As memories fade

Jerusalem - How do you interrupt an Auschwitz survivor in an interview as he strays way off topic? How do you balance your need to get his personal story with his need to tell you the history of the Holocaust in a world where the memory of the Nazi genocide is fading further and further into history? What imprint does hearing stories of evil over and over again leave on you?

Ahead of the 75th anniversary of the liberation of the notorious death camp by Soviet troops, the AFP team in Jerusalem interviewed 11 survivors to produce a multimedia package.

Each journalist faced his own difficulties in doing so. Text reporter Michael Zeev Blum, who grew up in a world where the memory of the Holocaust was ever-present, searched for details of his grandfather whose name he bears. Photographer Menahem Kahana couldn’t help but hear echoes of his parents. Bureau chief Guillaume Lavallee kept thinking of how to keep a handle on and do justice to the heartbreaking material. Video journalist Ahikam Seri heard the stories in a new light and saw something he hadn’t noticed before.

Michael Blum

Text journalist

I never met my grandfather but he has been a towering presence in my life ever since I was born. As has the Holocaust.

An Auschwitz survivor, my grandfather Wolf Magnichever died a few years after the war. His health had been too damaged in the camps. My middle name comes from him (Zeev means “wolf” in Hebrew).

My mom was obsessed by the Holocaust. When I was little, she showed me the yellow star that her father wore on the streets of Paris before being deported, told me stories of what happened to the Jews during World War II.

When I wrote my very first news story at the age of 10, for my Paris elementary school newspaper, it was about my grandfather and the Holocaust.

An aerial picture taken on December 15, 2019 in Oswiecim, Poland, shows a view of the railway entrance to former German Nazi death camp Auschwitz II - Birkenau with its SS guards tower. The site has been turned into a museum and memorial site. (AFP / Pablo Gonzalez)

An aerial picture taken on December 15, 2019 in Oswiecim, Poland, shows a view of the railway entrance to former German Nazi death camp Auschwitz II - Birkenau with its SS guards tower. The site has been turned into a museum and memorial site. (AFP / Pablo Gonzalez)I have written a lot on the subject over the years. Ahead of the 75th anniversary of the Auschwitz liberation, I thought it would be a good idea to interview some survivors, since time is running out -- with each year there are less and less.

I proposed doing a regular story. But my editors liked the idea and eventually it morphed into a multimedia project. I knew then that, more than 40 years after that article for the school newspaper, I had the opportunity to do one of the most important pieces of journalism of my entire career.

And throughout this story, Wolf was by my side. I was born after he died and my mother told me he never talked about the camp. But now I had the chance to -- maybe, just maybe -- learn what it was like there for him.

Every time I was sitting in front of someone, asking them questions and listening to their tales, I tried to picture my grandfather. He must have done many of the same things. I asked every single one if they had known him. They hadn't. But when they told me of ways they survived, I imagined that my grandfather had survived in many of the same ways as well.

(COMBO) This combination of pictures created on January 11, 2020 shows (L to R) Holocaust survivor Menahem Haberman, 92, poses with a picture of himself after the war,

Holocaust survivor Danny Chanoch, 87, poses with a picture of him and his elder brother Uri after the war, Holocaust survivor Dov Landau, 91, shows pictures of his parents killed by the Nazis, Holocaust survivor Szmul Icek shows a picture of his parents killed by the Nazis, pose during a photo session. (AFP / Menahem Kahana)

(COMBO) This combination of pictures created on January 11, 2020 shows (L to R) Holocaust survivor Menahem Haberman, 92, poses with a picture of himself after the war,

Holocaust survivor Danny Chanoch, 87, poses with a picture of him and his elder brother Uri after the war, Holocaust survivor Dov Landau, 91, shows pictures of his parents killed by the Nazis, Holocaust survivor Szmul Icek shows a picture of his parents killed by the Nazis, pose during a photo session. (AFP / Menahem Kahana)This project was really a privilege for me. Most of the interviews were very hard. But after it was over, I didn’t have the feeling of ‘ok, that’s enough.’ I would like to go back and talk to these people, to learn more, to just spend time with them. I suppose for me it’ll be a bit like spending time with my grandfather.

