Will journalism recover from Covid-19?

Paris - Insidiously, the coronavirus is attacking journalism’s vital functions. Since the beginning of 2020, journalists’ daily work has been transformed as countless events have been cancelled or access to them has been limited or curtailed and press conferences have turned virtual. Though understandable on health grounds, the restrictions have turned the practising of our profession upside-down.

A feeling has crept in among journalists that these restrictions are sometimes being applied excessively and used as a pretext to keep the media at a distance. Today, as we mark World Press Freedom Day, we face this worrying question: Will we ever regain the full level of access to cover events that we had before the pandemic? Will freedom and plurality of information also fall victim to Covid-19 - and at a time when, amid a wave of coronavirus-related misinformation, there has never been such a vital need for quality journalism?

In this picture taken on March 31, 2020 a municipal worker sprays disinfectant solution on AFP photographer Lakruwan Wanniarachchi in Colombo

(AFP)

In this picture taken on March 31, 2020 a municipal worker sprays disinfectant solution on AFP photographer Lakruwan Wanniarachchi in Colombo

(AFP)Masking up

Despite the health crisis, AFP journalists, like many others, have continued to do their job by reporting what is happening on the ground. They have had to overcome their own anxiety while facing scenes of ordinary people in despair and sometimes of hostile demonstrators without masks. They have done so voluntarily and in spite of the fear of infection for themselves or their loved ones.

Health workers attend patients inside a banquet hall temporarily converted into a covid care centre in New Delhi on April 28, 2021 (AFP / Prakash Singh)

Health workers attend patients inside a banquet hall temporarily converted into a covid care centre in New Delhi on April 28, 2021 (AFP / Prakash Singh) Mass cremation at a crematorium in New Delhi on April 27, 2021 (AFP / Prakash Singh)

Mass cremation at a crematorium in New Delhi on April 27, 2021 (AFP / Prakash Singh)Over the past year we have been unbending in our commitment to get out in the field to investigate, to report first-hand, to show and explain what is hidden from view: an invisible virus; events under lockdown; a pandemic so vast that it is difficult to comprehend. Masks, goggles, sometimes full-body overalls have become a reporter's working outfit.

But other constraints have also become the norm. Events are held behind closed doors, in a sanitary bubble. Press conferences are held remotely via the internet and have become ever more stage-managed. These are just two of the kinds of media restrictions, widely experienced by AFP journalists, that have curbed the functioning of the media during the pandemic.

G20 leaders attend a virtual summit on March 26, 2020 (AFP / Gary Ramage)

G20 leaders attend a virtual summit on March 26, 2020 (AFP / Gary Ramage)Over the past year we have lost count of the events that have been closed to the media and summed up afterwards by a mere emailed statement with photographs and videos provided by the organisers - known in journalistic jargon as “handouts”. No questions, no face-time with those involved; just a tightly-calibrated statement that leaves you with the feeling you are not being told the whole story.

In Germany “some political events have turned into show-marketing,” says AFP’s Berlin bureau chief Yacine Le Forestier. “Neverending self-promotion films with no questions from the audience or the press.”

When French ministers travelled to Algeria in late 2020, AFP had no access to cover the visit. Because of Covid, we were told, there would be an official statement and no images. Move on! Nothing to see here.

Sports events have resumed but coverage conditions have tightened (AFP / Franck Fife)

Sports events have resumed but coverage conditions have tightened (AFP / Franck Fife)New rules

Sports events are staggering back to life after a shutdown lasting months. But sports coverage has not been spared from the damage. AFP habitually films press conferences and training sessions around big games, if not the sports action itself for rights reasons. But in the post-Covid world, even this access has diminished.

“We no longer have video access to nearly all the big sporting events: the European Championships, the Olympic Games, football leagues in Europe, the Champions League, the Six Nations rugby,” says Guillaume Rollin, AFP’s sports-video chief editor.

“Paris Saint Germain has ended all press activity at its training centre,” says our football reporter Emmanuel Barranguet. “Everything takes place virtually via Zoom.”

“In football, Covid-19 has done away, possibly for good, with a space that was the spice of sports coverage: the mixed zone,” says Jean Decotte, AFP’s world football coordinator. “That was where footballers could speak freely to the microphones without a communications team filtering it.”

