Brexit borderlands

Along the Irish border -- Peace came to Northern Ireland when I was just seven years old -- I have no memory of the bitter violence that defined three decades of life in the British province.

Twenty years on, I spent a week travelling its 500-kilometre border with the Republic of Ireland to speak to locals about the fear that Brexit could bring back the bad old days.

What I found in the borderlands was a community both uniquely resilient and uniquely vulnerable to the threat of imminent disruption.

Accompanied by video journalist Will Edwards, my journey started with a trip north from my home in Dublin to the border at Newry.

The British army used to call this rolling countryside "bandit country" because of the sniper and bombing attacks.

One resident recalled that soldiers named local counties after regions in America's Wild West.

An aerial view of the Culicagh mountain boardwalk, which threads along the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, February 22, 2019, Florencourt, Northern Ireland.

(Getty Images/AFP / Charles Mcquillan)

An aerial view of the Culicagh mountain boardwalk, which threads along the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, February 22, 2019, Florencourt, Northern Ireland.

(Getty Images/AFP / Charles Mcquillan)At a farm bisected by the border in South Armagh, we find a roadside warning: "Thieves and thugs will be dealt with by the community." It's hard to imagine such a sign elsewhere in Britain.

In Dublin a few weeks earlier, a former Irish soldier told me locals believe the British army installed cameras in the hills when they dismantled watchtowers which used to perch over border communities.

It seems unlikely to me -- but more evidence of the trauma left imprinted on an area once under constant supervision.

Later I'm reminded of a story I read claiming that Northern Ireland suffers from the highest rate of PTSD in the world.

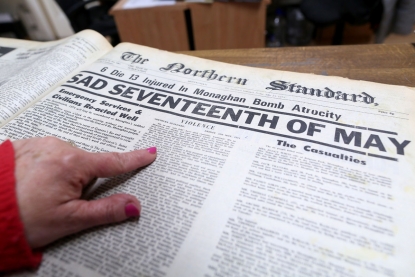

A front page headline about the Monaghan bombings is pictured at the local newspaper office, The Northern Standard, in the Irish border town of Monaghan on March 5, 2019. (AFP / Paul Faith)

A front page headline about the Monaghan bombings is pictured at the local newspaper office, The Northern Standard, in the Irish border town of Monaghan on March 5, 2019. (AFP / Paul Faith)Everywhere in the region, stories about the past are offered up with a mix of dark humour and stoicism.

After probing one man -- the target of two attempted assassinations -- for an insight into what it was like during "The Troubles", he eventually admits: "It was a bit annoying at times."

Quizzed on how they would react to the return of border controls, some locals believe talk of checkpoints is all hype, others believe they would handle them day by day, just like last time.

People walk along the streets of the town centre, near a Memorial to the Monaghan bombings, in the Irish border town of Monaghan on March 5, 2019. (AFP / Paul Faith)

People walk along the streets of the town centre, near a Memorial to the Monaghan bombings, in the Irish border town of Monaghan on March 5, 2019. (AFP / Paul Faith)The 1998 Good Friday peace deal turned the border itself into a strange kind of grey zone -- present on maps but invisible to the naked eye.

Only a crease in the tarmac and a change in speed limits from miles to kilometres per hour offer clues you are entering a different territory.

Many of our visits to the dividing line saw us checking online for a sign of where one country ended and another began.

Members of the anti-Brexit campaign group "Border Communities Against Brexit," dressed as British Army soldiers, pose with a wall installed on a road crossing the border between Northern Ireland and Ireland, during a demonstration in Newry, Northern Ireland, on January 26, 2019.

(AFP / Paul Faith)

Members of the anti-Brexit campaign group "Border Communities Against Brexit," dressed as British Army soldiers, pose with a wall installed on a road crossing the border between Northern Ireland and Ireland, during a demonstration in Newry, Northern Ireland, on January 26, 2019.

(AFP / Paul Faith)Somewhere in this blurred frontier between the United Kingdom and Ireland is my own story.

Last month, I turned in an application for Irish citizenship. As a British native with Irish grandparents I am entitled to a passport allowing me to remain an EU citizen after Brexit.

Now I too find myself making an effort to find a home in that space astride the two territories.

(AFP / Daniel Leal-olivas)

(AFP / Daniel Leal-olivas)