Frankie goes to Hollywood

LOS ANGELES - "I'm sorry, no. There's a mistake. 'Moonlight' -- you guys won best picture."

?????

"This is not a joke, come up here. This is not a joke. 'Moonlight' has won best picture.”

???!!!!!!

'Moonlight': best picture."

!@!#@$!@@%^$!!!

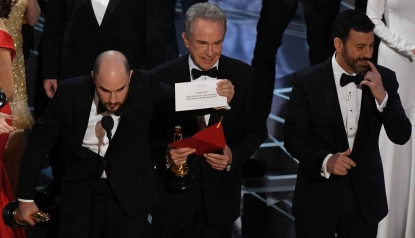

"This is not a joke.... Moonlight: best picture." La La Land producer Jordan Horowitz shakes up the Oscars.

(AFP / Mark Ralston)

"This is not a joke.... Moonlight: best picture." La La Land producer Jordan Horowitz shakes up the Oscars.

(AFP / Mark Ralston)A pyroclastic, R-rated eruption of sulfurous invective almost blew over my computer screen as my colleagues and I tried to make sense of what was going on. We were covering the biggest show business event of the year, the Oscars, and had just witnessed the earthquake announcement -- the wrong film had been named as best picture. Moonlight was due the glory instead of La La Land.

(AFP / Gabriel Bouys)

(AFP / Gabriel Bouys)B-b-but they just said "La La Land" was the winner. They can't change it now. Can they?

It can have escaped no one -- not the remote hill tribes of the Himachal Pradesh, not even Warren Beatty, bless him -- that Damien Chazelle's joyfully shallow paean to the self-absorbed banality of Hollywood was wrongly announced as the best picture winner at this year's Oscars.

When the mistake was realized, we bounced around the newsroom like popcorn in a skillet, trying to figure out who to blame for this shocking but undeniably thrilling gaffe.

Would heads roll? Was Putin involved? Would Trump send troops into Hollywood Boulevard? Had someone told the new chap at the UN?

It all made for a rather fittingly surreal denouement to a dreamlike first year in my latest AFP posting, covering the entertainment industry from our Los Angeles bureau on Sunset Boulevard.

A little over 12 months earlier, the first day of the rest of my life had hardly gone as expected either.

Newly arrived in board shorts and flip flops in anticipation of that famous southern California sunshine, I was greeted by a rare cold snap and was drifting into a hypothermic coma in the unheated lobby of an immigration and customs office near the airport.

Southern California as it usually is.

(AFP / Frederic J. Brown)

Southern California as it usually is.

(AFP / Frederic J. Brown)I had come to secure the release of Biggie and Tupac, who were shivering forlornly from behind bars in the holding pen, naked as the day they were born.

Papers in order, I hailed a taxi and cleared off the back seat for my companions, whom I should probably say are West African domestic short-haired cats, and not iconic hip hop artists gunned down in tit-for-tat murders at the height of the East-West Coast gangsta rap rivalry of the 1990s.

When the job of entertainment correspondent came up, I'd had my doubts.

Some friends expressed surprise that I was giving up serious journalism, while one cynical acquaintance from a London tabloid congratulated me on finally deciding to write stories that people might actually read.

After a hectic few months of acclimatization, however, it became obvious I had the best job in journalism. They pay you to go to the cinema!

They pay you to do this when you're LA correspondent.....

(AFP / Anne-christine Poujoulat)

They pay you to do this when you're LA correspondent.....

(AFP / Anne-christine Poujoulat)So what does the best job in journalism actually entail?

The basics are obvious: you write about TV shows and movies that people might be interested in, interview the people who make them and pretend to be out when the newsdesk in Washington calls about one of the Kardashians.

I'd be lying if I said it was significantly more complicated than that (note to news desk -- I was out).

I'm often asked -- once by an incredulous Hugh Grant -- if it was weird transferring from writing about jihadist conflict and Ebola in west Africa, or the amorphous politics of Nepal, to covering the rich and famous.

From covering jihadist threat during elections in Mali.....

(AFP / Kenzo Tribouillard)

From covering jihadist threat during elections in Mali.....

(AFP / Kenzo Tribouillard) To covering Hugh Grant.

(AFP / Eli Gorostegi)

To covering Hugh Grant.

(AFP / Eli Gorostegi)

But journalism is a transferable skill, and a large proportion of entertainment reporting is just like any other type of coverage.

A Led Zeppelin plagiarism lawsuit or Johnny Depp divorce case is just court reporting. A Q&A with the cast of "Game of Thrones" is really no different from a parish council meeting.

An interview with a veteran director or movie star is no easier or trickier than interviewing a politician.

(Aside: the best access I've ever had to a former or incumbent head-of-state was a long interview with ousted Maldives leader Mohamed Rasheed -- at the Sundance Film Festival.)

There are several ways of getting yourself in front of the stars and one of the most common, and most frustrating, is the red carpet.

The frustrations of the red carpet.

(AFP / Antonin Thuillier)

The frustrations of the red carpet.

