Love and fear of dying in the time of coronavirus

Paris -- I have long assumed that I would one day succumb to a lung infection. A nearly fatal bout of tuberculosis when I was four left my lungs vulnerable to pathogens, whether bacterial or viral. I’ve had pneumonia twice, and can rarely get rid of even garden-variety bronchitis without recourse to antibiotics. Just a matter of time, I thought, before a nasty bug would burrow into my ageing bronchioles and not let go.

As I watched the coronavirus creep across the globe from ground zero in central China and reported on the risk profiles emerging from the first data sets, I felt the target on my back grow bigger: male, 64 years old, overweight, prone to lung infection.

And when the virus reduced me to a quivering, feverish shambles in less than an hour – morbidly enough the time it took to edit a Q-&-A on COVID-19 mortality rates – I thought to myself, "That’s it, my number’s up."

Today I say: I feel lucky to be alive.

The fear of dying is highly subjective. The thought of getting on a commercial airliner – the safest mode of mass transit – may strike terror into the same person whose pulse barely quickens in a firefight. But that doesn’t make fear any less real. When it wells up like a tsunami and floods your mind, it can feel like you’re drowning.

In hindsight, I know that I never got close enough to knock on death’s door. I suffered excruciating pain and relentless bouts of high fever (40C/104F) for 12 days while in isolation at home, but my body held firm. I spent a week in hospital, but didn’t need intensive care. My lungs were infected with a mix of virus and bacteria, but it didn’t graduate to acute respiratory syndrome.

But hindsight is 20/20. Real time isn’t. The virus toyed with my body, and messed with my mind.

An employee makes a coffin at the Yago Gonzalez coffin-making factory in Pinor, northwestern Spain, on April 14, 2020. (AFP / Miguel Riopa)

An employee makes a coffin at the Yago Gonzalez coffin-making factory in Pinor, northwestern Spain, on April 14, 2020. (AFP / Miguel Riopa)I knew, and doctors warned me, that things could take a sharp turn for the worse one week after the symptoms appeared. I counted the days, repressing a growing sense of dread. But on Day 6, I felt better. My temperature dropped for the first time below 38C/100F, the body pain eased. I allowed myself to see a glimmer of light at the end of the tunnel.

The next day the virus hit me like a sledgehammer, and kept pounding for five days.

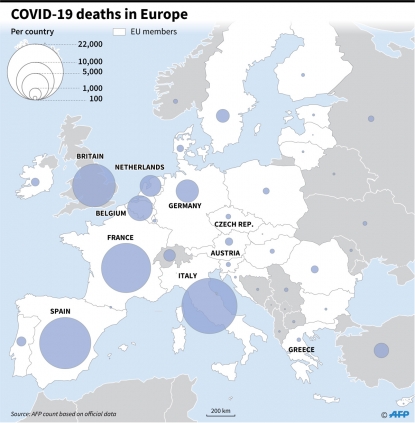

(AFP Graphics)

(AFP Graphics)Most debilitating were the stabbing spasms of pain in my legs. The coronavirus can cause a broad array of symptoms including fever, coughing, scratchy throat, shortness of breath, nausea, diarrhea, loss of smell and muscle pain. But some viruses, I am convinced, seek out weaknesses in the hosts they invade.

In my case, that would be neurological damage that occurred a decade ago when a benign tumor was removed from my spinal column. The surgeon cut out every bit of the growth but mucked up the electrical wiring connected to my lower extremities. I had to learn how to walk again. The most lasting memento from that surgery, however, has been chronic nerve pain in my legs. Stress and fatigue, especially in combination, make it worse, sometimes unbearable.

I mention all this for a reason. The coronavirus did not give me flu-like muscle aches, as it often does, but it did zero in on my damaged nerves. The pain was far more intense and insistent than anything I had experienced before. I became so desperate that I found an old cache of codeine, but that barely helped. A dose of Xanax – designed to treat anxiety and panic, and I was getting pretty panicky – allowed me to sleep for a few hours, but provoked gruesome nightmares. When I took the drug again, it made me sick. It occurred to me that the electric shocks and sleep deprivation I was experiencing was literally a form of torture.

