‘Journalist scum’ and the Cannes glitterati

CANNES, France, May 26, 2015 - Two floors above us is an impossible level of glamour, people of such mind-bending charisma that the mere sight of them walking on carpet can set off a frenzy of shutter clicks and hysterical screaming.

But pan down through the floors into the basement, and things are decidedly less glamorous: long corridors hastily constructed from some kind of off-white plyboard, unmarked doors that open to swarming nests of journalists tripping over cables and crammed around banks of wonky screens, frantically relaying the upstairs glitz to a ravenous public.

Marion Cotillard, after a screening of 'The Little Prince' at the Cannes Film Festival on May 22, 2015 (AFP Photo / Loic Venance)

Marion Cotillard, after a screening of 'The Little Prince' at the Cannes Film Festival on May 22, 2015 (AFP Photo / Loic Venance)Occasionally, we leave "the bunker" to discover the sun is beaming down on the Cote d’Azur, but our pasty skin barely has time to glug down a little Vitamin D before we are hustling our way into a darkened cinema.

A speck in the filthy horde

It is my first time at the Cannes Film Festival, and I am deliriously happy at the sight of my pink press pass. It signifies my position fairly high on the colour-coded social hierarchy, able to saunter smugly past long lines of wretches who look like they have been waiting for weeks.

Yet in comparison with the glittering ubermensch of the red carpet, I am still just another speck in the filthy horde. From the perspective of the 500-foot yachts parked offshore, my pink pass raises my status only from "scum" to "journalist scum". Not only am I denied entry to the cool parties, I don't even know they're happening until they're over.

Festival-goers posted on stepladders for a glimpse of the action at the Cannes Film Festival on May 14, 2015

(AFP Photo / Valery Hache)

No doubt out of bitterness, I start to recoil slightly at the weird contradiction that lurks at the heart of the festival. The world of plasticised excess that parades around in the sunlight seems to bear an almost obscene lack of connection with the art and emotion that happens in the darkness of the theatres. One minute we are gawping at the absurd truckload of diamonds shovelled on to Jane Fonda's neck, and the next we are watching a bleak French drama about a laid-off factory worker desperately looking for a job.

US writer-producer Chris Sparling and actors Naomi Watts and Matthew McConaughey arrive for the screening of 'The Sea of Trees' in Cannes on May 16, 2015 (AFP Photo / Bertrand Langlois)

US writer-producer Chris Sparling and actors Naomi Watts and Matthew McConaughey arrive for the screening of 'The Sea of Trees' in Cannes on May 16, 2015 (AFP Photo / Bertrand Langlois)Naomi Watts shows up on the carpet. She gets just a few seconds in front of a camera, but somehow manages to crowbar in the name of the cosmetics company for which she is an "ambassador".

Aggressive capitalism and high art

This concept astonishes my naive mind. I had no idea make-up issues had been elevated to the level of international diplomacy. Will she assume these ambassadorial functions at the United Nations, too? Perhaps Angela Merkel will table a motion on reversing the signs of ageing.

I'm relieved to find I'm not alone in finding this juxtaposition of aggressive capitalism and high art a little difficult to stomach. A few days in, I interview director Asif Kapadia who is presenting his masterful tear-jerker documentary "Amy" about late singer Amy Winehouse. "It's a bit weird", he says, to appear before a mass of flashbulbs for a film that savages the role of the paparazzi.

Emily Blunt and Benicio Del Toro arrive on a television set on the sidelines of the Cannes Film Festival on May 20, 2015

(AFP Photo / Bertrand Langlois)

Still, the allure of the stars will not be denied. I am no more immune to the excitement of being five metres away from Emily Blunt and Benicio Del Toro at a press conference than anyone else. Faced with a certain level of fame, we all become slack-jawed stalkers, staring unblinkingly at the glittering creatures, laughing too hard at the merest hint of a joke, blushing dramatically if they so much as grimace in our direction.

Actor and jury member Jake Gyllenhaal at a press conference in Cannes on May 13, 2015 (AFP Photo / Loic Venance)

Actor and jury member Jake Gyllenhaal at a press conference in Cannes on May 13, 2015 (AFP Photo / Loic Venance)Or maybe I don't care at all. Perhaps I have just been conditioned by the relentless Hollywood PR juggernaut to believe I am obsessed with these people. On my third day, I practically collide with Jake Gyllenhaal in the street. I double-take and reach for my notebook but he is moving like hunted prey and quickly disappears.

Brush with megastardom

I stare after him and perform an internal scan to see what impact this brush with megastardom has had on my feeble commoner's body. I assume my blood has been rejuvenated, my eyeballs whitened, my antibodies strengthened. But after a moment, I have to admit I don't feel much of anything and continue on my journey to buy a cold croque monsieur from the supermarket.

Cate Blanchett attends a photocall for the film 'Carol' in Cannes on May 17, 2015 (AFP Photo / Loic Venance)

Cate Blanchett attends a photocall for the film 'Carol' in Cannes on May 17, 2015 (AFP Photo / Loic Venance)Once in the cinema, everything seems to make sense. Everyone shuts up and watches. It's genuinely exciting. Most of these films have never been shown in public before. With no trailers or publicity ahead of time, we have absolutely no preconceptions, almost as if these events are unfolding in real time, heightening the shock of both greatness and failure.

Cinema's magic and breadth

There is emotion in these cinemas that doesn't exist elsewhere - people burst into applause after the action sequences in "Mad Max: Fury Road" or the final, fizzing moment in lush lesbian love story "Carol". They boo like baying donkeys at the shockingly bad "The Sea of Trees" with Matthew McConaughey.

Sean Penn and his partner Charlize Theron arrive for the screening of 'Mad Max: Fury Road' in Cannes on May 14, 2015

(AFP Photo / Valery Hache)

At one point, the exterior crassness breaches the walls of the theatre, when shockmeister Gaspar Noe presents his ultra-explicit 3D movie "Love" at a midnight screening. It promises the requisite dose of controversy that each Cannes requires, so every journalist and rubbernecker on the French Riviera tries to get in, only to realise they have condemned themselves to two hours of seeing - both literally and figuratively - a penis ejaculating into their faces. In three dimensions.

But for the most part, the experience of covering the Cannes Film Festival is a terrific reminder of cinema's magic and breadth. I became a father nearly a year ago, and have barely been able to visit a cinema since. In 12 days, I have made up for it many times over. I have seen water-dragons slain in 16th-century Italy, scurried through drug-trafficking tunnels on the US-Mexico border and watched Michael Caine conduct a field of cows. I have become utterly lost in the bubble of cinemaland. I am left bewildered and disoriented. I no longer know what is happening in the real world, and I no longer want to.

Eric Randolph is an AFP reporter based in Paris

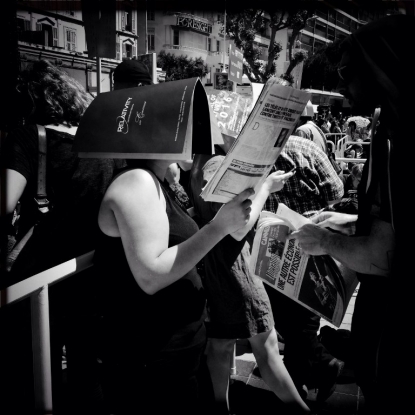

A woman shields herself with a film trade magazine during the Cannes Film Festival on May 16, 2015 (AFP Photo / Valery Hache)

A woman shields herself with a film trade magazine during the Cannes Film Festival on May 16, 2015 (AFP Photo / Valery Hache)