The most German of stories

DACHAU, Germany, May 6 2015 – She lays a hand on his forearm to offer support. She helps him rise from his wheelchair, and take a few faltering steps towards the pulpit where he is to deliver a short speech. They are surrounded by beefy bodyguards, sharp-suited protocol officials and hundreds of guests. But she is the one who leans, in her navy blue raincoat, to help the elderly man whose great age – 95 – is eating away at his strength. Angela Merkel.

Leader of Europe’s most powerful economy, a superstar in her native Germany, where after a decade in power she is nicknamed simply “Mutti”, or Mum, Angela Merkel’s every word is studied, commented, analysed - and reported by AFP.

“Chancellor of the world” headlined the newspaper Bild after one of her diplomatic marathons. At AFP’s Berlin bureau we must watch for the slightest shift in tone on Greece, the euro, Ukraine, Russia, exports, espionage, nuclear power, asylum seekers – sometimes to the point of saturation. The elderly gentleman beside her is Max Mannheimer, a Jewish survivor of the Nazi concentration camps.

French WWII deportee Clement Quentin (L), German Chancellor Angela Merkel (3rd L) and Holocaust survivor Max Mannheimer (3rd R) at a ceremony to mark 70 years since the Dachau death camp's liberation, on May 3, 2015 (AFP Photo / Pool / Andreas Gebert)

French WWII deportee Clement Quentin (L), German Chancellor Angela Merkel (3rd L) and Holocaust survivor Max Mannheimer (3rd R) at a ceremony to mark 70 years since the Dachau death camp's liberation, on May 3, 2015 (AFP Photo / Pool / Andreas Gebert)Merkel’s simple gesture speaks of the humility and repentance of a nation that sent six million Jews to die between 1933 and 1945, along with countless resistance fighters, political dissidents, homosexuals and Roms.

Raining cats and dogs

It is Sunday morning. I am in Dachau for the ceremonies marking the 70th anniversary of the camp’s liberation in 1945. It is raining cats and dogs. We are all drenched, the tents set up for the occasion are too small to accommodate everyone and most of the press has had to stay outside. The Internet connection is barely there, the Chinese television crew next to me is too jumpy for my liking, and the mobile phone network has momentarily packed in.

Visitors at the memorial site of the Nazi concentration camp Dachau on May 3, 2015 (AFP Photo / Christof Stache)

Visitors at the memorial site of the Nazi concentration camp Dachau on May 3, 2015 (AFP Photo / Christof Stache)Notebook in hand I jot down the survivors’ words as they take turns giving a series of short speeches. Which quote is going to open my story? What will we take away from this ceremony? I wonder how on earth I am going to write under the beating rain. Laptops are better suited to dry climes.

In the distance, a crematorium

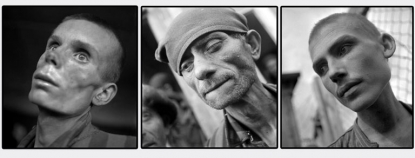

I stop my thoughts in their tracks for a moment, and look up. The chancellor, who was born after the war and lived much of her life in communist East Germany behind a wall that called itself a rampart against fascism, is addressing a group of camp survivors. Old men who chose to return here, 70 years later, to tell the young generation such horrors must never be repeated.

Survivors huddling close together, looking frail and worn in their Sunday suits and ties, clutching medals with dignity to their chests. I know they are most certainly here for the last time. I look around, at the reconstituted barracks once packed with prisoners submitted to forced labour. And in the distance, a crematorium.

Holocaust survivor Max Mannheimer delivers a speech at a ceremony to mark 70 years since the Dachau death camp's liberation, on May 3, 2015 (AFP Photo / Pool / Andreas Gebert)

Holocaust survivor Max Mannheimer delivers a speech at a ceremony to mark 70 years since the Dachau death camp's liberation, on May 3, 2015 (AFP Photo / Pool / Andreas Gebert)All of German identity is here, in this moment. A chancellor, survivors and a death camp. My pen has long since stopped racing across the page. I contemplate the moment, suspended in time.

'Not yet animals, but only just'

A former French resistance fighter, Clement Quentin has just laid a wreath along with Angela Merkel before the monument to the unknown deportee, beside the crematorium oven. A few days ago, the 94-year-old told me in a long interview of the day the Americans liberated the camp, on April 29, 1945.