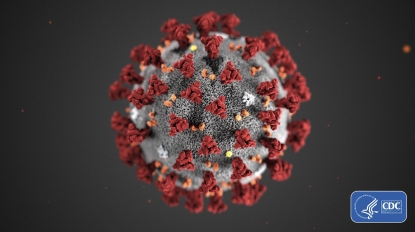

This handout illustration image obtained February 3, 2020, courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and created at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), reveals ultrastructural morphology exhibited by the novel coronavirus, COVID-19. - Note the spikes that adorn the outer surface of the virus, which impart the look of a corona surrounding the virion, when viewed electron microscopically. A novel coronavirus, COVID-19 was identified as the cause of an outbreak of respiratory illness first detected in Wuhan, China in 2019. (AFP /Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/ Alissa Eckert/HO)

This handout illustration image obtained February 3, 2020, courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and created at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), reveals ultrastructural morphology exhibited by the novel coronavirus, COVID-19. - Note the spikes that adorn the outer surface of the virus, which impart the look of a corona surrounding the virion, when viewed electron microscopically. A novel coronavirus, COVID-19 was identified as the cause of an outbreak of respiratory illness first detected in Wuhan, China in 2019. (AFP /Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/ Alissa Eckert/HO)On Day 11, what I feared most came to pass. During the night, when all was silent, I heard a telltale flutter every time I exhaled, like the muffled warning of a diamondback poised to strike. It was a familiar sound I knew from my own bouts with lung infection, and the times I have kept vigil over loved ones in their final days. AKA the death rattle. My fever had crept above 39C/102F, and no amount of paracetamol could bring it down.

In my delirium, I began to think about the end game. I asked myself, as if conducting an interview, whether I was at peace with the idea of dying. To my surprise, there was no panic. “I have so many things to do, but I have lived a rich life,” I responded. But then I thought of my wife and two daughters, and was immediately overcome, pushing back tears. I started to compose letters to each of them in my head, vowing to write them come daylight.

But what could I say to my oldest, who is 22? A lack of oxygen at birth left her unable to add 1+1 or to walk down the street without someone at her elbow, yet she has rare emotional intelligence and an outsized capacity for empathy. Last year I rushed into her room to find her sobbing, something she never does. She looked at me, her eyes brimming, and said: “Michael Jackson is dead.” Somehow, ten years after the king of pop perished, she had grasped the finality of death. What words could I leave her about my own? There were none. I was lost. And how cruel to part with her younger sister, with whom – as she prepared to go to London for her first year of university – I was finally able to share wonder and wonderful things after the tumult of a troubled adolescence? And how could I abandon my life companion of 35 years at the juncture in our story when a deeper kind of happiness seemed at hand?

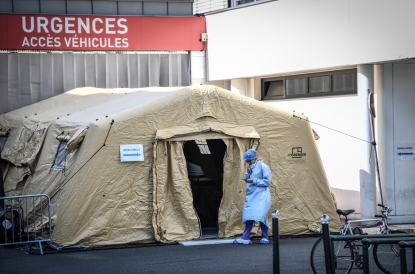

(AFP / Boris Horvat)

(AFP / Boris Horvat)This was my darkest moment. My chest heaved uncontrollably, sparking fits of coughing. Exhausted and depleted by my 12-day ordeal, I was in despair.

The next morning, my breathing became shallow. I dragged myself to my doctor, a wizard with a stethoscope. She confirmed that my lungs were encumbered and prescribed some antibiotics for what she thought were secondary infections. I barely made it back to the apartment. I finally decided that I needed to call ‘15’, the French equivalent of ‘911’ in the US, where I’m from.

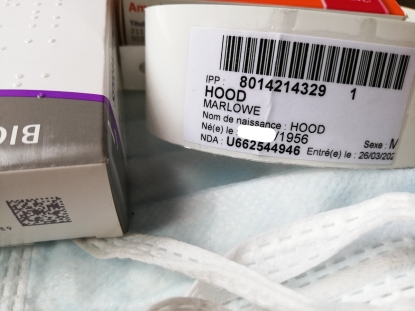

The author's eldest daughter eats in front of the door leading to a room where he was isolated during his bout with COVID-19. (Photo courtesy of Marlowe Hood)

The author's eldest daughter eats in front of the door leading to a room where he was isolated during his bout with COVID-19. (Photo courtesy of Marlowe Hood)I was acutely aware of the fact that France’s emergency rooms and ICUs were filling up. In some regions they were already overflowing, and the death toll was mounting every day. It took me about 20 minutes to get through to someone. After a lot of questions, and pauses to consult a doctor, I was told that a Red Cross team was on its way to my apartment.

Within a half-hour, a woman and two men – all in their 20s – dressed in personal protective equipment from head-to-toe were at my bedside. My wife told me later they were volunteers. One had told her that people were dying of heart attacks before they could even get through to a hotline.

The medics checked my O2 levels, my breathing, took my temperature, listened to my lungs. More calls to doctors. The leader of the team then asked me a surprising question: “Do you want to go to the hospital?” I answered: “That’s not my call.” But he insisted. I said: “I would certainly feel more reassured.”