And there were also bright spots. Like when Danny Chanoch told us that after you’ve lived in Auschwitz, you’re weren't going to complain about anything else in life. “I’m not scared of anything,” he said.

Danny Chanoch. (AFP / Menahem Kahana)

Danny Chanoch. (AFP / Menahem Kahana)Doing this story, I often had tears in my eyes. But the only time I cried was with Helena Hirsch. Because of an accident a few years back, she cannot walk. Since she lives in a fourth-floor apartment in a building without an elevator, that means that she can’t leave her home. So she is stuck in there, with her memories.

Her grown granddaughter takes care of her and she was there during our interview. Helena was telling us of how her granddaughter went to visit Auschwitz, something that Helena herself never did. “When she was there, she was incredibly brave, like I was brave when I was there,” Helena told us. It was such a victory for her that her granddaughter went there, to that hell hole, as a free woman, an Israeli.

“I am so proud of her,” she said, looking lovingly at the young woman. And that’s when I cried. I suppose that deep down, I hoped that my grandfather was also proud of me, for telling the world the story he never did.

(AFP / Menahem Kahana)

(AFP / Menahem Kahana)Menahem Kahana

Photographer

I manage to keep my distance from stories that I cover. Maybe it’s because I’ve been a journalist in Israel for 30 years and we have had so many bad things happen here. And for the most part, I managed to do it again with this story. But I can tell you that I’ll remember this one.

Of course the subject is important. When you live in Israel, the Holocaust is a big part of your life. We learn about it in school, in the army, we all go to Yad Vashem, we all literally stop in our tracks for a minute of silence on Holocaust Remembrance Day. So it becomes a part of you, you can’t just ignore it.

Holocaust survivor Saul Oren, shows his arm with the Auschwitz prison number 125421, during a photo session at his home in Jerusalem in December 2, 2019. Born in Poland in 1929, he was chosen by a Nazi doctor to undergo medical experiments and was transferred from Auschwitz to a concentration camp in Germany, to be freed in 1945. After the war he found his brother who had been with him at Auschwitz, and emigrated to Israel. (AFP / Menahem Kahana)

Holocaust survivor Saul Oren, shows his arm with the Auschwitz prison number 125421, during a photo session at his home in Jerusalem in December 2, 2019. Born in Poland in 1929, he was chosen by a Nazi doctor to undergo medical experiments and was transferred from Auschwitz to a concentration camp in Germany, to be freed in 1945. After the war he found his brother who had been with him at Auschwitz, and emigrated to Israel. (AFP / Menahem Kahana)The story wasn’t as big a part of my home as it was in others'. My parents were children in a Romanian village during the war. They wore the yellow stars of David. But then they were forced to leave and walk somewhere else, and then the war was over. So technically I guess they survived the Holocaust, but they were lucky, they didn’t end up in a concentration camp. They didn’t live through that trauma. They didn’t really talk about it. My mother told me a few stories about Germans in their village, but it wasn’t anything dramatic.

But despite this, this story was personal for me as well. When we were interviewing people, I kept comparing them to my parents. They passed away over the past several years and the people we were interviewing reminded me of them. Most of the people we interviewed came from Europe, like my parents. They were old, like my parents in their last years. They looked like my parents, they talked like my parents, they behaved like my parents. In a way, this was my parents’ story too. They were never in a death camp, of course. But that was just sheer luck. They could have been.

Holocaust survivor Schmuel Bogler, 90, poses with his wife Shoshana during a photo session at his home in Jerusalem, on December 12, 2019. Born in Hungary in 1929, the youngest of ten children was deported to Auschwitz with a large part of his family, and escaped death by being sent to a labour camp with one of his brothers, with whom he survived the Nazi Death March. (AFP / Menahem Kahana)

Holocaust survivor Schmuel Bogler, 90, poses with his wife Shoshana during a photo session at his home in Jerusalem, on December 12, 2019. Born in Hungary in 1929, the youngest of ten children was deported to Auschwitz with a large part of his family, and escaped death by being sent to a labour camp with one of his brothers, with whom he survived the Nazi Death March. (AFP / Menahem Kahana)Some moments were very hard. Like Malka Zaken, the one with the dolls. It was hard to hear from her. I remember we walked in and she was holding a doll in her hands. Her house was full of them. Dozens of them, on the bed, everywhere. We asked her, “why do you have them?” And she answered that when she was little, her mother used to give her dolls, so they remind her of a happier time, when she was a little girl who still had her mother. That was hard.

