The last Nazi trials

Detmold, Germany -- “A semblance of justice.” The four words fall like thunder in the courtroom, where a judge has just used them to describe her verdict. “There is no adequate sentence for such atrocious actions,” Judge Anke Grudda says in a clear voice amid the tense silence.

The court in this western German city has just sentenced 94-year-old Reinhold Hanning to five years in prison. The former SS officer has been convicted of contributing to the murder of at least 170,000 men, women and children during his two and a half years at the Auschwitz death camp.

He walked into the courtroom for the start of his trial in February but listens to the verdict in a wheelchair. His trial, as well as that of Oskar Groening, known as the “book-keeper” of Auschwitz who was sentenced in July 2015 to four years in prison for his role in the death of 300,000 Hungarian Jews, are likely to be the last of the Nazi trials.

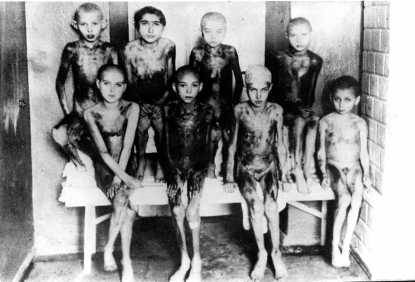

Children of death camp survivors as shown in the film Auschwitz by Soviet filmmaker Elizaveta Svilova in 1945.

(AFP / Elizaveta Svilova)

Children of death camp survivors as shown in the film Auschwitz by Soviet filmmaker Elizaveta Svilova in 1945.

(AFP / Elizaveta Svilova)The two trials had an air of contradiction that I never managed to describe in my dispatches for AFP. In Lunenburg and Detmold, judges handed out sentences that are unlikely to be served in full. The justice system recognized the guilt of the few cogs of the Nazi machine, but most of them have long gone. Old men were put on trial, 70 years after the death camps were liberated, while their bosses had been left alone for years. Out of the 6,500 Auschwitz guards who had survived the war, less than 50 have been sentenced. A pathetic statistic that German justice is trying to belatedly set right.

The paucity of debate on this subject in Germany is striking. Judges here have long held that justice for the Holocaust must be carried out to the end. But this determination at times results in uneasy images. Like when a court last year ruled that 95-year-old Hubert Zafke was “not totally inept to appear” in the courtroom. Or when 93-year-old Ernst Tremmel died a week before he was to be judged -- under juvenile law because of his age at the time of the acts. Or when 90-year-old John Demjanjuk was convicted in Munich in 2011, a mute drooling in his chair.

John Demjanjuk, accused of being a guard at a Nazi death camp Sobibor, arrives in a wheelchair for another day of his trial in the courtroom in Munich on March 17, 2011. (AFP / Sebastian Widmann - pool)

John Demjanjuk, accused of being a guard at a Nazi death camp Sobibor, arrives in a wheelchair for another day of his trial in the courtroom in Munich on March 17, 2011. (AFP / Sebastian Widmann - pool)Demjanjuk’s trial was a turning point in the Nazi trials, as the former Sobibor guard was convicted without prosecutors having proved that he actually killed anyone. In previous trials, starting with the Nuremberg trials of 1945, prosecutors had to prove the defendant’s direct involvement in atrocities. But since Demjanjuk’s trial (he died pending appeal), it has been sufficient to prosecute someone for being a cog in the machine.

The Nazi trials of the past several years have been a race against time -- both the accused and the victims are octogenarians and higher. Much of the testimony of these trials consists of survivors recounting their tales, the most heart-wrenching accounts that I have ever heard. But for the most part, they do not mention the accused, because most victims don’t remember having seen them in the camps. In the immensity that was Auschwitz, the SS guards rest a mass of black and green-gray uniforms, not men that survivors remember.

“Do you have any good memories of any SS guards? Did some behave better than others?” the judge asks the first survivor witness during the Hanning trial.

“I have to say no. I don’t have any memories like that. I lived in constant terror,” answers 95-year-old Leon Schwarzbaum, who lost 35 members of his family in the Holocaust.

Auschwitz survivor Leon Schwarzbaum attends a session of a trial against former Auschwitz guard Reinhold Hanning at a court in Detmold, Germany, on April 29, 2016. (AFP / Bernd Thissen)

Auschwitz survivor Leon Schwarzbaum attends a session of a trial against former Auschwitz guard Reinhold Hanning at a court in Detmold, Germany, on April 29, 2016. (AFP / Bernd Thissen)The prosecution files in these trials are surprisingly small -- during the Groening trial, the evidence of the destruction of 300,000 lives in two months fit into three plastic crates. That’s less than your average organized crime trial, during which the prosecution produces tomes and tomes of evidence.

Contrary to the first Nazi trials, establishing the facts of the Holocaust is no longer a requirement, as historians have documented the horrors. The testimonies of both the accused and the victims do not diverge when they describe what happened in the death camps. They may differ on the perspective, but they are in agreement on the brutality of the acts -- the disappearance within seconds of loved ones in the gas chambers, after a doctor decided they weren’t fit enough for work or other purposes.

