Feasts in land of famine

ADEN, Yemen – I am in Yemen, stuffing my face with food.

There is a trough-sized platter of traditional mandi -- a slow-cooked whole lamb on a bed of rice garnished with cashews and raisins. There is a mint-laced salad and hummus drizzled with olive oil. And there is another platter piled high with fresh fruit.

This scene has played itself out repeatedly during my six reporting trips across Yemen over the past year—in Yemeni homes, restaurants and military bases. Food is always aplenty, sometimes enough to feed a battalion.

A Yemeni feast is served up at a Sanaa restaurant, October, 2014.

(AFP / Mohammed Huwais)

A Yemeni feast is served up at a Sanaa restaurant, October, 2014.

(AFP / Mohammed Huwais)And so is hunger.

Twelve-year-old Fatima Hadi, who suffers from acute malnutrition, at a hospital in Yemen's northwestern Hajjah province, February, 2019.

(AFP / Essa Ahmed)

Twelve-year-old Fatima Hadi, who suffers from acute malnutrition, at a hospital in Yemen's northwestern Hajjah province, February, 2019.

(AFP / Essa Ahmed)Juxtapose my feast against another oft-repeated scene in Yemen that sometimes feels straight out of Dickens.

I’m in a crowded hospital, its fraying corridors filled with the cloying odour of antiseptic. I see faces weathered by tears and bodies broken by hunger. One of them, a desperate mother, is cradling a skeletal child with protruding ribs and hollow eyes. The infant is a bag of bones, barely clinging on to life, too weak to even cry. A doctor tries to draw blood, but can’t find the vein in the baby’s rail-thin arm.

The mother, also weak and gaunt, coos gently in the baby’s ear, clinging to hope despite the vacant stares. She and her husband have had to make an impossible choice at a time of war—cough up an unaffordable taxi fare to bring this child to hospital or feed their other children. It’s a choice that no parent should have to make.

Yemeni mother Nadia Nahari holds her five-year-old son Abdelrahman Manhash, who weighs five kilograms due to severe malnutrition, at a clinic in the western province of Hodeidah, November 2018.

(AFP)

Yemeni mother Nadia Nahari holds her five-year-old son Abdelrahman Manhash, who weighs five kilograms due to severe malnutrition, at a clinic in the western province of Hodeidah, November 2018.

(AFP)And after witnessing this, I find myself later that day staring at another feast laid out for me.

The sumptuous spreads would make for an appetising meal — if only I weren’t in a country on the precipice of famine. I mean no offense to my generous local hosts. I am extremely thankful for the warmth and hospitality that you wouldn’t ordinarily expect in a country in the grip of a brutal conflict, now in its fourth year.

But feasting in the midst of mass starvation feels jarring, even repugnant. I can feel my stomach knotting up.

Relentless war has given rise to a strange paradox in Yemen. In my years of reporting from a few warzones, I haven’t seen a country with so much food and so much hunger.

Yemen's traditional al-selth dish, made up of beef, rice and vegetables, served up at a restaurant in Sanaa in October, 2014.

(AFP / Mohammed Huwais)

Yemen's traditional al-selth dish, made up of beef, rice and vegetables, served up at a restaurant in Sanaa in October, 2014.

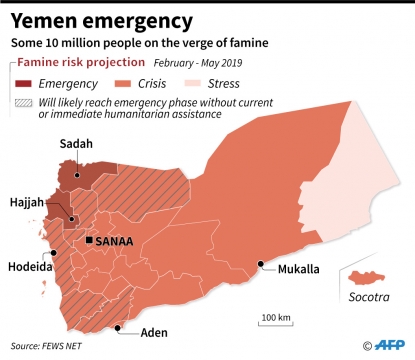

(AFP / Mohammed Huwais)The numbers reveal the scale of depravation: 15.9 million people - more than half of Yemen’s population - remain severely food insecure, especially in areas with active fighting, according to Integrated Food Security Phase Classification.

An estimated 85,000 children under five may have died from starvation or disease since the start of war, according to Save the Children.

(AFP Graphics)

(AFP Graphics)These deaths were entirely preventable.

The most striking thing about the humanitarian crisis convulsing Yemen—the world’s worst, according to the United Nations—is that it is entirely man-made.