Malka Zaken, 91, poses with her dolls in Tel Aviv, December 16, 2019. Born in Greece, Malka was 12 when she was deported to Auschwitz.

(AFP / Menahem Kahana)

Malka Zaken, 91, poses with her dolls in Tel Aviv, December 16, 2019. Born in Greece, Malka was 12 when she was deported to Auschwitz.

(AFP / Menahem Kahana)But some moments were light. They were beautiful.

Like when I took Danny Chanoch to Jerusalem. I had to come back to his house to photograph him again because when I was there with the rest of the team, it was the first time I had used the studio and the light just didn’t turn out well. He agreed for me to come back. “But only if you take me to Jerusalem after,” he said. I said “all right.”

Turned out he wanted to go to Jerusalem for a bat mitzvah. It was the bat mitzvah of the granddaughter of his childhood friend. They grew up in the same village, they were both sent to Auschwitz, both survived, the friend eventually moved to the US and became a doctor, but they kept in touch. And now the friend had come to Israel to attend the bat mitzvah of his granddaughter, who lived here. I think they and I were the only two men there. You had a bunch of 12-year-old girls dancing and Danny Chanoch and his friend were sitting on the side, watching them and chatting. At one point, I asked them, like you do in these situations -- “what did you do at this age?” And they said: “We were in the camp.”

It was an amazing contrast: these two old guys who survived Auschwitz and the Holocaust, watching their grandchildren dancing and celebrating Judaism’s coming of age ceremony. In Israel.

Danny Chanoch, 87, poses with a photo on him and his older brother Uri after the war, during a photo session at his home in central Israel on December 10, 2019. Born in Lithuania, the two brothers were reunited in Italy after the war and together immigrated in 1946 to Palestine, then under the British mandate.

(AFP / Menahem Kahana)

Danny Chanoch, 87, poses with a photo on him and his older brother Uri after the war, during a photo session at his home in central Israel on December 10, 2019. Born in Lithuania, the two brothers were reunited in Italy after the war and together immigrated in 1946 to Palestine, then under the British mandate.

(AFP / Menahem Kahana)Guillaume Lavallee

Bureau chief

The sparkling eyes and black humor of Danny Chanoch got us on our way. One sunny November afternoon we showed up at the Israeli village where he lived to begin the project of interviewing survivors of the Auschwitz concentration camp ahead of the 75th anniversary of the camp’s liberation on January 27, 1945 by Soviet troops.

We went from one survivor to the next with a mini-studio, so that we could record the images and memories of each against the same background.

With his friendly nature, his jokes, his memories hanging on his walls and living in his heart, Danny Chanoch plunged us into our project with a startling remark. “I don’t know how I could have lived without Auschwitz,” he said.

Danny Chanoch did not cry at night, he was not defeated or cowed by the flashbacks. The death camps are part of him -- what he was and what he has become. And he can’t imagine his life otherwise.

It’s already odd enough to go into someone’s home and to install a mini-studio in their living room. Stranger still to ask them to recount not only their life, but to plunge them back into a hell that they’ve lived through. But although they differed in their approach to what had befallen them, we sensed in all a strong wish to transmit their experiences to future generations, to those to whom the Nazi genocide of the Jews can seem abstract. It is their duty, they felt, to tell the world what they had lived and survived the horrors that had befallen them.

