first of several trips Dom and I took to the Amazon. We became friends right away. We had a shared passion for the rainforest. He was living in Rio then, and we would meet up for drinks at great little hole-in-the-wall bars.

Intrepid: Dom Phillips on a reporting trip with Indigenous people in Aldeia Maloca Papiú, Roraima State, Brazil, on November 16, 2019. (Joao LAET / AFP)

Intrepid: Dom Phillips on a reporting trip with Indigenous people in Aldeia Maloca Papiú, Roraima State, Brazil, on November 16, 2019. (Joao LAET / AFP) Dom Phillips (centre) interviews two Indigenous men in Aldeia Maloca Papiú, Roraima State, Brazil in November 2019 (Joao LAET / AFP)

Dom Phillips (centre) interviews two Indigenous men in Aldeia Maloca Papiú, Roraima State, Brazil in November 2019 (Joao LAET / AFP)

He always knew the places with the cheapest beer and best food. He had this wonderful warmth and sense of humour. I remember him consoling me once about a story I couldn’t seem to sell anywhere. “João,” he said, “some stories are like that: we’re the only ones who love them.”

The last assignment I went on with him was another story for The Guardian, about illegal gold mines destroying the Yanomami Indigenous reservation, the biggest in Brazil. It was an amazing trip. We visited two communities that had been invaded by wildcat miners, and went to the mining camp too.

Inacio Vilela, a Brazilian "garimpeiro", or illegal gold miner, and Munduruku Indigenous people, talk to AFP after a garimpeiros protest in Morais Almeida, Itaituba, Para state, Brazil, on September 13, 2019 (Nelson ALMEIDA / AFP)

Inacio Vilela, a Brazilian "garimpeiro", or illegal gold miner, and Munduruku Indigenous people, talk to AFP after a garimpeiros protest in Morais Almeida, Itaituba, Para state, Brazil, on September 13, 2019 (Nelson ALMEIDA / AFP)

Dom wanted to understand the miners’ perspective. He didn’t just see them as villains. He knew they were poor people trying to make a living. He was always looking for ways for people to live off the rainforest without destroying it. Whenever he did a story on something negative, he always tried to find a positive angle to balance it. I find that inspiring.

The trip I was planning when Dom and I met up in Salvador ended up lasting four weeks – way longer than I thought. By the time I got back, he had finished his own trip and left for another, travelling with anthropologist Bruno Pereira in the Javari Valley, near the Peruvian and Colombian borders.

Dom admired Bruno’s work with Indigenous peoples in the region, which has the biggest concentration of uncontacted tribes on Earth. Bruno was helping protect Indigenous lands against illegal logging, mining and poaching.

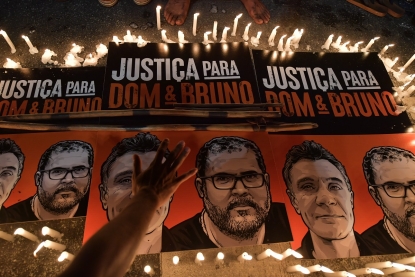

Brazilian Indigenous people protest over the murder of British journalist Dom Phillips and Brazilian Indigenous affairs specialist Bruno Pereira, in Sao Paulo, Brazil, on June 23, 2022 (Nelson ALMEIDA / AFP)

Brazilian Indigenous people protest over the murder of British journalist Dom Phillips and Brazilian Indigenous affairs specialist Bruno Pereira, in Sao Paulo, Brazil, on June 23, 2022 (Nelson ALMEIDA / AFP)

I didn’t even know Dom was in the Javari Valley. I only found out when Alê called me that Monday – June 6. She was panicking. “João, I need your help,” she said. “I don’t know where Dom is. He was supposed to be back by now.”

“Don’t worry,” I told her. “I just got back from a four-week trip that was supposed to last two. It happens in the Amazon.” “But he had a satellite phone,” she said. I started to worry too. If he had a sat phone, he should have been in touch. Something was wrong.

The view from a Brazilian helicopter taking part in the search for Bruno Pereira and Dom Phillips along the Itaquaí River in Atalaia do Norte, Amazonas state, Brazil on June 10, 2022 (Joao LAET / AFP)

The view from a Brazilian helicopter taking part in the search for Bruno Pereira and Dom Phillips along the Itaquaí River in Atalaia do Norte, Amazonas state, Brazil on June 10, 2022 (Joao LAET / AFP)

By the next day, it was a world news story. AFP called asking if I had photos of Dom. He and I had always taken pictures of each other on our trips – not for work, just snapshots we took for fun. I called Alê and asked if it would be OK to publish some. “Definitely,” she said. “The more people who see the story, the better.”

The pictures got published all over the world. I had always thought of them as family photos. Suddenly, it seemed like they were everywhere. The next day, Carl de Souza, the AFP Brazil photo chief, called and said they’d like me to travel to the Javari Valley to cover the search.

