Davos: It's good to talk

Davos, Switzerland -- My first trip to Davos came via a lucky break -- of my boss's leg that is.

As he called me up as an emergency replacement, he said: "If I'm going to give up my annual skiing holiday, you'd better do a good job."

And as I left for Switzerland, my colleagues joked: "Don't get too drunk at the champagne receptions."

Davos, January, 2018. (AFP / Miguel Medina)

Davos, January, 2018. (AFP / Miguel Medina) Davos, January, 2019. (AFP / Fabrice Coffrini)

Davos, January, 2019. (AFP / Fabrice Coffrini)

That's the public perception of the World Economic Forum in the stunning Swiss ski village of Davos: corporate fat cats, politicians and journalists on a ski junket followed by evenings quaffing bubbly.

Here's the thing: that's not too far from the truth! But for lowly journalists -- especially from news agencies like AFP trying to cover as many events as possible -- it's also one of the toughest assignments you can get.

Davos, January, 2019. (AFP / Fabrice Coffrini)

Davos, January, 2019. (AFP / Fabrice Coffrini)Everything -- really everything -- depends on your access badge. The so-called "reporting press" have yellow badges, allowing them into the main conference centre and the press room, where most of the set-piece speeches are piped into.

What this means in practice is that a yellow badger is pretty well confined to the press room, cranking out thousands of words per hour as a succession of world leaders takes to the stage to pontificate about world affairs.

Davos press room, January, 2004. (AFP / Eric Feferberg)

Davos press room, January, 2004. (AFP / Eric Feferberg)Being Davos, "panel sessions" of five people typically mean five national leaders. A session on Europe's future, for example, might feature the French president, German chancellor and president of the European Commission -- meaning you can't switch off for one minute.

I remember once remarking to a colleague that if any one of the speakers I had on my 'to-do' list came to my home bureau (Berlin at the time), it would be the biggest event of my week: at Davos, there were five such speakers on the same panel.

Super panel -- (L to R) Britain's Prime Minister David Cameron, Federal Chancellor of Germany Angela Merkel, Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono and World Trade Organization chief Pascal Lamy attend a session in January, 2011. (AFP / Fabrice Coffrini)

Super panel -- (L to R) Britain's Prime Minister David Cameron, Federal Chancellor of Germany Angela Merkel, Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono and World Trade Organization chief Pascal Lamy attend a session in January, 2011. (AFP / Fabrice Coffrini)A lot of time is also spent chasing curveballs. News breaks somewhere in the world and the chances are that the key person to talk to about it is in Davos so the dreaded call comes through from editors in Paris: 'Do you think you could just track down the Azerbaijani culture minister?'

One year, an unfortunate colleague spent a whole chilly day waiting for Britain's Prince Andrew to question him over the latest allegations he had sex with an under-aged girl.

Britain's Prince Andrew gestures during a reception at Davos, January, 2015. (AFP / Michel Euler)

Britain's Prince Andrew gestures during a reception at Davos, January, 2015. (AFP / Michel Euler)On the other hand, the fact that everyone is squished together in one place has its advantages -- a colleague once ran into the then Eurogroup president in the corridor. “Let’s walk and chat,” he said when she asked him for an interview. It took about five minutes to get enough material for an alert, urgent and an update of the main bar.

But what all members of the press corps aspire to is the coveted white badge. Reporters with white badges can take part in the scores of side sessions, off-the-record briefings and cozy chats with CEOs, ministers and global experts.

White badges are in very short supply for media organisations -- AFP has two and even those are hard-earned. I finally graduated after three trips to Davos (again, I think someone was ill) and it changed everything.

Because in fact what is interesting at Davos are not the grand speeches by world leaders -- in fact they rarely make news -- but the quirky sideshows that produce much livelier copy.

Combo of four pictures German Chancellor Angela Merkel joking with Irish singer star Bono at the World Economic Forum in Davos 25 January 2006. (AFP / Fabrice Coffrini)

Combo of four pictures German Chancellor Angela Merkel joking with Irish singer star Bono at the World Economic Forum in Davos 25 January 2006. (AFP / Fabrice Coffrini) US actor Matt Damon at Davos, January, 2017. (AFP / Fabrice Coffrini)

US actor Matt Damon at Davos, January, 2017. (AFP / Fabrice Coffrini)

Discussions on space travel, say, with the four leading global experts in the field. Autonomous vehicles with the heads of the world's top car companies. And because most of these sessions are off-the-record, leaders actually say what they think.

At one Davos, crowds deserted a speech by Iranian President Hassan Rouhani for a session on meditation led by Hollywood actress Goldie Hawn.

All alone -- Iranian President Hassan Rouhani on the stage in Davos, January, 2014.

(AFP / Eric Piermont)

All alone -- Iranian President Hassan Rouhani on the stage in Davos, January, 2014.

(AFP / Eric Piermont)Again, this being Davos, the vox pops you end up doing as a journalist are a little unusual. Looking back on my story about the Goldie Hawn event, I realised I approached a random member of the audience to ask his opinion. After a brief interview, I asked for his name: Crown Prince Haakon of Norway.