For the warring parties in Yemen — as in other conflict zones such as Syria and South Sudan — food is a weapon of war. Starvation appears to be inflicted on people as a way to win their acquiescence. Hunger, it is believed, goads people to pick sides.

This became strikingly clear when I went on a military embed to Yemen’s Red Sea coastal city of Hodeida in late January with the Saudi and Emirati-led coalition, which is pitted against Iran-aligned Huthi rebels.

After a bloody bout of fighting, a tenuous ceasefire took hold in the western rebel-held port city after an agreement was reached between the two sides in December at UN-brokered talks in Sweden. Signed under mounting global pressure to end the war, it was hailed as a huge leap forward since the coalition entered the conflict in March 2015.

But the hard-won ceasefire is buckling under the strain of repeated skirmishes and violations reported by both sides. Aid workers warn that if the truce in Hodeida — a conduit for more than two-thirds of Yemen’s food imports and humanitarian aid — collapses, it could unleash a full-blown famine.

I travelled in a convoy of armoured personnel carriers to the Red Sea Mills on the eastern edge of Hodeida, which wriggled out of Huthi control into the hands of coalition-backed Yemeni forces just before the truce.

Armed Yemeni men raise their weapons as they gather near the capital Sanaa to show their support to the Shiite Huthi movement against the Saudi-led intervention on February 21, 2019. (AFP / Mohammed Huwais)

Armed Yemeni men raise their weapons as they gather near the capital Sanaa to show their support to the Shiite Huthi movement against the Saudi-led intervention on February 21, 2019. (AFP / Mohammed Huwais)What I saw in the battle-scarred granary was shocking — a mountain of wheat, enough to feed nearly four million starving people for a month. That’s thousands of metric tonnes of grain, lying there mouldering, while half the population is starving. Aid organisations had been unable to reach the site since September amid active combat.

The UN finally reached there in late February. Potentially many lives could have been saved had they got there sooner.

Government loyalists alleged the Huthis had been hoarding grain, creating artificial shortages and exacerbating famine-like conditions. When the Huthis controlled the mill, they accused coalition-backed forces of destroying food with indiscriminate air strikes.

Twisted beams of light filtered through the shrapnel and bullet holes in one of its warehouses, revealing how the heavily-contested site had been an active target. While I was there, a volley of close-range gunshots crackled through the complex. It was not possible to tell who was firing.

Soldiers scoured the vast complex with metal detectors amid fears rebels were sneaking in to plant new booby traps. A column of smoke snaked into the sky from Huthi positions less than a mile away. Pro-government loyalists said the rebels were burning tyres in a provocative move.

Just after we pulled out of Hodeida, the UN reported that mortar shelling at the mill had started a fire that left two food silos damaged.

A picture taken on August 8, 2018 during a trip in Yemen organised by the UAE's National Media Council (NMC) shows a view of the Red Sea coast in southwestern Yemen, south of Hodeidah province. (AFP / Karim Sahib)

A picture taken on August 8, 2018 during a trip in Yemen organised by the UAE's National Media Council (NMC) shows a view of the Red Sea coast in southwestern Yemen, south of Hodeidah province. (AFP / Karim Sahib) Damage on a building after a reported air strike by the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen's Huthi rebel-held capital Sanaa, December, 2017.

(AFP / Mohammed Huwais)

Damage on a building after a reported air strike by the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen's Huthi rebel-held capital Sanaa, December, 2017.

(AFP / Mohammed Huwais)

The head of a Yemeni development organization told me such attacks underscored a “Machiavellian” design to control food aid. In a country where more than 80 percent of the population relies on some form of humanitarian assistance daily, the side that controls such facilities wields greater political say on who gets fed. “Food is a weapon,” he said.

War-induced malnourishment is the result of such a deliberate obstruction of humanitarian assistance — the only lifeline for Yemenis. It is further exacerbated by the hobbled state of Yemen’s economy. War has caused a sharp spike in food prices and high levels of unemployment. Yemenis face two wars, many say—the first is the one that comes from bombs, landmines and air strikes. The second is the inflation war, which has devastated the purchasing power of ordinary Yemenis.

A Yemeni woman carries on her head the sack of grain that she received as food aid in the capital Sanaa, February, 2019.

(AFP / Mohammed Huwais)

A Yemeni woman carries on her head the sack of grain that she received as food aid in the capital Sanaa, February, 2019.