Real Madrid's French coach Zinedine Zidane and Real Madrid's Portuguese forward Cristiano Ronaldo celebrate winning the Liga title after the Spanish league football match Malaga CF vs Real Madrid CF at La Rosaleda stadium in Malaga on May 21, 2017. (AFP / Jose Jordan)

Real Madrid's French coach Zinedine Zidane and Real Madrid's Portuguese forward Cristiano Ronaldo celebrate winning the Liga title after the Spanish league football match Malaga CF vs Real Madrid CF at La Rosaleda stadium in Malaga on May 21, 2017. (AFP / Jose Jordan)Divide and pool

Before Covid, pools were already a common means of managing mass coverage of scheduled events. A small group of journalists - often a single reporter each for text, photo and video -- attend the event and share their coverage with all the other accredited media. This has long been the system in place for enabling the large White House press corps to cover a US president’s public activities.

Pool coverage ends up being identical in all media since it depends on the output of just one journalist in each format, without the richness that comes of having an event covered from various viewpoints. “In the pandemic, we have seen pools become widespread, to the point that they are becoming standard practice,” says AFP’s global photo chief editor, Stephane Arnaud.

For TV images, says our video chief editor, Mehdi Lebouachera, “access for covering public declarations has become very problematic,” with many instances where only one camera is allowed. “At best, the content is the same for all media organisations. At worst, preference is given to selected ones.”

Places in press briefings have been reduced and pool systems have become common (AFP / Jim Watson)

Places in press briefings have been reduced and pool systems have become common (AFP / Jim Watson)In the United States, this impact from health restrictions was felt most strongly by our teams seeking access to Joe Biden during his presidential campaign. “All the events were covered by a pool, including the campaign rallies, which in any case were always small-scale,” says AFP’s North America chief editor Herve Rouach.

Access to Congress and the White House has been likewise restricted. “In the press room of the West Wing, the number of places has been reduced in order to keep a distance between the journalists,” who must take turns to attend briefings in person, he says.

Feeding a line

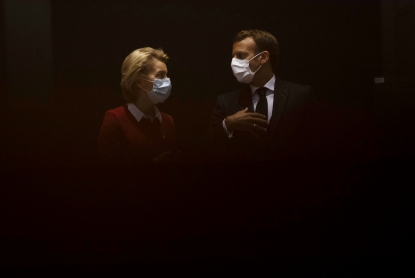

In Brussels, pool-law reigns at the top EU institutions, the European Council and European Commission. “We no longer get the chance to take photographs of Ursula von der Leyen, except for her rare appearances in the press room,” says our photographer Kenzo Tribouillard, referring to the head of the commission. “Meanwhile the leaders’ official television channels and social media are full of events that we have no access to,” such as when Von der Leyen received her Covid vaccination.

After we passed 100 million vaccinations in the EU, I’m very glad I got my first shot of #COVID19 vaccine today.

— Ursula von der Leyen (@vonderleyen) April 15, 2021

Vaccinations will further gather pace, as deliveries are accelerating in the EU.

The swifter we vaccinate, the sooner we can control the pandemic. #StrongerTogether pic.twitter.com/ZmbjlmFOn4

In video, conditions are no better. “Often we have no choice but to take the institutional video feed, since there is no possible access to the events,” says video reporter Kilian Fichou. Before the pandemic, dozens of journalists got the chance to put questions to European heads of state at summits. “Now they just speak to one camera on arriving, surrounded by a rather unreal silence.”

It is hard to see where respect for health measures ends and a desire to limit media access begins. But, says Killian, “we have the impression that a lot of doors have closed, and it will be very difficult to open them again.”

President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen talks with France's President Emmanuel Macron prior to the start of the EU summit in Brussels, on July 18, 2020 (AFP / Francisco Seco) (AFP / Francisco Seco)

President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen talks with France's President Emmanuel Macron prior to the start of the EU summit in Brussels, on July 18, 2020 (AFP / Francisco Seco) (AFP / Francisco Seco)In Germany, restrictions were so disruptive to coverage that journalists waited in line overnight outside a courthouse on foam mattresses and camping chairs to be sure of getting a place to cover a trial, Reporters Without Borders said in a report. “It is a shame that pools are now used systematically in places that were previously open to all, or nearly - even though it is hard to argue with the health reasons,” says Annie Thomas, AFP chief editor for France.

For journalists covering the French government, a pool system has long been in place at France’s Elysee presidential palace, but its use has been extended during the pandemic. Pool-rules are being imposed for more and more ministerial activities - even events out in public, although some media “gaggles” are still occasionally authorised: free-for-alls with microphones, dictaphones and notebooks deployed at will.

Coverage of glamour events has also been undermined. No AFP photographer or video journalist was allowed in to this year’s Oscar ceremony. Output came from a pool and in the form of handouts from organisers.