US actress Goldie Hawn at Davos, January, 2014. (AFP / Eric Piermont)

US actress Goldie Hawn at Davos, January, 2014. (AFP / Eric Piermont) Crown Prince Haakon of Norway at Davos, January, 2011. (AFP / Eric Piermont)

Crown Prince Haakon of Norway at Davos, January, 2011. (AFP / Eric Piermont)

I defy anyone attending Davos not to feel slightly self-important at times as you rub shoulders with the great and the good.

The Marine One helicopter carrying the US president comes in to land in Davos on January 25, 2018. (AFP / Nicholas Kamm)

The Marine One helicopter carrying the US president comes in to land in Davos on January 25, 2018. (AFP / Nicholas Kamm)One AFP journalist once found herself at the annual dinner organized by George Soros sitting next to a very courteous older gentleman whom she just couldn’t place. A glance at his badge and a quick discreet search on her smartphone revealed that he just happened to be a Nobel Economic laureate.

Sliding down the icy main street one night with a colleague from Brussels, he stopped to greet a young man coming in the opposite direction and we had a pleasant, if cold, chat. "Who was that?" I asked. "Prime Minister of Luxembourg," came the response.

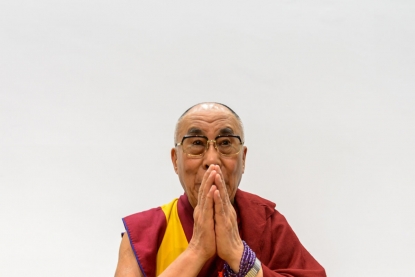

Davos is a place where you can go the men's toilets and find yourself standing next to the unmistakable form of the Dalai Lama -- as happened on my first trip.

The Dalai Lama acknowledges the audience after a press conference during his visit at the Swiss House of Parliament on April 16, 2013 in Bern. (AFP / Fabrice Coffrini)

The Dalai Lama acknowledges the audience after a press conference during his visit at the Swiss House of Parliament on April 16, 2013 in Bern. (AFP / Fabrice Coffrini)However, my favourite Davos "name drop" story is apocryphal but supposedly happened to a colleague of mine from Bloomberg, who somehow managed to wangle an invite to a party held by U2 frontman Bono.

Understandably, he assumed there would be hundreds there but arrived to find to his horror that it was a very intimate setting. A quick look around the dozen or so guests: oh, there's Bill Clinton. Ah, Bill Gates, and so on.

Melinda and Bill Gates at a Davos session, January, 2015. (AFP / Fabrice Coffrini)

Melinda and Bill Gates at a Davos session, January, 2015. (AFP / Fabrice Coffrini)Being a huge U2 fan, my friend finally plucked up the courage to approach Bono and ask him about one of the band's songs that was never recorded and holds a mythical reputation among hardcore fans.

Bono (apparently) replied: "Oh my God, I can't believe you know about that song. Hang on, I'll just get my guitar and sing it for you", leaving this journalist agog as his hero seranaded him.

Sounds too good to be true but I'm inclined to believe it: it's exactly the sort of thing that would happen at Davos.

Bono at Davos in January, 2008. (AFP / Fabrice Coffrini)

Bono at Davos in January, 2008. (AFP / Fabrice Coffrini)Not everyone is a fan. A younger AFP colleague came back furious at all the staff from NGOs, charities and environmental groups living it up in Davos -- where a pizza can easily cost you $50 -- while preaching about global poverty.

Swedish youth climate activist Greta Thunberg at Davos, January, 2019. (AFP / Fabrice Coffrini)

Swedish youth climate activist Greta Thunberg at Davos, January, 2019. (AFP / Fabrice Coffrini)Another gruffly sniffed that the "quality of debate here is very poor intellectually."

"Five days of working for 14 hours, drinking for eight and sleeping for two," was how one attendee described it to me as we descended the mountain in the bus through what is surely one of the world's most beautiful commutes.

Davos, January, 2018. (AFP / Fabrice Coffrini)

Davos, January, 2018. (AFP / Fabrice Coffrini)The forum has drastically changed since it first began in January 1971. When one of my colleagues covered it for the first time in 1985, she was told of the assignment a week before and had no problems getting accreditation or booking a hotel room. She was the only journalist there from AFP.

Nowadays, you need to put in for accreditation and hotel bookings months in advance (one year, AFP bookings were lost and the team had to bunk with the Swiss army at an old disused sanatorium -- so after 14-hour days, they schlepped up a hill, crossed barbed wire gates, marched past an ammunition store to get to their quarters, complete with shared bathrooms.) And the AFP team at the event now includes some dozen journalists from text, photo and video, producing in three languages.

As Davos turns 50, is it still relevant? Was it ever?

It's undoubtedly a talk shop -- despite the furious wheeling and dealing that gets done over the canapes and chilled fizz.

But in this uncertain and turbulent world, I can't help thinking that a cozy chat in a ski resort might not be such a bad thing.

Shimon Peres (R), President of Israel, talks next to Palestinian Prime Minister Salam Fayyad on January 26, 2012 at the World Economic Forum (WEF) in the congress center of the Swiss resort of Davos. (AFP / Vincenzo Pinto)

Shimon Peres (R), President of Israel, talks next to Palestinian Prime Minister Salam Fayyad on January 26, 2012 at the World Economic Forum (WEF) in the congress center of the Swiss resort of Davos. (AFP / Vincenzo Pinto)