Crime archives

Ludwigsbourg, Germany -- The sign above the metal file cabinet at the entrance of the room says “As of December 31, 2017 -- 1,735,362 files. 1,111 names added over the past four months.”

The room is filled with file cabinets. The folders inside contain the names of Adolf Hitler, Joseph Goebbels, Adolf Eichmann and hundreds of thousands of other criminals of the Nazi regime, down to its “lowliest” executioners -- the guards, accountants, men, women and sometimes children who did various work in the concentration camps.

Jens Rommel and his team add new folders to the collection each month, some 73 years after the fall of the Third Reich. The names are flushed from camp archives and from all over the globe, especially South America, where numerous Nazis took refuge after the war. The team of lawyers have been charged by Germany’s 16 regions to search for Nazis who are still alive in order to bring them to justice before it’s too late. As most of the war survivors are now approaching the 100 year mark, the task has become more and more urgent.

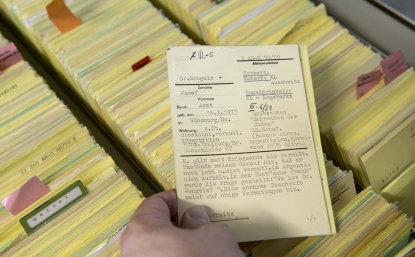

An index card with information on Josef Mengele, the Nazi doctor who performed deadly experiments on prisoners in the Auschwitz concentration camp, at the German office investigating Nazi crimes.

(AFP / Thomas Kienzle)

An index card with information on Josef Mengele, the Nazi doctor who performed deadly experiments on prisoners in the Auschwitz concentration camp, at the German office investigating Nazi crimes.

(AFP / Thomas Kienzle)Rommel’s team works out of the Office for the Elucidation of Nazi Crimes, which is located in the town of Ludwigsbourg, near the city of Stuttgart. A prosecutor by trade, Rommel took the helm three years ago. I and my colleagues are free to work with the archives until 4:00 pm every day and Rommel patiently answers any questions that I have, hiding nothing of Germany’s darkest hours -- a transparence that’s refreshing in today’s world, where tight communication control is everywhere from governments to the private sector.

I’ve lived in Germany for 17 years and up till now have always written about the Holocaust and Nazism from the point of view of the victims and remembrance, never from the point of view of the executioners.

I visited Auschwitz as a student and Buchenwald shortly after coming to Berlin to work as a journalist, and in 2015, I attended a moving ceremony at Dachau, overseen by Chancellor Angela Merkel on the 70th anniversary of the camp’s liberation.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel at the former Nazi concentration camp of Dachau in May, 2015, 70 years after it was liberated by American forces.

(AFP / Christof Stache)

German Chancellor Angela Merkel at the former Nazi concentration camp of Dachau in May, 2015, 70 years after it was liberated by American forces.

(AFP / Christof Stache)When you live in Germany, you never really escape the Holocaust. It lurks everywhere and can jump out at you at any moment as you go about your day. In Berlin, all you have to do is take the S-Bahn until the Oranienburg final stop, then hop on a bus and you’ll be on the site of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

On this particular spring afternoon, Rommel opens the folders that I ask for.

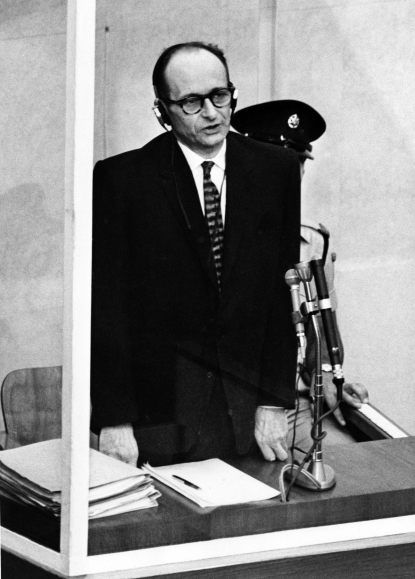

Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann testifies on the first day of his trial in an Israeli court, April 11, 1961, in Jerusalem.

(AFP / -)

Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann testifies on the first day of his trial in an Israeli court, April 11, 1961, in Jerusalem.