Holocaust survivor Batcheva Dagan, whose entire family was killed, poses while showing her arm with the Auschwitz prison number 45554, during a photo session at her home in the Israeli town of Holon, south of Tel Aviv, on December 25, 2019. Born in Poland in 1925, she became a pioneer in the field of Holocaust education, and has dedicated her life to teaching. (AFP / Menahem Kahana)

Holocaust survivor Batcheva Dagan, whose entire family was killed, poses while showing her arm with the Auschwitz prison number 45554, during a photo session at her home in the Israeli town of Holon, south of Tel Aviv, on December 25, 2019. Born in Poland in 1925, she became a pioneer in the field of Holocaust education, and has dedicated her life to teaching. (AFP / Menahem Kahana)Some of them were veritable encyclopedias on the Holocaust itself -- we would ask them a question and they would answer for 30 minutes. Sometimes they would stray off topic, recounting history instead of their personal recollections. But how do you interrupt a Holocaust survivor? Do you raise your voice because the person, who is 90 plus, doesn’t hear that well?

Which is what happened with 94-year-old Shmuel Blumenfeld. “But don’t you want to know,” he said when we interrupted him once as he recounted a nearly day-by-day history of the Holocaust. How do you explain to him, without hurting his feelings, that we weren’t there to record the history of the Holocaust. We were there to find out how he survived it; how did he lead his life afterward, what did he want to pass on to future generations. So we had to steer him from one set of memories to another, so that we could get to the man inside, to what remained of him after the horror. I’m not sure we managed to achieve this every time, but that was our goal, our challenge.

Shmuel Blumenfeld, 94, at his home in Israel, November 28, 2019.

(AFP / Menahem Kahana)

Shmuel Blumenfeld, 94, at his home in Israel, November 28, 2019.

(AFP / Menahem Kahana)One of Shmuel Blumenfeld’s memories was meeting Adolf Eichmann, the mastermind of the “Final Solution.” Eichmann was captured by Israel’s Mossad spy agency in Argentina in 1960 and whisked out of the country to stand trial in Israel. He was found guilty of war crimes in a highly publicized trial in Jerusalem and hanged in 1962. Shmuel Blumenfeld was a guard at the prison where Eichmann was held. It was disturbing to hear Shmuel tell us in German about their encounter. It was as if he were reliving it, as if he had extracted the scene from a hiding place in his past.

Adolf Eichmann at the opening of his trial in Jerusalem, May 5, 1961. Sentenced to death, the mastermind of the "Final Solution" was executed on May 30, 1962.

(AFP files)

Adolf Eichmann at the opening of his trial in Jerusalem, May 5, 1961. Sentenced to death, the mastermind of the "Final Solution" was executed on May 30, 1962.

(AFP files)Several of the people we interviewed were on the verge of tears during the interviews, without actually crossing that line. We had to find a way to show the force and achievement of a people that march through history despite the adversity that relentlessly follows them.

And then there were those who had never before looked for publicity, who had never been in the spotlight. Like Szmul Icek. Following an accident several years back, he hasn’t been able to speak properly. He is able to just push a few words out. When he managed to push out “it’s not possible” as he took his neck with his hands, showing us the death around Auschwitz, all four of has had tears in our eyes. We all wanted to hug him. We felt the depth of emotion of a man whose parents and two sisters were killed by the Nazis. For a moment, it seemed like we were actually feeling his pain.

Holocaust survivor Szmul Icek shows his Auschwitz prison number 117568 on his arm, during a photo session at his home in Jerusalem on December 8, 2019. Born in Poland in 1927, he and two brothers survived while their parents and two sisters were killed in the Holocaust, and, in contrast to some survivors, he never returned to the camp after the war and avoids reading books on the subject. (AFP / Menahem Kahana)

Holocaust survivor Szmul Icek shows his Auschwitz prison number 117568 on his arm, during a photo session at his home in Jerusalem on December 8, 2019. Born in Poland in 1927, he and two brothers survived while their parents and two sisters were killed in the Holocaust, and, in contrast to some survivors, he never returned to the camp after the war and avoids reading books on the subject. (AFP / Menahem Kahana)Then there was Malka Zaken. When we met her, she was surrounded by dolls, hugging one tightly in her arms. “Don’t worry,” she told her, watching us. “They are not the Germans.” Her pain and trauma were crying out, bare in front of us. Same for Helena Hirsch who told us how she survived as a little girl in a concentration camp and how she managed to hide to avoid being sent to the gas chamber. It was like that horrified child from all those years ago reappeared in front of us.

