At the trial of the "Butcher of Lyon"

Thirty years ago, the “Butcher of Lyon” Klaus Barbie went on trial in France in a landmark case that resulted in painful national retrospection. AFP journalists who covered the trial look back on those days in Lyon, when Barbie -- a former Gestapo officer in the city during World War II who after the war settled in Bolivia before being extradited to France in 1983 -- finally faced charges for the 14,000 deaths he is estimated to have directly caused.

Barbie was put on trial in Lyon, where he operated with such ruthless efficiency during the war as head of the local Gestapo. The city was also known as the “capital of the French Resistance.” His trial began on May 11 and would last nearly two months. It marked the first time that Holocaust victims could talk in a French court about the horrors they witnessed 42 years prior. It also marked the first time a person faced charges of crimes against humanity in France. On July 4, 1987, Barbie was sentenced to life in prison, where he would die of cancer five years later.

Lyon, May 28 (AFP story): “He doesn’t make a dramatic first impression. Short, nearly bald, thin from illness, he looks like a grandfather who is too old to be judged. But his constant ironic smile and his piercing eyes that he never lowers quickly dispel this false impression of fragility.”

Barbie on the first day of his trial, May 11, 1987.

(AFP / -)

Barbie on the first day of his trial, May 11, 1987.

(AFP / -)Philippe Valat: I and the other AFP correspondents had a chance to meet with several witnesses during the long phase of pre-trial proceedings. All of them, without exception, spoke of Barbie having a “sinister” or “sadistic” stare that still haunted some of them in their nightmares. Some of them said that they could immediately recognize, more than forty years later, their former tormentor because of this look in his eyes and because of this smile, which never left his face as he watched them be tortured. When Barbie first appeared in the defendant’s box, he had the same piercing gaze and the same mocking smile that they had described to me. That really made an impression on me.

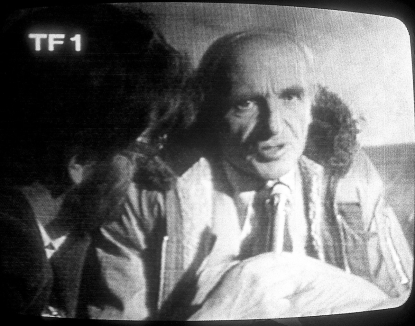

The ever-present smile. Klaus Barbie as a free man, during an interview on January 25, 1972 in Lima, Peru.

(AFP / --)

The ever-present smile. Klaus Barbie as a free man, during an interview on January 25, 1972 in Lima, Peru.

(AFP / --)Christophe de Roquefeuil: Barbie came in. Smiled. Sat down. As if he was a spectator at someone else’s trial. I remember the silence that washed over the huge hall where the trial was taking place, muting the hundreds of people gathered for the affair -- journalists, witnesses, lawyers, spectators. We had all been waiting for this moment for weeks with one question in mind: “What would happen when the 'butcher of Lyon' first appeared? Cries of anger? A disturbance? Would one of the witnesses, some of whom were quite elderly, faint?”

In the end, there was nothing but silence, interrupted by the clicking of photographers’ cameras. And the calm, professional voice of Judge Andre Cerdini who opened the proceedings.

Frederic Bichon: It’s funny, but I can still remember today one of the headlines of that day: “Mister Barbie has nothing to say.” But it didn’t really matter in the end. I would go through a similar experience years later, at the International Tribunal for the ex-Yugoslavia and the International Criminal Court -- in the end, noone is really interested in explanations of people accused of incomprehensible, inhuman acts.

At the start of his trial, this old man could have been anyone’s grandfather, if we ignored for a moment the accusations of the prosecution. Even that famous photo on the opening day, where he appears to be grinning, to me always seem over-analyzed. But the contempt that he would later show toward the witnesses -- to me that was really revealing.

Klaus Barbie at the start of his trial, May 11, 1987.

(AFP )

Klaus Barbie at the start of his trial, May 11, 1987.

(AFP ) Former Resistance member Lise Lesevre, who was tortured by Barbie before being deported to a concentration camp, arrives at the trial on May 12, 1987.

(AFP )

Former Resistance member Lise Lesevre, who was tortured by Barbie before being deported to a concentration camp, arrives at the trial on May 12, 1987.

(AFP )

Frederic Bichon - It was the witnesses who gave the most gravity to the trial, who made the most lasting impressions. Having grown up in the region and attended high school in Lyon, I knew the stories of Izieu, where Barbie oversaw a raid on an orphanage that sent 44 Jewish children and their seven supervisors to concentration camps, and Jean Moulin, the emblematic Resistance hero tortured (some say to death) by Barbie.

But it was the testimony of the witnesses, all the more incredible because nearly all of them were delivered without a trace of hate or anger in their voices, that made impressions that last to this day.

Ahead of the trial, I interviewed Simone Lagrange, who was tortured by Barbie at the age of 13. “I have six million dead behind me,” she said simply.

Philippe Valat: I don’t know why, but the women made the most impression on me. Maybe because some of them lost their children in the most horrid circumstances. And not only did they somehow find the strength to survive such a thing, but they were capable of talking about it without breaking down.

One of the strongest testimonies came from Fortunee Benguigui, who was more than 80 years old at the time of the trial. Her three sons were deported to Auschwitz after the raid led by Barbie in the village of Izieu. She was herself at the concentration camp, thinking her sons were safe.

She realized what had happened to her boys one day at the Auschwitz infirmary. On that day, she saw the son of one of the German doctors wearing a sweater that she had knitted for one of her boys. As part of her testimony, she read a letter that one of her sons had written to her just before being deported.

Throughout her testimony, she refused to sit down. She remained standing without a wince. That was a common thread among many of the witnesses -- despite the advanced age or fragility of some of them, they refused to sit down, they preferred to speak standing.