Finally I was transferred by ambulance to Pitié Salpetrière, a huge teaching hospital close to my home in the 13th arrondissement of Paris. I was ushered out of the apartment in a wheelchair as I waved to my family, wondering if I would ever see them again.

(AFP Graphics)

(AFP Graphics)I arrived a few minutes later at what I recognized as the emergency wing of the hospital, which had been converted into a COVID-19 screening unit. The hospital had added tent structures near the entrance, where I was processed. During those 15 minutes, another six or seven patients arrived by ambulance.

My gurney was wheeled into the main building, where I waited another 45 minutes in an open area crowded with other arrivals, mostly people of color, in wheelchairs or on gurneys. Finally I was transferred into Box #8, a bare bones private space with a sink and a chair. After about 30 minutes, a nurse and a novice ambulance paramedic came in to draw blood and stick a catheter in a vein so I could be hooked up to an IV drip. The paramedic looked at the back of my hand and balked. “Do you want to do this?”, he asked the nurse. “Nah. You need the practice,” she responded. “Do you mind? I don’t have much experience”, he said. “Happy to be your guinea pig,” I responded. Next was the famous PCR test to see if I had the virus. Another nurse stuck a swab-on-a-stick waaay up my nose and twirled it. A couple of hours later I was wheeled off to get a CAT-scan.

A member of the medical staff looks at her phone outside an emergency entrance tent set up at la Pitie-Salpetriere hopital in Paris, on March 27, 2020. (AFP / Stephane De Sakutin)

A member of the medical staff looks at her phone outside an emergency entrance tent set up at la Pitie-Salpetriere hopital in Paris, on March 27, 2020. (AFP / Stephane De Sakutin)It took three hours for all the results to come in. Finally a doctor came and said that I had the virus, and would be transferred to another wing of the hospital. When that happened, I found myself in a private room with its own toilet and shower. It felt opulent. Everyone from the cleaning staff who wiped the floors twice a day to the doctors who came by at least once a day was friendly, attentive and professional. We all, of course, wore masks. I began two courses of antibiotics and had my vitals – especially O2 saturation and breathing cadence – checked every three hours.

Once settled in, I was overwhelmed with relief. I was in the right place. France’s health care system – identified in 2000 by the World Health Organization as the best in the world – has suffered since then due to harsh budget cuts. But it is still world class, and more egalitarian than most. I tweeted.

How lucky I am to live in a country — France — with a world-class, accessible-to-all healthcare system. #COVID2019 pic.twitter.com/CgNhnYtU5G

— marlowehood (@marlowehood) March 27, 2020

Let me say it again: I feel lucky to be alive.

I was deeply moved by how many friends, colleagues and professional contacts responded with words of encouragement.

But then something I didn’t expect happened: dozens, then hundreds, and finally thousands of people in France “liked”, retweeted or responded to my tweet. Many expressed gratitude for my comment, saying that too few French people realized how lucky they were. The same sentiment erupts every evening when Parisians stand at their windows clapping and banging pots to salute their heroic healthcare workers.

Inhabitants applaud at 20:00 along with others across the French nation, to show their support to healthcare employees in Paris, on April 14, 2020. (AFP / Martin Bureau)

Inhabitants applaud at 20:00 along with others across the French nation, to show their support to healthcare employees in Paris, on April 14, 2020. (AFP / Martin Bureau)I sent the tweet because I was genuinely grateful. I also wanted to draw a contrast with the United States, my home country where nearly 30 million people lacked health insurance in 2018 (the most recent official figure) and millions more are saddled with expensive, bare-bones policies that oblige them to pay huge amounts out-of-pocket when they get sick.

Tomorrow, I will be able to touch my wife’s cheek and hug my children for the first time in 30 days. Do I have immunity? Probably. Am I no longer infectious? Very likely. But the truth is, we just don’t know for sure. I will go back to reporting on the pandemic, and the death and suffering trailing in its wake. I will also come back to my main preoccupation, that other existential threat still hanging over our future: the climate crisis. History will recognize a pre- and post-coronavirus world, and right now we are in the twilight zone between the two. The choices we make now – as individuals and nations – will determine whether our species thrives or simply survives.

And yes, I am lucky to be alive.

Marlowe Hood returned home to his family on Monday, April 13. He is healthy and, like nearly all AFP staff at headquarters, working remotely from home. When he’s not in front of a computer and with his family, he is to be found in the kitchen cooking up a storm. Everything, he reports, tastes better post COVID-19.

Editing by Yana Dlugy in Paris.

(Photo courtesy of Marlowe Hood)

(Photo courtesy of Marlowe Hood)