Culture shocks in the open sea

AT SEA ABOARD THE USS GEORGE H. W. BUSH -- "Here we go, here we go, here we go!!!" -- is how the crew of the C-2A Greyhound transport plane prepares us for the landing to come. A few seconds later, I’m brutally squished in my seat, my first landing aboard an aircraft carrier that starts my reporting mission on the USS George H.W. Bush. I’m here because the carrier is playing temporary host to French pilots. I thought it would be a good opportunity to write about what, if any, culture clashes result. I wasn’t disappointed.

The first sight that awaits us as we disembark is an American F-18 next to a French Rafale, engines purring, ready for takeoff. All around us is the blue of the Atlantic Ocean. We’re off the coast of the US state of Virginia. The French planes and pilots are here because the country’s sole aircraft carrier, the Charles de Gaulle, has been in the shop for repairs and renovations since 2017. So the pilots have been practicing aboard one of US Navy’s 11 aircraft carriers in what has been dubbed Operation Chesapeake -- a reference to the 1781 battle during the US War of Independence when the French fleet, allies of the new country, dealt a blow to the British in a key encounter that turned the tide of the war.

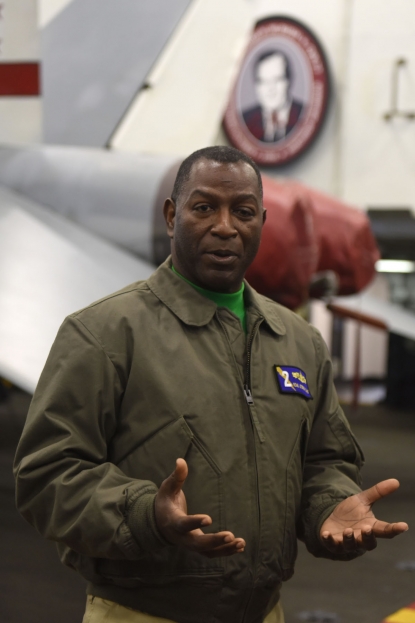

Former US president George HW Bush is watching -- Rear admiral Stephen Carl Evans speaks to journalists in front of a portrait of the former president aboard the aircraft carrier that bears his name.

(AFP / Eric Baradat)

Former US president George HW Bush is watching -- Rear admiral Stephen Carl Evans speaks to journalists in front of a portrait of the former president aboard the aircraft carrier that bears his name.

(AFP / Eric Baradat)I was particularly interested in covering this exercise -- as a former Pentagon correspondent currently covering the French armed forces, I was curious to see how the two allies, each with such distinctive styles and cultures, would cohabitate and get along within the confined spaces of a floating city.

We receive a warm, laid-back welcome. “You can talk to whoever you want and photograph pretty much anything you want, or nearly so” a spokesman for the US Navy tells us. Culture shock number one -- French defense reporters are used to having to operate under much stricter rules -- you can’t name troops, you have to blur pilots’ faces and PR people keep a sharp eye on what the soldiers tell us.

Before we’re let loose, we pay the obligatory visit to the Tribute Room, a room on each aircraft carrier that pays homage to its namesake, in this case George Bush senior, the United States’ 41st president who served from 1989 to 1993.

Bush was himself a Navy pilot who fought in the Pacific during World War II at the tender age of 18, the youngest US Navy pilot ever. In 1944 he was shot down and rescued by a US submarine. The rescue, which was filmed by a crew member, is part of the collection, along with official and family photos that plaster the walls.

When we get back on deck, the place is abuzz with activity, with fighter jets about to take off. We immediately notice a catapult officer -- one of those guys with yellow jackets that direct plane traffic on deck -- dancing as he he sends an F-18 into the air, just like in the movie Top Gun. “I like to have fun, I put a little bit of style in it", Nigel tells me later, loudly laughing and showing off.

I glance at Bruno, the chief of the French catapult officers. “We are a bit more sober,” he deadpans. He demonstrates the gestures used by the French to send the planes off -- they’re practically identical to the American ones, minus the groove. Culture shock number two.

Catapult officer Nigel (R) gestures as a French Navy Hawkeye surveillance plane is catapulted off the USS George H.W. Bush aircraft carrier on May 11, 2018 in the Atlantic Ocean.

(AFP / Eric Baradat)

Catapult officer Nigel (R) gestures as a French Navy Hawkeye surveillance plane is catapulted off the USS George H.W. Bush aircraft carrier on May 11, 2018 in the Atlantic Ocean.