Two mothers of the Jewish children deported from the Izieu orphanage under Barbie's orders, Itta Halaunbrenner (second from left) and Fortunee Benguigui (second from right) arrive at the trial on June 2, 1987.

(AFP)

Two mothers of the Jewish children deported from the Izieu orphanage under Barbie's orders, Itta Halaunbrenner (second from left) and Fortunee Benguigui (second from right) arrive at the trial on June 2, 1987.

(AFP)When Barbie refused to attend the hearings, some of the witnesses were at first indignant. But in the end, I think that his absence allowed them to recount what had happened to them at ease. And that was one of the major goals of this trial -- to give them an opportunity to present their stories.

Most of the witnesses were advanced in age, but some of them were relatively young, like Simone Lagrange, who was less than 60 at the time of the trial. I think that for people of my generation (I was 29 old at the time), it made us realize just how recent this history had been. I suppose that nearly all of the witnesses are today deceased, which proves the pertinence of the argument at the time, that it was imperative to hold this trial before it was too late.

Philippe Valat: Another point that struck me was the absolute silence that reigned during witness testimony. Some of the witnesses were speaking in public for the first time.

Much of the testimony was difficult to hear. There was that of Mrs. Benguigui. There was also that of a former Resistance fighter who described being tortured by electricity in a room in which Barbie made his German shepherd sexually assault a teenage Jewish girl. After that testimony, silence hung for a long time over the proceedings, including the defense lawyers. Anyone hearing testimony like that could not but be affected by it, for a long time afterward.

Barbie in Bolivia in February, 1983.

(AFP / Pascal Pavani)

Barbie in Bolivia in February, 1983.

(AFP / Pascal Pavani) And at his trial on May 11, 1987.

(AFP / Stf)

And at his trial on May 11, 1987.

(AFP / Stf)

Christophe de Roquefeuil: There was a lot of discussion, especially before the trial started, of whether it was necessary or not. Whether it was really necessary to stir up old ghosts; threaten Franco-German reconciliation; open old wounds and shine a light on French compromises during the war. After those testimonies in Lyon, I was more than convinced. The Barbie trial had to be held -- if for nothing else than to give Mrs. Benguigui but a whisper of justice by allowing her to speak of her children in her own words.

Frederic Bichon: I remember several main players in the trial. There was the prosecutor, Pierre Truche, the incarnation of justice without vengeance. There was Nazi hunter Serge Klarsfeld, who along with his wife Beate, played the main role in bringing Barbie to justice by bringing international pressure to force his extradition. I so much wanted to find him a formidable figure, but in the end he proved to be a very poor orator.

Nazi hunter Serge Klarsfeld at his office in Paris ahead of the trial, May 4, 1987.

(AFP / Philippe Bouchon)

Nazi hunter Serge Klarsfeld at his office in Paris ahead of the trial, May 4, 1987.

(AFP / Philippe Bouchon)And then there was Jacques Verges, the defence attorney extraordinaire. His strategy of putting the state on trial was certainly interesting, but at times achieved the perverse result of transforming victims into guilty parties.

Philippe Valat: Barbie’s main lawyer really made an impression on me. We met him before the trial and he was both extremely polite and icy at the same time. He was an intellectual machine, who made an indelible impression but whom you couldn’t read.

Christophe de Roquefeuil: I got the impression that Mr. Verges was putting on the show of his life. His strategy of turning Barbie’s trial into a trial of colonial and collaborationist France to me seemed to show how little interest he had in the personal case of his client. In the end, I don’t think his strategy achieved much -- neither for Barbie, nor for the facts, nor for history.

The four defense attorneys. From left to right: Nabil Bouaita, Jacques Verges, Raul Jimenez, Jean-Martin M'Bemba. June 29, 1987.

(AFP / -)

The four defense attorneys. From left to right: Nabil Bouaita, Jacques Verges, Raul Jimenez, Jean-Martin M'Bemba. June 29, 1987.

(AFP / -)Frederic Bichon: Frederic Pottecher was a famous French criminal justice journalist who at the age of 82 came out of retirement to chronicle the trial. We always found him in offices on the banks of the Saone river, where he made his recordings and regaled us with his stories.

Philippe Valat: He was theatrical, generous and passionate. During his lunches, he gladly entertained the youngest members of the profession at his table.

He had a depth to him that we could only dream of, because he lived through the war and because he covered nearly all the trials following the war. Barbie’s trial was as important to him as that of Adolf Eichmann, which he also covered.

To rub shoulders with this extraordinary journalist made me realize the importance of what I, just starting out in my career, was covering.

Frederic Pottecher, a celebrated French reporter who came out of retirement to cover the Barbie trial, in front of the courthouse on May 19, 1987.

(AFP / Gerard Malie)

Frederic Pottecher, a celebrated French reporter who came out of retirement to cover the Barbie trial, in front of the courthouse on May 19, 1987.

(AFP / Gerard Malie)Philippe Valat: Following the Barbie trial, I began to write with more restraint, limiting, for example, my use of superlatives. Exceptional stories speak for themselves.

Christophe de Roquefeuil: For me, the trial served as a reminder of one of the foundations of journalism -- the importance of eyewitnesses. When events are strong, they speak for themselves and writing should be minimal. You need to reconstruct the emotions of others, without betraying yours.

AFP deployed massive numbers of journalists to cover the Klaus Barbie trial. These included 13 text journalists, six photographers and two illustrators. In addition there were four editorial assistants and two technicians on the ground in Lyon. Bureaus abroad also contributed. The resulting efforts, including text, photos and drawings, were then assembled into a book published by the agency in French, entitled “The Barbie Trial.”

This blog was translated from the French by Yana Dlugy in Paris.