(AFP / -)Last name: Eichmann

First and middle names: Adolf Otto

Date of birth: March 19, 1906, Solingen

Director of RSHA (Reich Main Security Office), Service IV B4, Jewish and deportation affairs.

Then come in minute detail all the functions that one of the Holocaust’s main organizers was in charge of. It finishes with his trial, death sentence and execution by hanging in Israel in 1962, following his capture by Mossad agents in Argentina in May 1960.

The file doesn’t say anything about people ripped from their lives and sent into hell by the Nazis, the pounding on apartment doors, the terrified people assembled on the streets, in the train cars, inside the gas chambers. But knowing what has happened, you can’t help but be horrified by the scale of the crime.

The archive room is filled with metal filing cabinets and each one contains thousands of folders.

Germany could have digitized these documents -- at most they would have taken up a few computer hard drives. But Germany made another choice.

While my photo and video colleagues adjust light ahead of our interview with Rommel, I stroll around the room and take a peek into a neighboring one, which holds witness testimony, records of trials and indictments that were handed down when Germans finally began to examine their past and to ask uncomfortable questions of their parents and grandparents. I take a look inside some of the drawers. They contain names completely unknown to me, all cogs in the Nazi machine.

The names of people and places are everywhere you look in the room. There are more than a million folders here. I suddenly feel ill and think of the phrase coined by author Hannah Arendt, a German Jew who evaded the Holocaust by fleeing the country in 1933 and who covered Eichmann’s trial for the New Yorker -- “the banality of evil.”

Most of the people in these folders were but one cog in the Nazi bureaucratic chain of command. Eichmann was a mediocre and zealous bureaucrat. How many of these folders contain names of other mediocre and zealous bureaucrats, who didn’t think about their moral implication in a genocide?

Convicted former SS officer Oskar Groening, 94, listens to the verdict at his trial on July 15, 2015 at court in Lueneburg, northern Germany. He was found guilty of being an accessory to murder at the Auschwitz concentration camp. (AFP / Tobias Schwarz)

Convicted former SS officer Oskar Groening, 94, listens to the verdict at his trial on July 15, 2015 at court in Lueneburg, northern Germany. He was found guilty of being an accessory to murder at the Auschwitz concentration camp. (AFP / Tobias Schwarz)Rommel’s office lies in a peaceful, laid-back corner of Germany. Unemployment is low, blooming flowers are everywhere, and locals are known for being frugal.

Streets are lined with neat houses where the front yards are clean and neat, where kids ride their bikes home from school and women stroll with baby carriages along quiet streets.

The place perfectly embodies a Germany that came out of World War II -- shamed and annihilated, it rolled up its sleeves to rebuild itself into a rich, economic, democratic nation. A reliable country with an exemplary democracy… until recently, when old demons began to rear their heads.

The writing Arbeit Macht Frei (Work Sets You Free) can be seen at the gate of Sachsenhausen concentration camp memorial on September 03, 2010 in Oranienburg, northeastern Germany. (AFP / Johannes Eisele)

The writing Arbeit Macht Frei (Work Sets You Free) can be seen at the gate of Sachsenhausen concentration camp memorial on September 03, 2010 in Oranienburg, northeastern Germany. (AFP / Johannes Eisele)During the last legislative election, more than 90 deputies of the far-right anti-refugee, anti-Islam AfD party were elected to parliament. Something has changed in Germany.

Like on January 27, the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz and Holocaust Remembrance Day, when it is traditional for Bundestag deputies to invite a Holocaust survivor to address the chamber.

This year, it was a woman named Anita Lasker-Wallfisch. During a powerful speech, she reminded deputies that “hate is poison” that always ends up infecting those who embrace it. She spoke of the world’s closing its doors to Jews fleeing Germany after Hitler’s rise to power in 1933 and she thanked Germany for its generous act in 2015, when it took in a million refugees, many of them Syrians fleeing war in their country.

After her speech, the chamber erupted in a standing ovation. Imagine more than 700 deputies, as well as the chancellor and her government, on their feet, applauding this elderly woman who decades ago was deported to Auschwitz, where she survived only because of her love of the violin -- she joined the camp orchestra while her parents perished in the gas chambers.

But one of the deputies, Hansjoerg Mueller of the AfD, remained seated. The only one. Eventually he got to his feet, but pointedly refused to applaud the Holocaust survivor. In Germany! This would have been unthinkable a few years ago.