Holocaust survivor Malka Zaken, 91, poses with a doll, a reminder of her childhood with her mother who was killed by the Nazis, during a photo session at her home in Tel Aviv on December 16, 2019. Born in Greece in 1928, she was 12 when she was sent to the death camp, assigned to fold the clothes of Jews killed in the gas chamber, and recalls the fear at Auschwitz. When the memories become too much, she turns to her dolls. (AFP / Menahem Kahana)

Holocaust survivor Malka Zaken, 91, poses with a doll, a reminder of her childhood with her mother who was killed by the Nazis, during a photo session at her home in Tel Aviv on December 16, 2019. Born in Greece in 1928, she was 12 when she was sent to the death camp, assigned to fold the clothes of Jews killed in the gas chamber, and recalls the fear at Auschwitz. When the memories become too much, she turns to her dolls. (AFP / Menahem Kahana)The weeks spent interviewing the survivors also filled us with an unfamiliar anxiety. What do we keep from all this? Each story was so strong and so heartbreaking, how do we put it all in one piece without betraying anyone? How to connect the individual histories? How to keep our distance?

As a journalist, I’m not going to write a story on Holocaust survivors the same way that I would write an ordinary feature. I’m not necessarily going to put the strongest element in the lead paragraph like I usually would. The survivors were like a chorus and each one had particularly strong points to share -- being separated from their parents, the hunger, the terror, the death marches, the search for justice, the pain of passing on their experiences, life afterward.

The tears non-shed and the deafening silences of the survivors of “the planet of ashes,” in the words of Israeli writer Yehiel Dinur, have left their trace in all of us, both during the interviews and after.

As banal as it may sound, we were heartened when we saw that our finished work -- our stories and images -- were shared thousands of times on social media. It was a re-affirmation that there is room in our world of clicks and short attention spans for an in-depth project, that there remains an awareness of the Holocaust. That -- as all of the people we interviewed fervently hope -- what happened to them will not be forgotten.

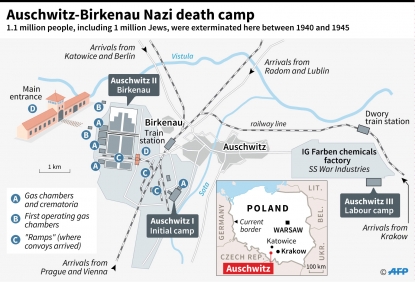

(AFP Graphics)

(AFP Graphics)Ahikam Seri

Video journalist

It wasn’t the first time I’d heard such stories. I’d heard such stories all my life. When you grow up in Israel, the Holocaust becomes part of your subconscious. Even if your family hadn’t gone through the Holocaust, you’ll have friends whose families have. Every Holocaust Remembrance Day you hear the stories, the horrifying details. First in school, when you’re a kid, then as an adult at ceremonies and on TV.

And it wasn’t the first time I’d met Holocaust survivors. Most people in Israel have met survivors as they have gone through life.

But this time I saw the stories -- and the people telling them -- in a new light.

From left to right, Auschwitz survivors: Szmuel Icek, Malka Zaken, Shmuel Blumenfeld, (top); Saul Oren, Batcheva Dagan and Menahem Haberman (bottom).

(AFP / Menahem Kahana)

From left to right, Auschwitz survivors: Szmuel Icek, Malka Zaken, Shmuel Blumenfeld, (top); Saul Oren, Batcheva Dagan and Menahem Haberman (bottom).

(AFP / Menahem Kahana)It wasn’t because I had to listen to the same stories over and over again. When you do video, you need to hear to the people being interviewed, to make sure the sound is right. Not just hear. You need to listen. Then you need to edit the footage, so you listen again and again. But that wasn’t the reason why I saw some things for the first time. It was the setting.

It’s one thing to hear the stories on TV, or at a ceremony, or on a screen. But when you hear them sitting right in front of the person who is talking, when you’re in their apartment, when you interact with them, it becomes an entirely different experience.

