One blog by Michèle: Covering the 'Islamic State'

It was with immense sadness that the Agency’s journalists learned on Tuesday May 4 of the death of Michèle Léridon, 62, AFP’s Global News Director between 2014 and 2019. During her 37-year career at AFP, she left her mark on the newsroom through her warmth, her intellect and the considerable legacy she left through reforming the Agency, as well as her battle on behalf of women and against misinformation. At the Agency’s daily news conference, current Global News Direction Phil Chetwynd emphasised the “force” that characterised her and her “clarity” when it came to ethical issues in the digital era. She draw up the AFP Charter and our sourcing guidelines that remain the Agency’s benchmark today.

We are today republishing this blog originally written in 2014 that perfectly reflects the finesse with which she tackled ethical questions. The piece was written at a time when journalists were increasingly being captured and killed and when Islamic State propaganda – each worse than the last – was being widely disseminated, leading AFP to change our working methods and guidelines.

PARIS, September 17, 2014 – Faced with the kidnap and murder of journalists in Syria, Iraq and Africa, and the flood of horrific propaganda images churned out by the "Islamic State" group and its offshoots, it is time to reaffirm some ethical and editorial groundrules.

Our challenge is to strike a balance between our duty to inform the public, the need to keep our reporters safe, our concern for the dignity of victims being paraded by extremists, and the need to avoid being used as a vehicle for hateful, ultraviolent propaganda.

This is what the events of recent months have changed in the work environment of a global news agency such as AFP, and how we have responded.

Covering the conflict from a distance

The frontline seen through a telescopic rifle belonging to a Kurdish Peshmerga sniper in the Gwer district, northern Iraq, on September 15, 2014 (AFP Photo / JM Lopez)

The frontline seen through a telescopic rifle belonging to a Kurdish Peshmerga sniper in the Gwer district, northern Iraq, on September 15, 2014 (AFP Photo / JM Lopez)In Syria we are currently the only international news agency with a bureau in Damascus, manned by a team of Syrian journalists. We still regularly send reporters from Beirut into areas controlled by forces loyal to President Bashar al-Assad. We also continue to cover the rebel side of the conflict thanks to local stringers, who live in the area and who supply us with accounts, photos and videos of what is happening there.

Since August 2013, we have stopped sending any journalists into rebel-held parts of Syria. The situation there is out of control, and far too dangerous. A foreign reporter venturing into those lawless areas runs a serious risk of being kidnapped or killed, as tragically happened to James Foley, a regular AFP contributor murdered by IS militants in August.

Journalists are no longer welcome in rebel-held Syria, as independent witnesses to the suffering of local populations. They have become targets, or commodities to be traded for ransom.

That is also why we no longer accept work from freelance journalists who travel to places where we ourselves would not venture. It is a strong decision, and one that may not have been made clear enough, so I will repeat it here: if someone travels to Syria and offers us images or information when they return, we will not use it. Freelancers have paid a high price in the Syrian conflict. High enough. We will not encourage people to take that kind of risk.

Fighters from the Nureddine al-Zinki unit, a moderate Syrian opposition faction affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood, take position near Aleppo on Septembrer 11, 2014 (AFP Photo / Baraa al-Halabi)

Fighters from the Nureddine al-Zinki unit, a moderate Syrian opposition faction affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood, take position near Aleppo on Septembrer 11, 2014 (AFP Photo / Baraa al-Halabi)In a war zone there are always pockets of relative safety where a journalist can work, file stories, and get some rest. What makes Syria different is the lack of any such safe haven in the rebel-held zone. The country is dangerous from one end to the other.

We do however still send a great many reporters -- and employ freelancers -- to cover Iraq and other war zones from Ukraine to Gaza or the Central African Republic.

A news agency cannot stop covering conflict. But we do everything we can to keep our teams safe. Firstly by sending journalists who are trained to operate in hostile environments. Secondly, by equipping them with full protective gear from helmets to flak-jackets. We also hold a detailed briefing with reporters before and after every such mission. Sharing information with other media is vital. When journalists' safety is at stake, competition no longer applies.

A flood of horrors

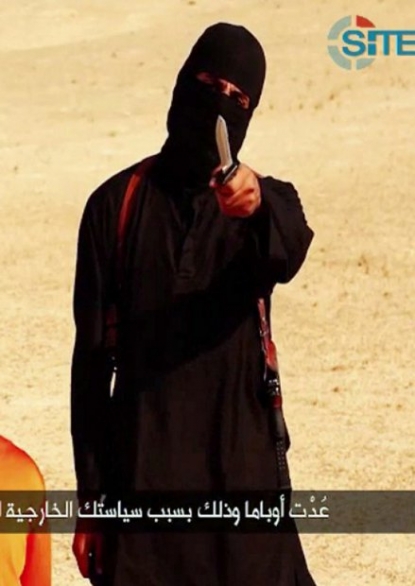

An image grab taken from a video released by IS jihadists on September 2, 2014 shows a masked militant speaking to the camera before beheading US reporter Steven Sotloff (AFP Photo / HO / Site Intelligence Group)

An image grab taken from a video released by IS jihadists on September 2, 2014 shows a masked militant speaking to the camera before beheading US reporter Steven Sotloff (AFP Photo / HO / Site Intelligence Group)The Islamic State group is confronting us with an unprecedented use of images intended to terrorise. Working in IS-controlled areas is virtually impossible for journalists and independent observers. That means that propaganda photos and videos released by IS are often our only sources of information about what is happening inside the self-declared "caliphate".

