Treading softly among ghosts

Culiacan, Mexico -- You would think that the one place where a Mexican drug baron could do you no harm is a cemetery. Where he is dead and buried. But in Mexico's dangerous and often surreal underworld, even the ghosts of cartel kingpins can haunt journalists.

As part of a series of stories on the 10th anniversary of the militarization of Mexico's drug war, I traveled to the northwestern state of Sinaloa with video journalist Daphne Lemelin and photographer Alfredo Estrella to visit a graveyard famous for housing majestic mausoleums where shadowy figures are interred.

As our car rolled into the Jardines del Humaya cemetery in Culiacan, the state's capital, our eyes widened as we stared at a mini-city of small mansion-like crypts with domes, castle-like towers and Greek-style columns. Few living Mexicans could afford such luxurious accommodations, which one expert said can cost around $300,000.

(AFP / Alfredo Estrella)

(AFP / Alfredo Estrella)The place may have looked serene, but our fixer, photojournalist Fernando Brito, warned us that we had to take precautions and shouldn't stay too long.

In Sinaloa, home of imprisoned drug cartel kingpin Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzman, people work as "hawks" (lookouts) for gangs and we suspected that we would be watched. Another concern was the possibility that a drug lord's relatives or henchmen could be visiting their fallen loved one at the same time.

Daphne and Alfredo took pictures as our car crept past a crypt that looked like a small chapel with columns and a large statue of Jesus Christ on top, but we stayed away from it when we saw a man loitering next to it.

(AFP / Alfredo Estrella)

(AFP / Alfredo Estrella)Fernando decided that we could stop and walk around a bit. A tomb that caught my attention looked like a modern apartment with glass doors. Pictures of a beautiful dark-haired woman -- in a cocktail dress or swimming in a pool -- hung on a wall in front of a leather sofa. An empty bottle of champagne was placed under one picture. Like most crypts, there was no name on the tomb to identify the deceased, but I later learned it was the final resting place of the girlfriend of a notorious Sinaloa cartel hitman.

(AFP / Alfredo Estrella)

(AFP / Alfredo Estrella)After a few minutes, Fernando said it was probably time to drive off to avoid drawing too much unwanted attention.

We had good reason to be cautious. In 2014, AFP photojournalist Hector Guerrero had a troubling experience while visiting the graveyard with another foreign news organization. They had been in the cemetery for no more than 15 minutes when a man walked up to them with a radio in his hand.

The man told the crew: "What are you doing? It's better that you leave because I was told on the radio that they will abduct you."

They packed their gear but as they drove away, armed men showed up in sport-utility vehicles. They may have been police officers, but Hector was not sure. In any case, seeing local police in Mexico isn't always reassuring because they are often on the payroll of drug cartels. The armed men asked the journalists to get out of their car. After Hector's fixer explained that he had a relative buried there, the gunmen told the journalists: "Leave. You can't be here."

(AFP / Alfredo Estrella)

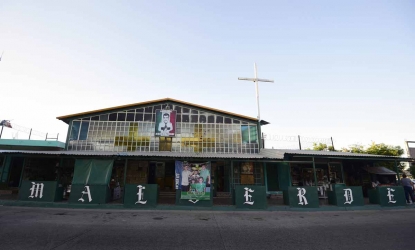

(AFP / Alfredo Estrella)After we left the cemetery, we went to a chapel dedicated to folk saint Jesus Malverde, a mustachioed bandit who, according to legend, stole from the rich and gave to the poor until he was hanged in Culiacan in 1909.

The green building (in Spanish “Malverde” means "Bad Green") features a dark prayer room where believers can kneel before a bust of Malverde to plead for miracles.

(AFP / Alfredo Estrella)

(AFP / Alfredo Estrella)Contrary to what many may think, criminals are not his only followers. We saw a cab driver and a flower seller during our weekday visit. The place can be packed with visitors during weekends. There's no way they can all be cartel footsoldiers.

The walls of the chapel were filled with US dollar bills as well as currencies from other countries. Others whose prayers were answered pay him back by hiring musicians to perform at the chapel, lighting candles or placing tiles with thank you messages.

Faith in folk saints such as Malverde and Santa Muerte, the Death Saint, are part of an explosion of the "narcocultura," or narco-culture, that has grown during the decade-old drug war. The phenomenon includes folk bands singing the praises of drug lords and television channels producing soap operas inspired by the men and women of the criminal underworld.

Feeling that our story was lacking context, I contacted a local expert, Juan Carlos Ayala, a philosophy professor at the Autonomous University of Sinaloa who specializes in narcocultura.

Ayala suggested that a good place to speak for our video report would be ... the cemetery. Eager to get more images and details about the place, we returned even though we were getting close to sunset (it's not advisable to be out at night in narco land). Ayala, through his research, is able to get access there, so we felt safe enough to roam around the place with him.

Juan Carlos Ayala speaks at the Jardines del Humaya cemetery, December, 2017.

(AFP / Alfredo Estrella)

Juan Carlos Ayala speaks at the Jardines del Humaya cemetery, December, 2017.

