Battle in paradise

Cali (Colombia) - I am from Cucuta in northeastern Colombia but I have lived for more than 13 years in Cali, the country’s third-biggest city. I love this place. It has a pleasant warm climate, about 28 degrees Celsius on average. The people are friendly and the countryside is spectacular and very diverse.

Two and a half hours’ drive away is Buenaventura, on the Pacific coast. The sea there is rough, very different from the Caribbean, but captivating all the same. Not far away there are tropical forests and beaches. There are amazing hump-backed whales and thousands of birds that my daughter Martina adores.

The Cauca region around Cali has spectacular wildlife (AFP / Luis Robayo)

The Cauca region around Cali has spectacular wildlife (AFP / Luis Robayo) Humpback whales can be seen off Colombia's Pacific coast a few hours from Cali (Miguel Medina)

Humpback whales can be seen off Colombia's Pacific coast a few hours from Cali (Miguel Medina)

Cali is the capital of the Valle del Cauca department. It has broad plains but also mountains. It is where part of the Andes range begins. This city I love should be a paradise. But in the recent weeks of unrest, it has been turned into a battlefield.

Cauca has traditionally had a busy rural economy (AFP / Luis Robayo)

Cauca has traditionally had a busy rural economy (AFP / Luis Robayo)

Having the port of Buenaventura nearby makes this a busy place. There are big sugar factories. The population is diverse, with Afro-Caribbean and indigenous people as well as those who have moved here from other countries. The cultural diversity is incredible. You can have an enjoyable life in Cali.

Revellers dance in Cali's "Salsadrome" on Christmas Day 2017 (AFP / Luis ROBAYO)

Revellers dance in Cali's "Salsadrome" on Christmas Day 2017 (AFP / Luis ROBAYO)The people here love to have fun and party. It is the capital of salsa music and dancing. But Cali also suffers.

There is poverty, unemployment, racism and, yes, drug-trafficking. Buenaventura is the port from which a lot of drugs are shipped to Central America and the United States. There is much mistrust of the authorities. In these ways, Cali seems to have come to embody all of Colombia’s ills.

The Colombian navy captures a drug-trafficking submarine in Buenaventura in March 2021 (AFP / Luis Robayo)

The Colombian navy captures a drug-trafficking submarine in Buenaventura in March 2021 (AFP / Luis Robayo)Among the most recent, it has been the heart of the unrest that exploded on April 28 with mass protests against the government’s tax plans - in a context worsened by the coronavirus pandemic. NGOs say that scores of people have been killed in the violence - dozens of them in Cali.

This region’s troubles run deep. A peace deal was signed with the FARC rebels in 2016, but new armed groups have emerged, determined to take control of the territory ceded by the former guerrilla group.

A Colombian marine on patrol in Buenaventura in February, 2021 (AFP / Luis Robayo)

A Colombian marine on patrol in Buenaventura in February, 2021 (AFP / Luis Robayo)Violence has broken out here again between various forces. There are dissident remnants of the FARC who rejected the peace deal. There is the ELN, Colombia’s last surviving rebel guerrilla force. There are paramilitary groups.

These bands fight between them for drug turf and control of extorsion rackets and illegal mining - and many of them make Cali the scene of their score-settling.

Drug gangs guard the streets of Cali's Siloe neighbourhood (AFP / Luis Robayo)

Drug gangs guard the streets of Cali's Siloe neighbourhood (AFP / Luis Robayo)The security situation has deteriorated. It is has become very dangerous to travel to Cauca. At the same time, thousands of people fleeing the conflict are moving into the city.

Unemployment is at nearly 19 percent. People scrape around for whatever work they can find. With no backing from the government, banks are making little effort to help people who are struggling to pay off their loans and risk having their property seized.

All this is causing a lot of crime. You might be sitting in a restaurant and all at once armed men will pull up on a motorbike. In a few seconds they have taken the customers’ telephones, jewellery and money and off they go. There is a lot of fear. When people hear a motorbike approaching, they get frightened.

(AFP / Luis Robayo)

(AFP / Luis Robayo) Like many cities around the world, Cali has been under curfew in the pandemic (AFP / Luis Robayo)

Like many cities around the world, Cali has been under curfew in the pandemic (AFP / Luis Robayo)There are several strands to the protest movement in Cali and other cities in Colombia - labour unions, students, indigenous groups - and their demands are various.