Brazilian police and firefighters leave the port of Atalaia do Norte city to search for Bruno Pereira and Dom Phillips on June 11, 2022

(Joao LAET / AFP)

Brazilian police and firefighters leave the port of Atalaia do Norte city to search for Bruno Pereira and Dom Phillips on June 11, 2022

(Joao LAET / AFP) Police head to the place where the bodies of Bruno Pereira and Dom Phillips were buried by their killers on June 15, 2022

(Joao LAET / AFP)

Police head to the place where the bodies of Bruno Pereira and Dom Phillips were buried by their killers on June 15, 2022

(Joao LAET / AFP)

I’m a freelancer. Normally, I’m happy to get an invitation like that from AFP, which is a great agency with worldwide reach. This time, I just felt sad.

But I also felt I needed to be there. So I caught a plane out of Rio and started retracing the same path Dom had followed a week before. I flew to Manaus, then Tabatinga, then caught a boat up the Amazon River and finally a car to Atalaia do Norte, the town he and Bruno set out from on June 2.

I threw myself into work. It wasn’t an easy story to cover. The Javari Valley is thick jungle, and we spent all day, every day dirty and drenched in sweat, working late into the night. One night I camped out in the forest with the Indigenous volunteers leading the search effort. Through it all, I was trying to hold onto hope for Dom – but I cried every day.

A member of the Union of Indigenous Peoples of the Javari Valley searches for Dom Phillips and Bruno Pereira on June 13, 2022 (Joao LAET / AFP)

A member of the Union of Indigenous Peoples of the Javari Valley searches for Dom Phillips and Bruno Pereira on June 13, 2022 (Joao LAET / AFP)

It was tricky to navigate where the next news would break: on the snaking brown rivers where the search was happening, or back in town, where investigators were questioning the first suspects – allegedly poachers seeking payback for Bruno’s work fighting environmental crimes on Indigenous lands. Ironically, like the illegal gold miners, Dom wanted to tell their story, too.

Then there was the internet issue. Like a lot of the Amazon region, the only internet in Atalaia is via satellite. The mayor’s office, which has the best connection, kindly shared their wifi with the world media that had descended on the far-flung little town. But sending photos took hours, and sending videos was worse. There were times I felt like tearing my hair out watching as the “percent uploaded” graphic moving backwards rather than forward. It didn’t help my anxiety. There were times I thought I’d have a breakdown.

The task force head to the spot where a suspect said the bodies of Bruno Pereira and Dom Phillips were buried in Atalaia do Norte, Amazonas state, Brazil, on June 15, 2022 (Joao LAET / AFP)

The task force head to the spot where a suspect said the bodies of Bruno Pereira and Dom Phillips were buried in Atalaia do Norte, Amazonas state, Brazil, on June 15, 2022 (Joao LAET / AFP) Federal police arrive at the port of Atalaia do Norte with what are believed to be the bodies of Bruno Pereira and Dom Phillips, on June 15, 2022 (Joao LAET / AFP)

Federal police arrive at the port of Atalaia do Norte with what are believed to be the bodies of Bruno Pereira and Dom Phillips, on June 15, 2022 (Joao LAET / AFP)

Slowly pieces of the puzzle started emerging from the valley’s web of murky waterways. The authorities – led by the crack Indigenous search team, though officials were reluctant to admit it – first found Dom’s backpack, Bruno’s health card and other belongings; then what looked like a grave; then their bodies.

It was the kind of thing you never want to photograph. But at the same time, I wanted to do my best. I was committed to seeing the story through. I was one of the first journalists to arrive, and one of the last to leave, more than two weeks later.

My pictures got published all over the world. That’s been difficult to process. I’m grateful for the recognition, but I wish it would have been for a different story. I didn’t want it to be like this. It hits me in the stomach.

I keep thinking back to that night in Salvador, Dom and I each about to leave on our respective trips to the Amazon. “Take care, you two,” said our wives. “See you soon,” Dom and I said as we all hugged goodbye.

Dom Phillips takes notes as he talks with Indigenous people at the Aldeia Maloca Papiu, Roraima State, Brazil (Joao LAET / AFP)

Dom Phillips takes notes as he talks with Indigenous people at the Aldeia Maloca Papiu, Roraima State, Brazil (Joao LAET / AFP)

We were supposed to meet up again to share our stories from those trips. I wanted to hear all about his travels to see the descendants of the Incas. He loved history. I’m sure he came back with amazing stories. And I wanted to tell him all about my trip with the Kayapo – about my four weeks living like a hunter-gatherer in the rainforest, about the incredible pictures I got of Indigenous warriors detaining a gang of gold miners. We had so much to talk about.

That unfinished conversation is what’s hardest. But Dom would want this story to have a positive ending. So I’d rather end it by saying this. The Indigenous communities and others defying all odds to save the Amazon in the face of a hostile government give me tremendous hope. I’ll spend the rest of my life telling that story.

He’s given me one more big reason to do so.

João Laet is a photojournalist based in Rio de Janeiro