These images are often atrocious, inhuman, featuring beheadings, crucifixions and mass killings. They are extremely painful to receive, and to watch. In Nicosia, our hub for the Middle East and North Africa, and Beirut which heads up our Syria coverage, the journalists whose job it is to examine such footage have been deeply affected.

But IS images do provide information, especially when hostages are involved. Videos can provide proof of life, or death. We cannot look the other way, or avoid reporting on them. This raises a number of editorial and ethical questions.

Our first instinct, when we receive a video of a hostage being beheaded, would be not to move it to our clients to avoid spreading IS's bloody propaganda. But from the moment the images contain information, as a news agency we have a duty to use them.

IS militants wave a flag above the heads of prisoners who are about to be executed. (AFP / HO / Welayat Salahuddin)

IS militants wave a flag above the heads of prisoners who are about to be executed. (AFP / HO / Welayat Salahuddin)To do so we must tread carefully. First, we identify the source of the footage and explain the context in which we received it. Secondly, we do not broadcast staged scenes of violence. That is why AFP did not provide its clients with any of the recent videos showing hostages being beheaded.

We released only a very small number of still images from those videos, and tried to ensure they were the least degrading towards the victims. Each time we showed a close-up of the victim's face, the executioner's face, and that of the person designated as the next victim. In the case of the slain British aid worker David Haines, it was a challenge to find a still that was not degrading given that the hostage's killer had his hand placed permanently on his neck.

We also try to seek out and publish photos of the victim taken before their ordeal, to try to give them back some dignity in death.

These are tough questions facing all news media. On September 11 this year we invited leading French print and broadcast media to debate the subject with AFP's senior editors and the media historian Patrick Eveno. We have also raised it with our international counterparts at the BBC, Reuters and AP.

Some have chosen not to broadcast any such footage, while acknowledging that to ignore it is problematic too -- since it amounts to covering up a violent reality.

British aid worker Alan Henning, currently held by IS militants and threatened with execution, in a refugee camp on the Turkish-Syrian border at an undisclosed date (AFP Photo / Foreign and Commonwealth Office)

British aid worker Alan Henning, currently held by IS militants and threatened with execution, in a refugee camp on the Turkish-Syrian border at an undisclosed date (AFP Photo / Foreign and Commonwealth Office)"Let no one say they did not know" about IS atrocities, is the argument most often cited to justify publishing the grisly propaganda.

Other media have chosen to show beheading videos in full, including footage of hostages lashing out at US President Barack Obama for his Middle East policies. AFP refuses to broadcast statements made under duress by a person who is about to die.

There is no perfect answer. We have chosen to be as sober as possible, to take as much distance as we can, and to take every care not to be taken in by trick footage.

We decide whether to publish each video on a case by case basis, after weighing up the value of the information it contains and its context.

IS videos are widely available online. Media can equally invoke that fact to justify a decision to publish, or not to publish. We at AFP feel that our job is to sort through and select from the images. That is journalism. If we broadcast something simply because it is available everywhere, we are offering no added value.

On the other hand, the fact that IS videos are widely accessible relieves us of having to decide whether to provide them to our clients: anyone who absolutely wants to use a clip in full can find it readily, without AFP's help.

What to call IS militants?

An image made available by Jihadist media outlet Welayat Raqa on June 30, 2014, allegedly shows an IS militant parading in the northern rebel-held Syrian city of Raqa (AFP Photo / HO / Welayat Raqa)

An image made available by Jihadist media outlet Welayat Raqa on June 30, 2014, allegedly shows an IS militant parading in the northern rebel-held Syrian city of Raqa (AFP Photo / HO / Welayat Raqa)We have decided no longer to use the expression "Islamic State" as the jihadist movement rebranded itself a few months ago. From now on AFP will refer to it as "the Islamic State group" or "Islamic State organisation", and as "IS jihadists" in headlines and news alerts.

The Arabic acronym for the group's full original name, Daesh, while used by some governments including France, is hard for most readers to relate to.

An international news agency cannot be pressured into using subjective terms like "terrorists" or "slayers". Nor can we alter the name an organisation has chosen for itself.

But we feel giving its name simply as "Islamic State" is inappropriate for two reasons. Firstly this is not a state, with borders and international recognition. Secondly, a great many Muslims consider the values driving this organisation to have nothing to do with Islam. The name "Islamic State" is therefore doubly likely to mislead the public.

Michèle Léridon was AFP's Global News Director from 2014 to 2019.