(AFP / Antonin Thuillier)You can probably picture the scene, even if you've never attended a celebrity event in your life: several dozen photographers, video teams and text journalists clamoring frantically for soundbites like blind infant mole rats wrestling at the teat at feeding time.

Red carpets demand stamina and strong elbows. You are given a space so narrow only a two-dimensional lifeform could keep within his allocated boundaries.

You are forced to turn up at least an hour before the action gets going. If it's an awards show or gala dinner you are wearing a tuxedo and the sweat from your neck is starting to pool in your shoes.

For the first 58 minutes, the majority of people passing by are less famous than you -- the kid who had a non-speaking role in a scene that was cut, the second cousin of the catering supervisor.

The rare genuine star that does pass by doesn't feel like talking and is trying simultaneously to feign deafness while breaking the land speed record.

And then in the last two minutes comes the rush, when the entire A-list is shoved suddenly onto the overcrowded carpet like Serengeti wildebeest being coaxed onto a subway train. Try getting a worthwhile quote out of that lot.

Did he just say a good quote? George Clooney with his wife Amal Alamuddin on the red carpet at the Berlinale in Berlin, February, 2016. (AFP / John Macdougall)

Did he just say a good quote? George Clooney with his wife Amal Alamuddin on the red carpet at the Berlinale in Berlin, February, 2016. (AFP / John Macdougall)A much easier way of getting face-time with the famous is the movie junket, a little-understood aspect of entertainment coverage that involves film studios promoting their latest release by bringing journalists and talent together in one spot to make magic.

There are different types of junket but the ones I get invited to are typically gatherings of the international press, almost always in a posh hotel in Beverly Hills.

You arrive, you check in outrageously early, and you wait, often for a long time, as the delays inevitably pile up.

This, as it happens, is no hardship. Journalists at junkets are invariably fed and watered at lavish buffets that make the epicurean excess of Nero's orgies look like the tightfisted apotheosis of prudent budgeting.

That's a Grilled Eggplant with Sundried Tomato and Pine Nut Hummus on Seared Tomato Mini Sweet Pepper with Feta Cheese Pomegranate Herbs California Olive Oil on Grilled Pita Grilled Artichoke on Multigrain Tabbouleh and Tahini. (AFP / Joe Klamar)

That's a Grilled Eggplant with Sundried Tomato and Pine Nut Hummus on Seared Tomato Mini Sweet Pepper with Feta Cheese Pomegranate Herbs California Olive Oil on Grilled Pita Grilled Artichoke on Multigrain Tabbouleh and Tahini. (AFP / Joe Klamar) And that's a Gusto Mango dessert on Almond Sponge Cake with Creme Anglaise to top it off.

(AFP / Joe Klamar)

And that's a Gusto Mango dessert on Almond Sponge Cake with Creme Anglaise to top it off.

(AFP / Joe Klamar)

If you are lucky, you have been offered some one-to-one time with the lead actor or actress of the big summer blockbuster.

Just as often, you are participating in roundtable interviews with an obscure screenwriter or producer and seven other journalists, each of whom has their own angle or agenda.

He's as likeable as you think he is... (AFP / Tommaso Boddi)

He's as likeable as you think he is... (AFP / Tommaso Boddi)Good journalists come to this kind of situation armed with a question or two that may elicit a controversial, topical or otherwise newsworthy response from a hopefully outspoken actor.

Often you raise your hand but your question ends up going to a blogger who wants to know what designer the star prefers, what they last ate, or if they have a message for the people back home in Papua New Guinea.

One-to-one time with the biggest names can, of course, be an enriching experience.

While they are contractually obliged to promote their films, they aren't required to be polite or charismatic, and it is surprising how often they are.

Hugh Grant was disarmingly honest, and while admitting he sometimes found press interviews excruciating, was the epitome of charm throughout.

Russell Crowe made fun of my English accent -- which is a bit rich, given his undeniably Irish delivery of the West Midlands dialect in Ridley Scott's "Robin Hood" -- but he was only having fun.

Elijah Wood, Jon Favreau, Bryce Dallas Howard and Zoe Saldana were opinionated and engaging, and Christoph Waltz was combative, but funny and insightful.

I've met Tom Hanks a couple of times and he is as charismatic and lovely as you'd probably expect.

Even when it's obvious the star in front of you hated the movie they are promoting, they can still be fun to interview.

Samuel L Jackson talked passionately about European colonialism and the Atlantic slave trade, probably keen not to be questioned too deeply on what he thought of the woeful "The Legend of Tarzan."

Morgan Freeman, who must have known how bad "Ben Hur" was, gave professional answers to the questions about his character but was more interested in flirting outrageously with a young reporter dressed in ripped jeans.

Actress Tea Leoni greets Morgan Freeman, executive producer of the new television series Madam Secretary, at the show's premiere in Washington on September 18, 2014. (AFP / Nicholas Kamm)

Actress Tea Leoni greets Morgan Freeman, executive producer of the new television series Madam Secretary, at the show's premiere in Washington on September 18, 2014. (AFP / Nicholas Kamm)Not all stars are easy to interview, of course.