(AFP / Mohammed Huwais)Beggars congregate outside local markets that are stocked with an abundance of food—milk, fruits, vegetables, grain and meat. But prices have skyrocketed, making even basic food staples beyond the reach of ordinary Yemenis. Many are forced to live on boiled leaves.

A girl from a poor Yemeni family living in a garbage dump in an impoverished coastal village on the outskirts of the Yemeni port city of Hodeidah, looks through scraps of bread on October 9, 2016. (AFP / Stringer)

A girl from a poor Yemeni family living in a garbage dump in an impoverished coastal village on the outskirts of the Yemeni port city of Hodeidah, looks through scraps of bread on October 9, 2016. (AFP / Stringer) Stalls of plenty at a market in the Huthi-held Red Sea port city of Hodeida on December 14, 2018. (AFP / Abdo Hyder)

Stalls of plenty at a market in the Huthi-held Red Sea port city of Hodeida on December 14, 2018. (AFP / Abdo Hyder)

Yemen appears to be a nation in collective despair. A bellwether of sorts is the new spike in weddings despite the war. Weddings are a way to survive—it fetches the groom’s family a bride price and a dignified way to alleviate their suffering.

For the war-weary population of Hodeida, the choices are equally stark — they are torn between a bloody truce with violations on both sides or the prospect of all-out fighting that could unleash famine.

Civilians are trapped in squalid camps close to Hodeida and fear returning to their homes and farm lands despite the truce. People see peril and hopelessness at every turn, with no clear way out. Many accused the rebels of seeding them with mines — often camouflaged as rocks — as punishment for fleeing to government areas.

Yemenis who were displaced from Hodeida receive humanitarian aid donated by a Turkish NGO in the northern district of Hajjah province on August 6, 2018. (AFP / Essa Ahmed)

Yemenis who were displaced from Hodeida receive humanitarian aid donated by a Turkish NGO in the northern district of Hajjah province on August 6, 2018. (AFP / Essa Ahmed) Yemenis dig graves for children who where killed when their bus was hit during a Saudi-led coalition air strike in the Huthi rebels stronghold province of Saada, August 10, 2018.

(AFP / Stringer)

Yemenis dig graves for children who where killed when their bus was hit during a Saudi-led coalition air strike in the Huthi rebels stronghold province of Saada, August 10, 2018.

(AFP / Stringer)

The past has shown Yemenis a woefully familiar pattern — ceasefire leads to more war. A common refrain among civilians and military officials is "mafi hudna" — Arabic for "no truce".

Despite the truce, war-wounded people pour into hospitals. I saw young pro-government fighters, slinging rifles, crowding the emergency room of a frontline hospital. They stood anxiously over medics working to save their comrades — men smeared with dirt and blood, their bodies riven with shrapnel or bullets.

With frequent skirmishes, many embittered fighters evinced frustration that the truce halted their offensive just as they got tantalisingly close to the rebel-held Hodeida port. A sentiment echoed by many was that military action was the only solution. They were adamant — the other side must be wiped out, whatever it takes.

"Even if 50,000 people die (if war resumes), so what?" a pro-government loyalist told me matter-of-factly. "We will finish them (Huthis) off forever."

Never mind that if the truce breaks down, the battle for Hodeida would almost certainly be protracted and destructive — and will almost certainly precipitate famine.

Back at the children’s ward, a doctor tells me the parents of the emaciated baby I met are among the lucky ones. Many others can't make it to hospital and are forced to helplessly watch their hungry children wasting away, unable to do anything about it.

I imagined that baby in a happier, healthier scenario— probably in pre-school, full of life and joy, a whirl of noise and mischief. But instead, the child is on a hospital bed, fighting for breath.

If only a feast, or even a tiny sliver of it, was laid out for children like him.

A Yemeni boy kicks plays football with friends and neighbors in the capital Sanaa, April, 2018. (AFP / Mohammed Huwais)

A Yemeni boy kicks plays football with friends and neighbors in the capital Sanaa, April, 2018. (AFP / Mohammed Huwais) A Yemen boy suffering from severe malnutrition lies on a bed at a clinic in the western province of Hodeidah, November, 2018.

(AFP)

A Yemen boy suffering from severe malnutrition lies on a bed at a clinic in the western province of Hodeidah, November, 2018.

(AFP)