About Brexitime for an independent Scotland

Hong Kong -- After 30 years living abroad as an expat Scot I’d managed to more or less figure out my family’s place in the world. Or at least that was the case until Brexit came along.

Born in Glasgow, Scotland, I joined AFP in Paris in 1984, married an American and we had two children -- who went to French schools and speak the language fluently. The family has strong bonds to the United States and Britain and also to our adopted homes of France and more recently Hong Kong. Ask us where we all come from and you will not get a very clear answer, but at least there were some anchors out there.

My accent – you can take the man out of Glasgow but you can’t take Glasgow out of the man – certainly anchors me in Scotland.

Our home in France and our European identities were other anchors.

But the Brexit result last week effectively sent us heading into uncharted waters, particularly for my (adult) children, who spent much of their childhood in France but who have British and US passports. While their British passports used to be European passports, this will no longer be the case.

(AFP / Leon Neal)

(AFP / Leon Neal)My more than 30-year career at AFP is without a doubt the thing that anchors our family most firmly to France and to Europe. We had always planned to apply for French citizenship, but gathering together all the necessary official documents from administrative authorities in the UK, Ireland and various cities in the United States has been a long and frustrating process: by the time a certified copy of one parent’s birth certificate was issued by the Registration of Persons Bureau in Omaha, Nebraska, the birth certificate we had obtained from Scotland for another parent would be past the three month validity limit imposed by the French administration.

Fortunately, with most of the family on British passports, we were free to live in France and anywhere else in Europe, and we could not have imagined in a lifetime of French Sunday lunches that this would ever change.

So with a sudden sense of being cut adrift from our French and European cultures by the referendum result, my ears ringing and head spinning in shock, and after a lifetime of rejecting the very notion of Scottish independence, I posted this on my Facebook timeline in the seconds following the result: “I’ve just become a supporter of Scottish independence – for real”.

That famous quote from George Bush Senior (and the Big Lebowski) flashed through my mind as I did it: “This aggression will not stand”.

And this is from someone who deeply believes in the United Kingdom and its shared history and values.

But what choice did I have -- after Scotland had chosen overwhelmingly to remain in the European Union, it saw its future decided otherwise by voters in the English heartlands south of the border.

I quickly discovered that my sudden change of heart was gathering a flow of Facebook “likes”, including from English friends aghast at the result of the vote.

“Can I become Scottish?” commented one, with more than a hint of desperation. “Surely as I have a UK passport I can choose which bit I belong to?”

Of course, your Facebook account serves as an echo chamber, but at some moments it is also a comfort zone where you can share your feelings instantly with like-minded friends. And as it turned out, the feeling that most of my friends were sharing was that they felt almost physically sick at the result.

(AFP / Oli Scarff)

(AFP / Oli Scarff)Joining the pro-independence camp has certainly taken me a very long time.

I was born in what I would call the old coal-smoke Glasgow of the 1950s. It was a predominantly working class city of grey tenements, where cloth-capped men worked in the shipyards like their fathers before them; of football matches at Hampden Park stadium from which the roar of 120,000 fans – the “Hampden roar” – could be heard across the city; of the annual Glasgow Fair holiday when parents scooped up suitcases and kids and crammed them excitedly onto steam trains for two weeks at the seaside.

It was also a city cursed with the sectarian divide between Protestants and Catholics, which instilled a hatred of tribalism in me that has lasted until this day. The city’s football clubs Rangers and Celtic, Protestant and Catholic strongholds respectively, were temples to the bigotry that divided society in the West of Scotland.

My mother’s side of the family was Irish Catholic – my great uncle was a member of the “old” IRA in Cork fighting for independence from the British – and my father’s side Scottish Protestant. Thanks to my grandmother I have Irish citizenship, but it does not extend to the rest of the family.

A family namesake, George Wishart, was burned at the stake in St Andrews as a Protestant martyr in 1546.

The Tartan army. (AFP / Andy Buchanan)

The Tartan army. (AFP / Andy Buchanan)I went to a “non-denominational” school, which was essentially for Protestants, and I wore a blue blazer. Roman Catholics went to their own schools and wore green blazers. A sense of wariness or downright hostility towards “the other” was institutionalised and instilled in us from the youngest age.

My days as a young reporter in Scotland in the 1970s coincided with the first golden period for the Scottish National Party as the discovery of oil in the North Sea led to an upsurge in support for independence and “It’s Scotland’s oil” was used as an SNP slogan.

What will happen when it runs out, I thought, and I never took the independence movement that seriously.

Pro EU campaigners demostrate outside the Scottish Parliament in Edinburgh, Scotland on June 28, 2016 (AFP / Andy Buchanan)

Pro EU campaigners demostrate outside the Scottish Parliament in Edinburgh, Scotland on June 28, 2016 (AFP / Andy Buchanan)At the same time, I had begun travelling -- first to France and then the length and breadth of Europe on an Interrail pass. This experience was the beginning of a lifetime fascination with discovering and experiencing other cultures.