Every story you heard at these trials was different. My colleague Hui Min Neo poignantly told the story of Angela Orosz, a petite woman who came from Canada to testify. She was born in Auschwitz and was one of the few babies to have survived the camp, saved by her mother and a handful of her co-detainees. All victims deserve such a heartfelt rendering and it’s a shame that they didn’t get one.

Angela Orosz who was born in Auschwitz shows a photo of her parents wedding guests, during the Hanning trial. (AFP / Friso Gentsch - pool)

Angela Orosz who was born in Auschwitz shows a photo of her parents wedding guests, during the Hanning trial. (AFP / Friso Gentsch - pool)I would have liked to have described the emotion evoked by Erna de Vries, her soft features and her calm voice. The 17-year-old student dreaming of becoming a doctor was taken in a raid, but then released because she was only half-Jewish. She went home, packed a suitcase and returned voluntarily, to accompany her mother to Auschwitz. Before her mother died, she made her daughter promise that she would survive so that she could tell the world about what she saw. Erna did so in the courtroom, surrounded by her family, her hand cupping that of her granddaughter.

Leon Schwarzbaum told of having grown up in a Polish Yiddish community and of his father, who refused to fear the Germans, “these people of poets and philosophers.” But only 50 kilometers separated the Bendzin ghetto where he lived from Auschwitz and when he was finally deported to the camp in August 1943, “we had an idea of what was happening. Some parents tried to throw their children off the train.”

A photo taken sometime between 1940 and 1945 in Auschwitz shows naked children, apparently after medical experiments. (AFP)

A photo taken sometime between 1940 and 1945 in Auschwitz shows naked children, apparently after medical experiments. (AFP)To hear descriptions of the camps from victims is heart-wrenching. To hear them from the jailers is disconcerting to say the least. Hanning wrote a 25-page confession in which he speaks both of the smell of the crematoriums and the deplorable "lack of camaraderie” among the soldiers.

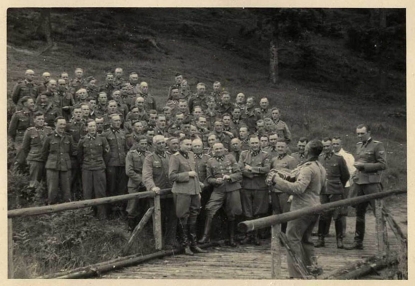

SS officers at a social gathering near Auschwitz, date undetermined.

(AFP / Holocaust Memorial Museum)

SS officers at a social gathering near Auschwitz, date undetermined.

(AFP / Holocaust Memorial Museum)Groening is different. Haunted by Auschwitz since his retirement thirty years ago, he didn’t wait for the justice system to catch up to him. He has written a memoir, participated in documentaries and books, has endured threats and insults and opened his door to journalists several months before his trial.

“Are you ready to answer,” the judge asked him during his trial, reminding him that he had a right to remain silent.

“As long as I can,” came the reply.

Oskar Groening at his trial.

(AFP / Ronny Hartmann)

Oskar Groening at his trial.

(AFP / Ronny Hartmann)He gulped his bottle of water in one go -- “Like vodka in Auschwitz”-- and plunged into an incredibly detailed and dense testimony. He was at turns prosaic and terrifying, at times showing what seemed like sincere repentance and then saying things that revealed just how deeply Nazi propaganda had infiltrated his thoughts.

Like many of the accused before him, he could have said that it was impossible not to follow orders in a dictatorship. But Groening didn’t hide that he was “euphoric” in the first hours of the war, and that he then joined the project to kill “the enemies of the German people.” You realized the extent of his indoctrination when he spoke of the Holocaust as the “war effort” or when he described the “routine” preparations for exterminate Hungarian Jews.

Coming from a man who was tormented by his conscience and opposed to violence to the point of “never having slapped anyone in my life,” his testimony is not easily forgotten.

A pile of human bones and skulls is seen in 1944 at the Nazi concentration camp of Majdanek in the outskirts of Lublin, the second largest death camp in Poland after Auschwitz, following its liberation in 1944 by Russian troops. (AFP)

A pile of human bones and skulls is seen in 1944 at the Nazi concentration camp of Majdanek in the outskirts of Lublin, the second largest death camp in Poland after Auschwitz, following its liberation in 1944 by Russian troops. (AFP)Some may ask the point of telling these personal tales, when historians have dissected the Holocaust in every imaginable way.

“To understand that Auschwitz did not happen on Mars,” says Andrej umansky, a historian, lawyer and specialist in German law. “Personal connections make it less abstract and do away with the idea that it can never happen again.”

Jewish women and children get off trains at Auschwitz during World War II. (AFP / Stf)

Jewish women and children get off trains at Auschwitz during World War II. (AFP / Stf)Throughout these two trials, the public benches were always filled, even when those for the press emptied as the days dragged on. There were the relatives of the victims and just observers, equally divided between men and women, many university and high school students among them. Looking at their tense faces and eyes red from tears of some, I got the impression that they will not forget.

Participants of the annual "March of the Living" at Auschwitz in May, 2016.

(AFP / Wojtek Radwanski)

Participants of the annual "March of the Living" at Auschwitz in May, 2016.

(AFP / Wojtek Radwanski)