When you hear the story on TV, you are just watching the survivor. But when you’re in their home, when you see the person as they are today, when you see the difficulties they face today, you get a lot more context. Life is now, it’s not in the past or in the future. So the story teller is no longer just a survivor. They become a real person. It’s like entering a three-dimensional world from one where everything is flat.

When you’re with a survivor in their house for hours at a time, talking to them as you set up your equipment and then hearing them tell their tales, details begin to appear. From the little nuances, you can see this person’s ability to handle life around them. You start to really feel their character. Who is likely to cry, who is likely to laugh. And when you start to connect to a person like that, the stories begin to change. You can imagine what it was like. When you see a person handling something in the present, you get a much better sense of how they handled things in the past. So their stories really come alive.

When you hear about something that happened in a concentration camp on a screen, you are confined to that moment. You feel the pain, and fear, and sorrow, and terror. And that’s it. But when you hear it from an old woman sitting in her apartment, you know how it ended up.

When you see Helena with her granddaughter and the love that she is getting from her granddaughter today, you feel happy for her. She went through hell. But today she has such love.

Holocaust survivor Helena Hirsch shows her arm with the Auschwitz prison number A 20982, during a photo session with her granddaughter Rozi at her home in Israel's Beni Brak suburb east of Tel Aviv, on December 16, 2019. (AFP / Menahem Kahana)

Holocaust survivor Helena Hirsch shows her arm with the Auschwitz prison number A 20982, during a photo session with her granddaughter Rozi at her home in Israel's Beni Brak suburb east of Tel Aviv, on December 16, 2019. (AFP / Menahem Kahana)And even though I have heard the stories a thousand times and know the horrible details inside and out, some things I saw for the first time. Like when I listened to Avraham Binet talk about getting his tattoo.

Avraham has a way of saying things simply, as they were, with no filters. I guess that’s why I could relate to him easily, because I appreciate when people talk like that.

He was telling us the story of how he got his tattoo in Auschwitz, along with his brother and sister. The workshop where they tattooed people was mayhem. There was shouting, there was crying and there were gunshots. If the children cried when they got tattooed, the Nazis shot them (apparently the thinking went that if you weren’t tough enough not to cry when you got tattooed you weren’t tough enough to work). So little Avraham was terrified of crying. He didn’t want to die.

Holocaust survivor Avraham Gershon Binet, 81, shows his arm with the Auschwitz prison number 14005, during a photo session at his home in Bnei Brak on December 8, 2019. A six-year-old at the time, he didn't cry when the Nazis branded him with that tattoo. (AFP / Menahem Kahana)

Holocaust survivor Avraham Gershon Binet, 81, shows his arm with the Auschwitz prison number 14005, during a photo session at his home in Bnei Brak on December 8, 2019. A six-year-old at the time, he didn't cry when the Nazis branded him with that tattoo. (AFP / Menahem Kahana)And then his turn came to get tattooed. He was six years old. He clenched his fists and he clenched his jaw and he steeled himself life a six-year-old boy would. And he didn’t cry. And as the 81-year-old Avraham said it to us, he demonstrated what he meant -- the old man clenched his fists and jaw. “I did not cry. I did not cry. I am very strong. I don’t cry. I don’t cry.” I couldn’t tell if it was the young kid or the old man talking.

And I saw such pride in him. And it was a very touching, deep moment for me. Because in him I saw all the survivors and how tough they were to survive. And then their shame when they came here and they weren’t always welcomed very nicely because they were regarded as the weak Jewish people who went to the slaughter like sheep. Because that was often the attitude in Israel toward them. I know from a lot of stories the shame that they felt when they encountered it. After all they lived through.

And as Avraham Binet told us how he didn’t cry out when he got his tattoo, I saw his pride and I realized just how tough he was. It was like a purification of the survivors’ experience. All my life, I have been moved by the stories of the Holocaust. But this was new. I had never really understood this toughness.

This blog was written with Yana Dlugy in Paris.

AFP team at work. (AFP / Guillaume Lavallée)

AFP team at work. (AFP / Guillaume Lavallée)