After the latest outrageous statement by an AfD deputy, a German colleague told me “some of these statements would have never been possible just a few years ago.” But in today’s Germany, some things are once again possible.

German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier and Holocaust survivor and cellist Anita Lasker-Wallfisch arrive for the annual ceremony in memory of Holocaust victims and survivors, on January 31, 2018, at the Bundestag (Germany's lower house of parliament).

(AFP / John Macdougall)

German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier and Holocaust survivor and cellist Anita Lasker-Wallfisch arrive for the annual ceremony in memory of Holocaust victims and survivors, on January 31, 2018, at the Bundestag (Germany's lower house of parliament).

(AFP / John Macdougall) Holocaust survivor and cellist Anita Lasker-Wallfisch receives a standing ovations after addressing the Bundestag (Germany's lower house of parliament) during the annual ceremony in memory of Holocaust victims and survivors, on January 31, 2018 in Berlin. (AFP / John Macdougall)

Holocaust survivor and cellist Anita Lasker-Wallfisch receives a standing ovations after addressing the Bundestag (Germany's lower house of parliament) during the annual ceremony in memory of Holocaust victims and survivors, on January 31, 2018 in Berlin. (AFP / John Macdougall)

Rommel and I are from the same generation -- neither we nor our parents lived through the horrors of the Holocaust. He tells me that he has “no biographical tie” with either the victims or the executioners. He said he took the helm of the office to humbly examine, before it’s too late, “what the law can still do” to judge the criminals.

That’s one of the reasons why I wanted to do a story on the office -- to take a look at the role of the judge. Rommel tells me that “Germany has a political and moral duty to shine a light” on Nazi crimes “for the victims.”

Friedrich Engel, a 93-year-old former Nazi SS officer, sits 12 June 2002 in a Hamburg courtroom before his trial for allegedly ordering the murder of 59 Italian prisoners more than 50 years ago.

(AFP / Pool/ Christian Charisius)

Friedrich Engel, a 93-year-old former Nazi SS officer, sits 12 June 2002 in a Hamburg courtroom before his trial for allegedly ordering the murder of 59 Italian prisoners more than 50 years ago.

(AFP / Pool/ Christian Charisius) Photo taken in 1946 during the Nuremberg Nazi trials. From left to right, in the front row: Hermann Goering, Rudolf Hess, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Wilhelm Keitel, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, second row: Karl Dönitz, Erich Raeder, Baldur Von Schirach, Fritz Sauckel. (AFP / Stringer)

Photo taken in 1946 during the Nuremberg Nazi trials. From left to right, in the front row: Hermann Goering, Rudolf Hess, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Wilhelm Keitel, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, second row: Karl Dönitz, Erich Raeder, Baldur Von Schirach, Fritz Sauckel. (AFP / Stringer)

As I have followed the last of the Nazi trials over the past several years, I have often asked myself if it made sense to bring charges against these old men, who occupied medium or minor roles during the war, 70 years after the fact, with many of them in wheelchairs.

It can get surreal when some of these nonagenarians, ex-Auschwitz guards, appear before tribunals being charged as minors because they weren’t 21 years old when they allegedly committed their crimes.

To tell you the truth, I’ve often had my doubts about this justice decades after the fact. But I think all those folders stacked in those metal filing cabinets remind us of something very important -- we are responsible for our actions. And these old men never thought they had done something wrong. They never felt guilty of anything.

Jens Rommel at his office, April 19, 2018.

(AFP / Thomas Kienzle)

Jens Rommel at his office, April 19, 2018.

(AFP / Thomas Kienzle)These questions become all the more poignant and relevant given the context of today’s Germany, which has accepted 700,000 Syrian refugees alone fleeing their country’s savage civil war since 2011.

Last November, I did an interview with one of them, 30-year-old Yazan Awad. He is part of a group of Syrians who have brought a suit in Germany against the Syrian regime of President Bashar al-Assad for crimes allegedly committed against them in Syria, at the beginning of what started out as peaceful protests and eventually degenerated into a savage civil war.