Peter Spears, Frances McDormand, Chloe Zhao, Mollye Asher et Dan Janvey winners of the award for best picture for Nomadland, pose in the press room at the Oscars on April 25, 2021 (AFP / POOL/ Chris Pizzello)

Peter Spears, Frances McDormand, Chloe Zhao, Mollye Asher et Dan Janvey winners of the award for best picture for Nomadland, pose in the press room at the Oscars on April 25, 2021 (AFP / POOL/ Chris Pizzello)Making it pay

Pools are also the norm for photographing key sports events, including football matches of the English Premier League or the French national team, the Champions League and the upcoming Euro 2020 international tournament. Photographers’ access to cricket matches during England’s recent tour of India was restricted, even though the games in question were open to text reporters and spectators.

Journalists fear organisers aim to profit by controlling photo rights to sports events (AFP / Sajjad Hussain)

Journalists fear organisers aim to profit by controlling photo rights to sports events (AFP / Sajjad Hussain)“Some journalists on the ground feel that Covid has given the Indian board the perfect excuse to restrict outside photo coverage and replace it with hand-outs, giving it the opportunity to control production and benefit commercially from the exclusive pictures,” says our Asia-Pacific sports coordinator, Talek Harris.

A news agency like AFP pays its journalists for their news-gathering work and its associated technical costs. The agency’s charter forbids them from paying their sources.

“In the sports world, there are enormous financial stakes depending on images. In television, only the holders of access rights can film and broadcast the sporting action. The fear is that this model could now start to apply to photographs, with organisers aiming to make money from the distribution and resale of photos,” says Stephane Arnaud. “The future is looking tough.”

Bottled at source

Maintaining a variety of sources is an essential task for journalists so that their reporting can be as broad-based as possible. Acquiring new sources as the news evolves involves formal encounters but also spontaneous and informal ones. That has become complicated in a time of physical distancing and video conferences.

When journalists lack direct access to alternative sources, “how can they provide the necessary counterbalance to official statements bursting with well-meaning platitudes and nondescript speeches?” says our world economics editor Aurelia End, a regular attendee at G20 summits and the World Economic Forum.

Former US President Donald Trump waves upon his arrival at the Economic Forum (WEF) annual meeting on January 25, 2018 in Davos, eastern Switzerland (AFP / Fabrice Coffrini)

Former US President Donald Trump waves upon his arrival at the Economic Forum (WEF) annual meeting on January 25, 2018 in Davos, eastern Switzerland (AFP / Fabrice Coffrini)“Video conferences literally screen out everything but carefully prepared messages, The microphone only picks up the words. Journalists often have to submit their questions in advance and they rarely get a chance to ask follow-up questions.”

Press conferences on Zoom end with no questions, or questions only from local media, then the words “Sorry, we’ve run out of time,” complains one of our reporters in the Gulf. “Zero opportunity for follow-up even if we can ask something. The Zoom interface is a godsend for their hyper-control of these events.”

Russian President Vladimir Putin attends the G20 summit hosted by Saudi Arabia via video conference at the Novo-Ogaryovo state residence, outside Moscow, Russia, on November 21, 2020. (AFP / Alexey Nikolsky)

Russian President Vladimir Putin attends the G20 summit hosted by Saudi Arabia via video conference at the Novo-Ogaryovo state residence, outside Moscow, Russia, on November 21, 2020. (AFP / Alexey Nikolsky)

Video conferences may have one advantage: they can make an event accessible to a far greater number of people than the average briefing room. Formula One teams have understood this: they have let reporters put questions to their drivers online at Grand Prix races where in-person access was limited. Media that are not able to travel to every Grand Prix were grateful for this increased access for interviews, says AFP motorsports correspondent Raphaelle Peltier.

On the other hand, she notes, such interviews are of inferior quality since it is hard to bounce back with follow-up questions through a computer screen and mic. And only by being at the race track itself can you get priceless coverage such as Raphaelle’s detailed account, at the 2020 Bahrain Grand Prix, of driver Romain Grosjean’s spectacular escape from a fiery wreck.

AFP's reporter was at the track covering the Bahrain Grand Prix when Romain Grosjean crashed (AFP / Kamran Jebreili)

AFP's reporter was at the track covering the Bahrain Grand Prix when Romain Grosjean crashed (AFP / Kamran Jebreili)Misinformation super-highway

With less margin for on-the-ground journalism and given the scope for mass communication provided by social media, a misinformation super-highway has opened up.

In a major survey by the International Centre for Journalists early in the pandemic, more than 80 percent of journalists questioned said they had encountered false news at least once a week. Of these, 46 percent pointed to political leaders as the source.