It is not just youngsters at the demonstrations - older men and women are joining in too and some of the demonstrators are quite elderly. People are calling for social equality and are angry because they are suffering from fuel shortages.

Protests in Cali, May 10, 2021 (AFP / Luis ROBAYO)

Protests in Cali, May 10, 2021 (AFP / Luis ROBAYO)It reminds me of the demonstrations I covered a few years ago in Venezuela. Just like there, I now found the streets of my own city blocked and barricaded.

A demonstrator is hit by a Molotov cocktail thrown during clashes with riot police officers in Cali, on May 3, 2021. (AFP / Luis Robayo)

A demonstrator is hit by a Molotov cocktail thrown during clashes with riot police officers in Cali, on May 3, 2021. (AFP / Luis Robayo)

The night of May 3 was one the worst I have seen since the protests started. I could hear helicopters circling overhead, explosions, gunshots, ambulance sirens. I was still hearing them at two or three o’clock in the morning.

The disturbances started in Siloe, a district about ten blocks from my home. It has always been a violent neighbourhood. The soldiers and police went in. The shooting started. Some of the officers got injured and people were killed. One of them was a student protester. These were ordinary people protesting for better living conditions. They had families. It was sad.

The Siloe district, heart of some of Cali's fiercest unrest (AFP / Luis Robayo)

The Siloe district, heart of some of Cali's fiercest unrest (AFP / Luis Robayo)My AFP colleagues interviewed 12 witnesses who said riot police and special forces charged a peaceful protest.

One Friday at the end of May, before night fell, civilians wearing bullet-proof vests fired at protesters as the police watched. That day Colombia was marking one month of protests, and 13 people in the city were killed. According to authorities, eight of those had been shot.

Locals mourn young people killed in the clashes of May 3 (AFP / Luis Robayo)

Locals mourn young people killed in the clashes of May 3 (AFP / Luis Robayo)

In five weeks of unrest, 59 people have died across Colombia according to official data, with more than 2,300 civilians and uniformed personnel injured. The NGO Human Rights Watch says it has “credible reports” of at least 63 deaths nationwide.

Beyond the demonstrations, what has most upset me in recent months are the funerals of victims of the broader conflict between the armed groups.

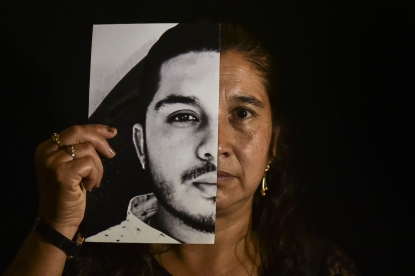

Lucila Huila, 53, poses with the photo of her son Esneider Collazos, 23, in Popayan, Cauca Department, Colombia, killed by alleged members of an armed group (AFP / Luis Robayo)

Lucila Huila, 53, poses with the photo of her son Esneider Collazos, 23, in Popayan, Cauca Department, Colombia, killed by alleged members of an armed group (AFP / Luis Robayo) Gladys Betancourth, 51, poses with a picture of her son Oscar Obando, killed by armed men at 24 as he was partying with friends (AFP / Luis Robayo)

Gladys Betancourth, 51, poses with a picture of her son Oscar Obando, killed by armed men at 24 as he was partying with friends (AFP / Luis Robayo)

Funerals such as that of Cristina, an indigenous leader. She and several companions were on guard at a checkpoint on the highway to Tacueyo when a car came that was suspected of having a kidnapped person inside. When they stopped the car, Cristina and her companions came under fire.

Then there was Karina Garcia, a candidate for mayor in the town of Suarez. She was murdered while campaigning.

It has been a very tough year because of the pandemic and the violence in this country. But I still have a passion for my job. It allows me to discover new worlds, all different kinds of people and incredible places, through happy times and sad. To tell the stories about people’s lives and show the world what is happening in my country.

Relatives mourned Karina Garcia, a mayoral candidate in Suarez, murdered while campaigning (AFP / Luis Robayo)

Relatives mourned Karina Garcia, a mayoral candidate in Suarez, murdered while campaigning (AFP / Luis Robayo)Account by Luis Robayo in Cali. Edited and translated by Roland Lloyd Parry in Paris