After 10 months at Dachau, he was “waiting to die” when the US trucks rolled into the camp.

"We were no longer normal human beings, we weren't yet animals, but only just", he told me. Seventy years later he is there in his buttermilk raincoat, straight-backed beside Angela Merkel.

Dead prisoners in a train carriage at Dachau concentration camp, photographed as American trucks liberated the camp in April 1945 (AFP Photo / Eric Schwab)

Dead prisoners in a train carriage at Dachau concentration camp, photographed as American trucks liberated the camp in April 1945 (AFP Photo / Eric Schwab)It is still pouring, but it is not rain that pearls onto my notebook as the vice-president of the International Dachau Committee cries “To the dead!” before a long, long moment of silence, broken only by a clarion call.

The past is ever present

My mind turns to one of the first books I read after arriving in Germany as an AFP reporter in 2001, by a well-known television journalist called Ulrich Wickert. He told of the event that made him realise he was German. He is seated outside the Cafe de Flore in Paris one Spring afternoon. At the table beside him, a woman is sat chatting. The weather is hot. The journalist, a longtime correspondent in France, watches her peel off her jacket.

“She had on a short-sleeved blouse and you could seem perfectly, tattooed on her forearm, a concentration camp inmate number.”

“We were talking. We fell silent. Would she not be hurt to hear the sound of the German language? I was ashamed.”

A US soldier stands outside a gas chamber at Dachau upon the camp's liberation by Allied troops in April 1945

(AFP Photo / Eric Schwab)

A few days later, I came across a billboard at the entrance to a metro station on the Kudamm, the big shopping street in West Berlin which is notably home to the giant Kadewe store, joy of Russian tourists. On the sign, a few words: “The places of horror: Auschwitz, Treblinka, Mauthausen…” The list of the Nazi death camps. Just posted there in the street, in the middle of the consumer bustle. I was beginning to come face to face with the past, which is a such a constant presence in modern-day Berlin.

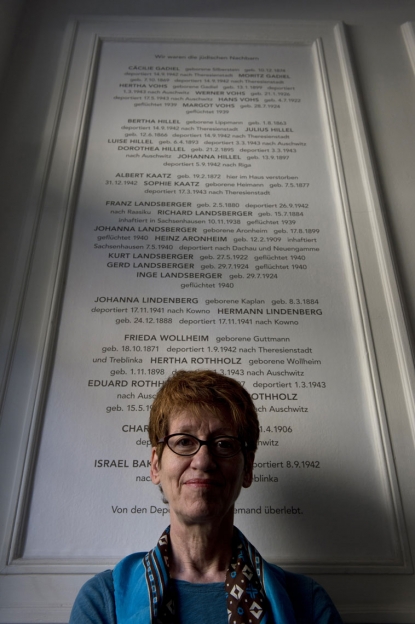

A decade later, I interviewed the residents of an old building in Berlin, which housed many Jewish people before the war. In 2009 they set out to trace the former tenants’ stories. They sifted through dozens of registers, archives and directories to track down the people who lived there before 1933, and who died in Treblinka or Sobibor. Because they were Jewish.

Then they searched out their descendants, as far as Australia. At residents’ meetings they wasted no time discussing what colour to paint the walls, or the size of flowerpots for the garden. They spoke of the family from the third floor, who died in the gas chambers at Auschwitz.

Prisoners at the Dachau concentration camp in April 1945 (AFP Photo / Eric Schwab)

Prisoners at the Dachau concentration camp in April 1945 (AFP Photo / Eric Schwab)Once they had found all the names, they had a plaque laid in their honour at the entrance to the building. They met with me one day in June to share their story.

“I was born after the war,” one of them said to me. “I can do nothing about the crimes committed by the Nazis. But I want to make sure that such a crime never happens again.”

Another told me how he stumbled across a photo, at an exhibition on Jews before World War II, of a brother and sister posing in their Sunday best on a balcony, a few months before they were deported. It was his balcony, he realized, where he likes to relax on a sun-lounger on summer days. If I had to keep just one of all the stories I reported on during my time in Germany, it would be this one. The strongest, the truest, the most German of all.

Yannick Pasquet is an AFP reporter in Berlin

Berlin tenant Gabrielle Pfaff stands in front of a plaque commemorating Jews evicted during the Nazi era

from the building in which she lives (AFP Photo / John MacDougall)