In the belly of the beast

Aboard the Vigilant -- “There is a chance to spend 24 hours aboard an SSBN, are you available?” When I receive the message from the French Navy, I don’t even take the time to think about it. A chance to spend a day inside a nuclear ballistic missile submarine? “Yes, of course,” I answer right away.

I get giddy just thinking about it. A chance to see from the inside one of the most secret places in the French military. What will it be like aboard this metal monster as it carries its nuclear warhead load 350 meters below the surface of the sea? I think about Nathalie Guibert, a journalist at the Le Monde newspaper, who spent a month aboard a French submarine in 2014. The title of the book that she then wrote about the experience was “I wasn’t welcome.” Oh well, I’ll take things as they come.

This photo taken on October, 2016 shows the French Navy's strategic nuclear submarine Le Vigilant at its base of L'Ile Longue. (AFP / Valérie Leroux)

This photo taken on October, 2016 shows the French Navy's strategic nuclear submarine Le Vigilant at its base of L'Ile Longue. (AFP / Valérie Leroux)Hedwige, the navy communications officer who is to accompany me on the trip, gives me only rudimentary instructions -- don’t bring aerosol toiletries (the air circulation system can’t recycle them), no electronics. Nothing too intimidating. The only thing that gives me pause is how I’m going to get off once my visit is over -- apparently I will spend 15 minutes at the end of a cable as it hoists me from the sub to a helicopter above. Even people accustomed to the procedure make a face when describing it, which does little to reassure me. But it seems a small price to pay.

The Vigilant before taking the plunge.

(AFP / Valerie Leroux)

The Vigilant before taking the plunge.

(AFP / Valerie Leroux)To get onto the sub, I first board a Navy speedboat in the town of Brest, in France’s northwest. We take off for l’Ile Longue, an island where the nuclear ballistic missile submarines are stationed, away from prying eyes. Nets underwater, surveillance cameras, commandos -- the approach to the island is under tight security. People without proper authorization are definitely not welcome here. At the end of the island I see the somber mass of metal that will soon plunge, with me along, under the waves. The Vigilant is one of four ballistic nuclear submarines of the French Navy, which also has six nuclear attack submarines (SSN) that are based in Toulon in the Mediterranean.

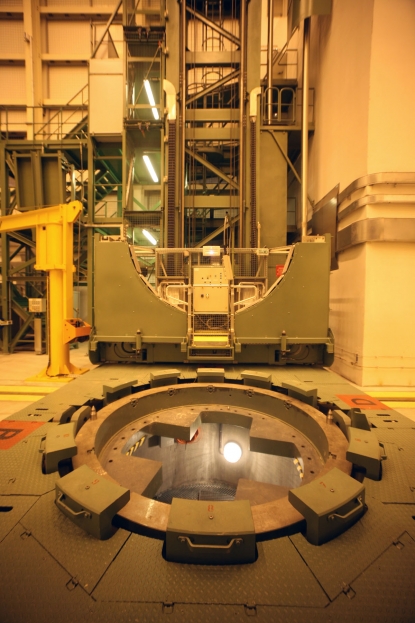

The assembly zone of a French Navy ballistic missile, March 2007.

(AFP / Marcel Mochet)

The assembly zone of a French Navy ballistic missile, March 2007.

(AFP / Marcel Mochet)L’Ile Longue is a veritable beehive, with its engineers, mechanics and sailors. The closer we get to the Vigilant, the busier the activity becomes. The crew is making final preparations before heading out to sea, where the sailors will spend 70 days. To get onboard, you walk along the bridge between the shore and the sub, climb onto the “kiosk,” a turret that hangs above, and slip into the belly of the beast through an opening 80 centimeters in diameter.

Before taking the plunge. (AFP / Valérie Leroux)

Before taking the plunge. (AFP / Valérie Leroux)For the first few moments onboard, the air seems to get thinner and you get a sense that it’s harder to breathe. Then, bit by bit, your breathing becomes more and more normal. But you’ll have to get used it to. When down in the depths, the air onboard is manufactured and recycled.

The submarine slowly takes off, as the crew performs the last tests and adjustments. A helicopter and a patrol boat accompany it and will do so as long as it remains on the surface.

Among the crew, each man is focused on his task. One of the sailors is on his first voyage. His movements are calm and precise. “We’ve been training for six months,” he tells me. “The majority have already been on patrol, so they have prepared the ones who haven’t.”