Or at least that has been the case until the door apparently slammed shut on the morning of June 24, 2016, when the Brexit result was announced.

My worries are shared by many expat Britons in Europe now. And like me, many parents have seen their children deprived, from one day to the next, of their European birthright.

So hence my case for Scottish independence.

I’m not what I would call a “tartan” expat. In my years away from Scotland I have gone to the occasional Burns supper but have never joined St Andrew’s societies or worn a kilt (in fact I’ve never worn a kilt in my life).

Wearing his heart on his kilt.

(AFP / Lesley Martin)

Wearing his heart on his kilt.

(AFP / Lesley Martin)At the same time, the sense of national identity never leaves you.

I interviewed Scottish First Minister Alex Salmond with an AFP colleague in Hong Kong in 2013, when the independence referendum was in its early planning stages. He was gregarious and engaging and remembered my father – also called Eric Wishart - who had been the night editor of the Glasgow Herald when Salmond was starting his political career. But I was unconvinced by his arguments for independence, and I felt that, deep down, he did not expect Scotland to vote in favour.

When it finally came to the referendum itself, I found that I was disenfranchised along with many fellow Scots who had lived abroad for too many years to be eligible to vote. I was firmly against independence for clear reasons – apart from the economic uncertainty and my dislike of nationalism, we had the best of both worlds as far as I could see. Scotland was already a country (although many people find the concept of Scotland being a country within a country difficult to grasp) with a strong national identity – the home of golf, the whisky industry, great seats of learning in Glasgow and Edinburgh. We had our own parliament and first minister, with tax raising powers and control over education, justice, health, agriculture and other sectors. We had our own Scottish pound, church, legal and education systems, our own national sports teams and our own language (Gaelic) too -- if anybody could be bothered to learn it.

The author (r) with Alex Salmond, a former first minister of Scotland who oversaw the independence referendum in 2014. (AFP)

The author (r) with Alex Salmond, a former first minister of Scotland who oversaw the independence referendum in 2014. (AFP)And at the same time, as part of the United Kingdom we punched above our weight internationally as key members of NATO, the United Nations and, of course, the European Union. The arguments in favour of independence seemed more emotional than anything else – invoking the spirit of Scottish heroes William Wallace and Robert the Bruce: “We’ll rise to be a nation again,” “We’re fed up with being ruled by Westminster”, “We have to shrug off the English yoke”, etc., etc. There was no convincing rationale for independence that I could see.

But now that the UK has voted to leave the EU, there are plenty of reasons for Scotland to break away.

Scotland had voted overwhelmingly to remain part of the European Union and England had voted to leave. To quote the comedian Billy Connolly: ”Scotland gets fed up – no matter what they vote for they get what England votes for”.1

As far as I could see, much of the Leave campaign had exploited people’s frustrations and fears and played to the kind of tribalism I grew up with in Glasgow: the hatred and fear of the other, of the alien hordes taking our jobs and threatening our very way of life. And, there was the political expediency that underpinned the whole exercise.

The mood in Edinburgh after the Brexit vote.

(AFP / Oli Scarff)

The mood in Edinburgh after the Brexit vote.

(AFP / Oli Scarff)I feel desperately sorry for the generations of young people who may never enjoy the same freedom to travel, study, work and settle in Europe as the British have been able to do for the past 40 years.

And hence my conversion to the independence cause. It seemed unjust that Scotland and its people, against their will, should become part of Fortress Britain under the sway of Westminster and, dare I say it, the strident nationalism of Little England -- deprived of the benefits of membership of the EU, whatever its flaws.

(AFP / Odd Andersen)

(AFP / Odd Andersen)If the only path forward for Scotland and its people, if they want to remain part of Europe, is to break away from the United Kingdom and apply for EU membership, with all the ramifications and uncertainties that this will entail, then so be it.

Only hours after my Facebook post the Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon announced that the Brexit vote represented a “material change” since the Scottish independence referendum and that as a result a second vote on independence was “highly likely”.

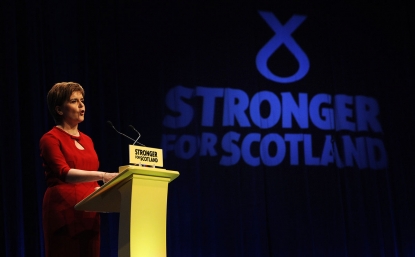

Nicola Sturgeon at the SNP Conference in Aberdeen, on October 17, 2015 (AFP / Andy Buchanan)

Nicola Sturgeon at the SNP Conference in Aberdeen, on October 17, 2015 (AFP / Andy Buchanan)I saw her at a breakfast last year at the Hong Kong Foreign Correspondents’ Club and was impressed: she was incisive, convincing -- a modern leader for a modern Scotland.

And if she gives me a vote next time around, despite all the attendant economic and other uncertainties, it would be in favour of an independent Scotland as a member, hopefully, of a united Europe.

(AFP / Oli Scarff)

(AFP / Oli Scarff)