(AFP / Eric Baradat) Le Catapult officer Nigel (L) gestures as a US Navy F/18 Hornet jet is catapulted off the USS George H.W. Bush aircraft carrier on May 11, 2018 in the Atlantic Ocean. (AFP / Eric Baradat)

Le Catapult officer Nigel (L) gestures as a US Navy F/18 Hornet jet is catapulted off the USS George H.W. Bush aircraft carrier on May 11, 2018 in the Atlantic Ocean. (AFP / Eric Baradat)

The navies of the two NATO allies know each other well and have participated in countless joint operations over the years. The French say that the pace is a bit more intense on a US carrier.

“Our challenge is the intensity and the speed” of the manoeuvres, a French pilot tells me.

“One of the major differences between us is scale. The Charles de Gaulle launches all the planes and then recovers them. We can do both at the same time. We operate at a higher rate” Commander Steven Thomas, the second in command, tells me. His official title is “Air Boss” and he wears a T-shirt emblazoned with it, as well as a smaller “mini boss,” to distinguish that he is not the top dog. Culture shock number three -- the French would never wear a self-deprecating T-shirt that pokes fun at their rank.

Air Boss at work in the Island (the control tower) of the USS George H.W. Bush aircraft carrier on May 11, 2018 in the Atlantic Ocean.

(AFP / Eric Baradat)

Air Boss at work in the Island (the control tower) of the USS George H.W. Bush aircraft carrier on May 11, 2018 in the Atlantic Ocean.

(AFP / Eric Baradat)Part of the reason for the difference in intensity onboard is size -- the Charles de Gaulle is 260 meters long and it’s physically impossible to have planes taking off and landing at the same time. The USS George HW Bush is 333 meters long (or like the PR materials say, "almost as long as the Empire State Building is high"), with four catapults.

The differences between the two militaries are easy to see when you compare the figures.

In 2018, Washington will spend some 700 billion dollars on defense; Paris will spend less than half that…. over the course of the next eight years.

Not that size is everything, the French will quickly point out.

“The Bush is more than twice as large as our aircraft carrier. It’s longer, so in a way, it’s easier to land on the Bush than on the Charles,” the French Navy Chief of Staff, Admiral Christophe Prazuck makes sure to tell me.

The flight deck.

(AFP / Eric Baradat)

The flight deck.

(AFP / Eric Baradat)In the mess hall, the menu for the evening includes ribs, fried chicken, fries, vegetables, ice cream. There are vending machines with salty and sugary snacks. Soda is freely available, alcohol is nowhere in sight.

“The food here is much greasier,” sighs a tall Frenchman, looking sadly at his tray. Culture shock number four. The French aircraft carrier, like the rest of the country’s armed forces, are famed for their excellent cuisine, including fresh baguettes and croissants. American cities may boast excellent restaurants but the culinary tradition has yet to trickle down to its troops.

When it’s time to go to bed, the din of the ship hasn’t yet died down -- life aboard an aircraft carrier goes on day and night. My cabin is part of a row of VIP cabins named after posts held by George HW Bush -- “CIA Director,” “Ambassador to China,” “US President.”

The dark blue bed sheets feature the ship's seal. There are several books on World War II and a biography of Bush Sr by his daughter, “My father, my president.” (Apparently within the Bush family, the aircraft carrier is known as “USS Dad”).

A F/18 Hornet is catapulted from the deck of the USS George H.W. Bush aircraft carrier on May 11, 2018 in the Atlantic Ocean. (AFP / Eric Baradat)

A F/18 Hornet is catapulted from the deck of the USS George H.W. Bush aircraft carrier on May 11, 2018 in the Atlantic Ocean. (AFP / Eric Baradat)At 10:00 pm, a prayer is transmitted over the PA system. Culture shock number five -- the French have been raised in a country where religious practices are kept out of public spaces (though the vast majority of public holidays are Catholic). The US is a country where the first settlers came so that they could practice their religion in peace and where the president takes the oath of office with his hand on a Bible, so a public prayer is nothing out of the ordinary.

“The evening prayer is an old tradition,” chaplain John Logan, one of four chaplains aboard the USS Bush, tells me the next day. But “we avoid praying in the name of Jesus. We preach a general message everybody can connect to.”

A catapult officer gestures as a US Navy F/18 Hornet jet is catapulted off the USS George H.W. Bush aircraft carrier on May 11, 2018 in the Atlantic Ocean.

(AFP / Eric Baradat)

A catapult officer gestures as a US Navy F/18 Hornet jet is catapulted off the USS George H.W. Bush aircraft carrier on May 11, 2018 in the Atlantic Ocean.

(AFP / Eric Baradat)