The Vigilant control room. (AFP / Valérie Leroux)

The Vigilant control room. (AFP / Valérie Leroux)What do these men think at this moment, knowing that they will be cut off from the outside world and their homes for more than two months? The answer is near unanimous: “We are doing what we chose to do. The hardest part is for the wife or girlfriend, who remain behind and have to take care of everything while we're gone.”

The navigation panel. (AFP / Valérie Leroux)

The navigation panel. (AFP / Valérie Leroux)I have just congratulated myself on having quickly acclimatized to this world, when suddenly I am hit by a wave of sea sickness. How can a boat 140 meters long and weighing 15,000 tonnes bob on the waves? An officer tells me, not without malice and satisfaction at my suffering: “With its smooth, round shell, it floats like a cork.”

There is nothing to do except to either lie down or take medicine that will make you drowsy. Some sailors wear anti-sea sickness patches behind their ears. But to be effective those had to be put on before departure. The misery will last for hours, as long as the Vigilant remains on the surface.

But as soon as it plunges into the depths, the nausea disappears all at once, as if by magic.

Checking the provisions. (AFP / Valérie Leroux)

Checking the provisions. (AFP / Valérie Leroux)The crew very quickly finds its rhythm, between tours of duty, meals and rest. All sounds onboard become muffled -- the submarine is supposed to glide through the depths undetected and all noise compromises that, makes it vulnerable to sonar detection systems. So all noise onboard is muffled, from the humm of the engines, to the opening of hatches.

For 24 hours, I follow the rhythm of the sailors, trying to understand what drives them, to get a glimpse into their secretive world.

“We live here like in a little village, without really realizing that we are under water,” says 33-year-old Bertrand, in charge of torpedos.

Do they have a sense of being the bearers of the Apocalypse, since their submarine is carrying nuclear warheads capable of destruction equivalent to hundreds of Hiroshimas? “Every person has to ask himself ‘and if one day we have to fire?’ Whoever answers ‘no, I’m not ready to do that’ has no business being here,” William, the first officer, tells me calmly.

In the ballistic missile compartment section.

(AFP / Valérie Leroux)

In the ballistic missile compartment section.

(AFP / Valérie Leroux)Life on board seems quite comfortable. There is more than enough space, with two or three beds in a row, a welcoming cafeteria and numerous toilets and showers. The SSBN ballistic submarines are the Cadillacs of the sea, compared to the much smaller SSN attack subs, or the next generation of attack subs, the Barracudas, due out next year.

Torpedoes and veggies -- examining the fruits and vegetables stored in the torpedo room.

(AFP / Valérie Leroux)

Torpedoes and veggies -- examining the fruits and vegetables stored in the torpedo room.

(AFP / Valérie Leroux)Women will be able to serve on French submarines, but only on the SSBNs, starting from next year. Will this revolution cause waves in such confined quarters? I ask the crew.

“The Navy admitted women officers 25 years ago,” Cyril de Jaurias, the commander of the Vigilant, tells me. “It wasn’t necessarily easy, but the Navy handled it and it will handle this as well.”

The Vigilant baker.

(AFP / Valérie Leroux)

The Vigilant baker.

(AFP / Valérie Leroux)I have to say that in my one day onboard I did not feel any resentment. Neither I nor Hedwige, the communications officer who accompanied me, felt intimidated at any moment. But we of course stayed for only a day…

Before we leave, we have to go through a baptism ritual -- I have to honor the fraternity of sailors and the sea by drinking a glass of pure seawater. Then I am handed a parchment that attests that I have penetrated into the kingdom of Neptune.

To drop off its visitors, the submarine resurfaces. The helicopter that will hoist us up is already hovering above. We will go from the depths of the sea to the heights of the sky. I struggle into an enormous orange jumpsuit that will keep me bobbing in the waves should the cable hoisting me unexpectedly break.

When you emerge from the belly of the beast the first thing that hits you is the fresh air. I have just enough time to glance at the stern ocean and at the cable hanging down from the helicopter. Then an invisible force pulls me up and the Vigilant becomes smaller and smaller. Eventually it disappears again into the depths, where it and the 110 men onboard will remain for another 69 days.

This blog was translated by Yana Dlugy in Paris.

The Vigilant heading out to sea. (AFP / Valerie Leroux)

The Vigilant heading out to sea. (AFP / Valerie Leroux)