Awad says that he was tortured in the al-Mezzeh prison, near Damascus, for having joined anti-regime protests in 2011, when they first erupted. He says he was beaten with cables and with nail-studded bats. Hung by his wrists. Had his jaw broken. Had a barrel of a gun inserted into his anus for hours. His words during our interview still haunt me. “I still hear the cries” of the other prisoners “and the sounds of them being beaten.”

At one point as we talked, he fell silent. He was trembling and gasping for air. The memories became too much. He stood up, then sat back down. His eyes were filled with sadness. And I was there with my tape recorder still running, my black ink pen with its chewed cap, and my life in a free and peaceful country. What comfort could I possible offer this man who has lived through such horrors?

Yazan Awad in Berlin, November, 2017.

(AFP / John Macdougall)

Yazan Awad in Berlin, November, 2017.

(AFP / John Macdougall)All Syrian refugees whom I interviewed, be they opposition activists or just young people who fled war, they all live with the sentiment that Assad and his cronies will never be punished for what they have done.

There has been no justice for the suffering they went through. No senior Syrian officials has been brought to account. Assad is still in power and his smiling portraits hang in the devastated cities of Aleppo and Homs.

Another refugee, Mahmud A., told me how his high school buddies disappeared at the start of the protests, in 2011. One day the teenagers were there, participating in demonstrations, the next they were gone. And silence. When their fathers went to the local authorities to find out about their sons, they were chased away; their mothers pleaded with their other children not to demonstrate any more.

And then, after weeks, some of them re-appeared, shadows of their former healthy teenage selves, covered with bruises and broken limbs, with vacant expressions in their eyes. “You know, Yannick, it was like they had died on the inside,” Mahmud tells me in his broken German.

How do these people build a new life in Germany, when there is no justice for what they have gone through?

A Syrian man shows marks of torture on his back, after he was released from regime forces, in the Bustan Pasha neighborhood of Syria's northern city of Aleppo on August 23, 2012. (AFP / James Lawler Duggan)

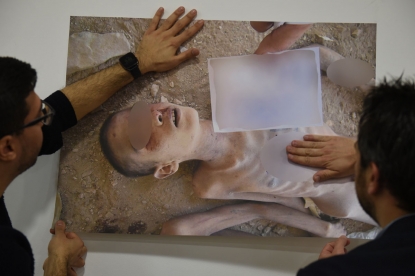

A Syrian man shows marks of torture on his back, after he was released from regime forces, in the Bustan Pasha neighborhood of Syria's northern city of Aleppo on August 23, 2012. (AFP / James Lawler Duggan) Members of the Syrian Organisation for the Victims of War (SOVW) display pictures documenting the torture of detainees inside the Assad regime's prisons and detention centers, on March 17, 2016 in Geneva. (AFP / Philippe Desmazes)

Members of the Syrian Organisation for the Victims of War (SOVW) display pictures documenting the torture of detainees inside the Assad regime's prisons and detention centers, on March 17, 2016 in Geneva. (AFP / Philippe Desmazes)

I think of Awad as I return from Ludwigsbourg. I hope that one day, maybe in 10 years or more, he’ll have a folder with the name and details of one of his torturers, and that having such a folder exist gives him some peace. That one day justice will come knocking on the door of the man who tormented him with the barrel of that gun.

Jens Rommel has a firm conviction that he repeated over and over again during our time together -- it’s important to judge these people. Even if it’s so late, even if the process is far from being perfect. Thinking of the Syrian refugees whom I have met, I have to agree with him.

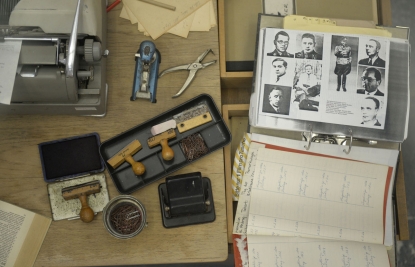

A replica of a typical desk from the early years of the Central Office of the Judicial Authorities of the Federal States for The Investigation of National Socialist Crimes is seen through a glass floor in a permanent exhibition in Ludwigsburg, southwestern Germany, on September 3, 2013. (AFP / Thomas Kienzle)

A replica of a typical desk from the early years of the Central Office of the Judicial Authorities of the Federal States for The Investigation of National Socialist Crimes is seen through a glass floor in a permanent exhibition in Ludwigsburg, southwestern Germany, on September 3, 2013. (AFP / Thomas Kienzle)