A woman with a QAnon shirt stands with hundreds of people to protest a mandate from the Massachusetts governor requiring children to receive a flu vaccine to attend school in Boston, in August 2020 (AFP / Joseph Prezioso)

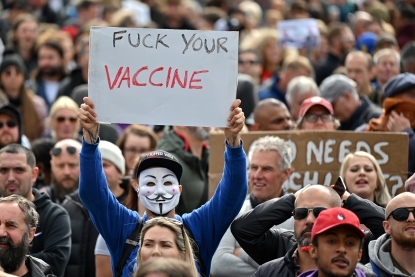

A woman with a QAnon shirt stands with hundreds of people to protest a mandate from the Massachusetts governor requiring children to receive a flu vaccine to attend school in Boston, in August 2020 (AFP / Joseph Prezioso)“The coronavirus pandemic has provided fertile ground for conspiracy theorists and anti-vaccine campaigners to spread confusion and amplify their messages, playing on public fears about health risks and constantly evolving health policies,” says Sophie Nicholson, deputy chief editor in AFP’s digital investigation team.

“We’ve seen similar misinformation spreading across the globe as the pandemic has played out, from false cures to rejections of masks or unproven claims about harmful effects of vaccinations,” says Sophie Nicholson. “These posts can be shared in good faith by members of the public and are often boosted with support from celebrities or politicians.”

People protest against Covid-19 vaccines and restrictions in the front of the Romanian government headquarters in Bucharest on April 10, 2021 (AFP / Daniel Mihailescu)

People protest against Covid-19 vaccines and restrictions in the front of the Romanian government headquarters in Bucharest on April 10, 2021 (AFP / Daniel Mihailescu)With our unique network of more than 100 specialised journalists dedicated to this task, AFP has published nearly 3,300 fact-check articles in 18 languages since January 2020. They have played a vital role at a time when bogus recommendations have spread online, such as those telling people to use toxic disinfectant as a treatment for Covid, as Donald Trump himself had suggested while he was US president.

Room for debate

What has become of our newsrooms themselves, those vibrant crucibles of ideas, debate, critical enquiry and creativity? Distance-working has deprived us of these exchanges; the lack of them has made us appreciate their richness and vitality.

During the various coronavirus restrictions, journalists have found themselves isolated behind their computer screens, connecting with one another via typed messages and on-screen editorial conferences.

AFP journalists at work during the presidential election night at the AFP office in Washington DC on November 3, 2020 (AFP / Eric Baradat)

AFP journalists at work during the presidential election night at the AFP office in Washington DC on November 3, 2020 (AFP / Eric Baradat)Those on the front line reporting on the death and despair day after day have seen their usual psychological defences crumble. Among the journalists surveyed at the start of the pandemic, the biggest complaint was the psychological and emotional impact of the crisis. That was followed by unemployment or financial worries (67 percent) and the heavy workload (64 percent), according to the ICFJ.

Faced with the risk of stress, depression and burnout, AFP opened access to a psychological support platform for its staff around the world. But what of the thousands of other news organisations, freelancers and stringers financially weakened by the pandemic?

Turning the page?

“The coronavirus pandemic has been used as grounds to block journalists’ access to information sources and reporting in the field,” said Reporters Without Borders in a recent report. “Will this access be restored when the pandemic is over?” The NGO’s data indicate that journalistic activity is totally or partially blocked in more than 130 countries, said its secretary general, Christophe Deloire.

With restricted access to information and press freedom and plurality under threat, the current crisis provides all the ingredients for lasting damage to journalism.

“The Davos forum and G20 summits will certainly resume in-person,” says Aurelia End. “But will the press be invited, even at a distance, even under watchful guard in a remote press centre? Or will they be left behind their screens, further away than ever from the reality of the power games?”

Once the tragedy of Covid is over, the battle will begin - stubbornly and without illusions - to win back the lost ground of press freedom. Fact-checking operations may fight against the most viral fake news once the can of worms has been opened, but on-the-ground journalism remains the best defence against misinformation.

(AFP / Justin Tallis)

(AFP / Justin Tallis)This battle must be fought by all journalists, in all media - but also by governments, decision-makers, indeed by all citizens committed to one of the crucial pillars of democracy.

We know very well that none of us will emerge unscathed from this worldwide trauma. But you can bet that soon, like the weeds in your garden, journalism will grow back through the cracks in society’s freedoms.

Supporters and employees of ABS-CBN protest in Manila on February 21, 2020 (AFP / Basilio Sepe)

Supporters and employees of ABS-CBN protest in Manila on February 21, 2020 (AFP / Basilio Sepe)Text written by Global editor-in-chief Sophie Huet with contributions from our newsroom. Translated by Roland Lloyd Parry