Linda Blair, the iconic demon child in "The Exorcist," didn't much want to talk about her only famous role and interpreted every question as an invitation to bang on about her dog rescue charity.

Kate Mara answered questions politely but looked bored and played with her phone during a 15-minute meeting paired with Anya Taylor-Joy, her co-star in the horror film "Morgan."

It's rare that stars are rude, however, and from my first year in Hollywood I have identified four more common reasons for interviews going awry.

The first is that you -- the journalist -- just didn't bring your 'A game' to the encounter. Your questions were dull or you didn't succeed in striking up a rapport with your subject. You have to accept the blame when that happens. It's a big part of the job.

The second is time, or rather the lack of it. There really is surprisingly little ground you can cover in a ten-minute interview and sometimes, especially at the end of the day, you get even less than that.

The friendlier stars sometimes treat the interview as a conversation, taking up two or three of your precious minutes asking if you want a soda, commenting on how they like your accent, or asking you about your background.

Then they might expound at length on your ice-breaker question, the one you have no intention of using. Suddenly you're staring at a notebook with 10 well-researched, incisive questions and only three minutes left to get through them.

Grammy Award-winning rapper and founder of the hip-hop group The Fugees, Pras Michel, poses following an interview with AFP in Los Angeles, California, on June 11, 2015, where his film Sweet Mickey for President premieres at the Los Angeles Film Festival. (AFP / Frederic J. Brown)

Grammy Award-winning rapper and founder of the hip-hop group The Fugees, Pras Michel, poses following an interview with AFP in Los Angeles, California, on June 11, 2015, where his film Sweet Mickey for President premieres at the Los Angeles Film Festival. (AFP / Frederic J. Brown)The over-zealous publicity person is the third and most annoying potential spanner in the works. This is the voice in your ear who wants to shepherd the conversation in a particular direction and complains when you go off topic.

It would be imprudent to name names, but I remember interviewing one legend of horror filmmaking -- let's call him Freddy. Or Jason, let's call him Jason.

So Jason had been put in front of me to publicize a product than no one outside of southern California would have much interest in -- let's say it was a new Los Angeles-based Mexican food chain.

But Jason is an icon to genre fans the world over and has a hundred amazing stories about the movies he has made.

Every time the conversation strayed to his back catalogue, the voice behind me would interrupt: "Can we please get back to the burritos?"

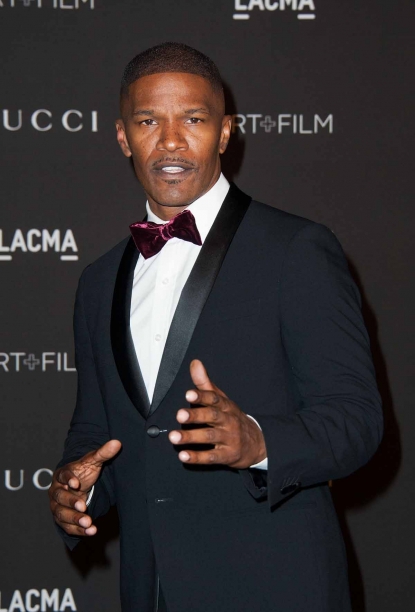

Actor Jamie Foxx in 2014. (AFP / Valerie Macon)

Actor Jamie Foxx in 2014. (AFP / Valerie Macon)A final problem with junket interviews is the stars who just aren't quotable. It's not uncommon to encounter an actor who doesn't finish a single sentence, let alone a coherent line of argument.

You come away thinking you had an intriguing discussion about practical aesthetics or the Lee Strasberg Method, but you transcribe the tape and what you actually have is a half-wit clumsily chasing trains of thought like they are balloons with the air let out.

A subset of these unquotable stars is the profane celebrity -- the sweary Mary, the potty-mouthed Pete -- who can't utter a single sentence without deploying the oedipal expletive.

I had to limit my interview with the charming Jamie Foxx to just a couple of direct quotes because every time he gave flight to some amusing anecdote he'd machine-gun it down with a volley of f-bombs.

It felt more like we were sharing a scene in a Tarantino movie than taking part in an interview.

It has taken me a year, but I'm starting to get to know my way around town and I'm looking forward to staying here a good while before getting back to the real world and a job where sneaking off to the cinema in the afternoon is a sackable offense.

(AFP / Mladen Antonov)

(AFP / Mladen Antonov)To my eventual successor I would offer the following advice:

(1) Pack something warm. Angelenos boast about their 300 days of sun. If you arrive in February, 65 days of rain will unload on your head in the first week. In the second week you will be badly sunburned;

(2) If you have a junket to go to, skip breakfast. But don't let that lobster thermidor undermine your integrity or independence;

(3) You will be unnerved by the nagging suspicion that you've met every single barista and Uber driver somewhere before. You haven't. They were Man with Chicken Quesarito in the Taco Bell commercial you just watched;

(4) This is the most important. When they announce the Oscar for best picture, close your eyes and count to ten. If the world hasn't ended in fiery armageddon by the time you open them, you're probably safe to send that alert.

The lights of the city of angels. (AFP / Joe Klamar)

The lights of the city of angels. (AFP / Joe Klamar)