(AFP / Alfredo Estrella)Some tombs had surveillance cameras trained at their entrance and signs indicating they had alarm systems. At least one had bulletproof glass. By squinting, I could peek through the glass and see four small swords inside a crystal case. Other crypts had air conditioners and were decorated with Christmas trees.

Ayala voiced concern that Mexico was heading toward a "culturization of drug trafficking," but he said the acceptance of narcocultura was a sort of "protective layer" for people to deal with the violence. "Otherwise imagine living with anxiety all the time, with each massacre, with each crime. ... It's very hard to live like this. So you have to survive with this, and this protective layer helps in a way."

As we interviewed him, night fell and luxury SUVs arrived at the cemetery. Young men and women were going into some crypts. We decided it was best to head back to the modest rooms at our hotel -- sans bulletproof glass.

This is what I often have to explain to people outside Mexico. Unlike a conventional war, the threats are often subtle or invisible. In some regions, you never know if the civilian or cop you're talking to is working for a cartel. Is it sometimes paranoia? Doesn't matter. The story is never worth the risk.

(AFP / Alfredo Estrella)

(AFP / Alfredo Estrella)After visiting the Pharaonic burial grounds, the drug trade’s end of the line, we headed to the starting point -- the Sinaloa drug cartel empire's fertile grounds, where farmers grow marijuana and an increasing amount of opium poppy fields.

The army had accepted our request to follow their drug eradication program in the Golden Triangle -- a mountain region straddling the states of Sinaloa, Durango and Chihuahua that has produced marijuana and opium poppies for decades.

A Mexico poppy in the state of Guerrero, January, 2016. (AFP / Pedro Pardo)

A Mexico poppy in the state of Guerrero, January, 2016. (AFP / Pedro Pardo)After a short night's sleep, we drove from Culiacan to the town of Badiraguato, the fiefdom of some of Mexico's most notorious drug kingpins, including Guzman and his top associate, Ismael "El Mayo" Zambada, who is believed to have taken over the Sinaloa cartel's leadership since Chapo's capture in January.

After more than four years in Mexico, it was the first time that the army or navy had accepted one of my requests to follow a drug-related operation. Their opaqueness has always been frustrating. The armed forces are on the frontlines of the drug war, risking their lives, but they have also committed grave human rights violations doing the work that experts say only police should be doing. In my requests, I always argued that I wanted to be able to tell their side of the story. Until now, the argument had not convinced them.

Mexican soldiers burn a field of poppies in Sinaloa state, December, 2016.

(AFP / Alfredo Estrella)

Mexican soldiers burn a field of poppies in Sinaloa state, December, 2016.

(AFP / Alfredo Estrella)We were met by Colonel Cipriano Cruz Quiroz, chief of the special unit in Badiraguato, who gave us a presentation before we hopped on a military pick-up truck and headed up the winding roads of the Sierra Madre Occidental mountain range at 8:05 am. We drove past Los Sitios, a small village where we spotted at least two large homes with high walls and barbed wire, a sign of wealth in a region that didn't seem to produce much corn or beans. At around 9:30, we arrived at another army base in Surutato. We picked up more soldiers and headed up a rocky dirt road for another 45 minutes. The road ended and the real challenge began.

(AFP / Alfredo Estrella)

(AFP / Alfredo Estrella)We began our trek at around 10:30, trying to keep pace with well-trained soldiers walking on a narrow path along a steep hill, then up wider but slippery terrain. The higher we got, the harder the climb with less oxygen. Almost three hours later, we reached a tent camp that was home to a unit of 18 soldiers led by a 24-year-old Lieutenant Juan Pablo Hernandez Zempoaltecatl. Such units live in the mountain for three months at a time, looking for marijuana and opium poppy fields that they destroy by hand when fumigation flights are not available.

We watched them destroy a 0.5-hectare (1.2-acre) opium poppy field in less than two hours. They had destroyed 15 hectares in that part of the mountain in two weeks. But Hernandez pointed up and down the mountain. More fields. Everywhere, hidden behind pine trees. They were looking at 20 more days of ripping poppies by hand, knowing that the farmers would come back once they were gone to plant again. Colonel Cruz said it was simply part of the local "subculture" in a region where growing drugs has been passed on from generation to generation.

Was this back-breaking effort useless? I asked Hernandez bluntly. "It's tiresome to see so many poppies every day," he said as we walked back to his camp.

Poppies galore. Sinaloa state, December, 2016. (AFP / Alfredo Estrella)

Poppies galore. Sinaloa state, December, 2016. (AFP / Alfredo Estrella)But, he said, children who see the army up there may turn away from the drug business and decide to focus on school and getting a regular job.

(AFP / Alfredo Estrella)

(AFP / Alfredo Estrella)As I walked back down the mountain -- with both my knees needing ice like an aging soccer player after a game -- Colonel Cruz asked me if we thought that going up there was dangerous. The soldiers told me they had never been attacked by gunmen. The farmers radio each other to report troop movements and usually disappear when eradication teams arrive. Five soldiers were killed in September when a convoy carrying a wounded cartel suspect was attacked by dozens of gunmen in Culiacan. But that was in the city. Cruz suggested that it was safer up in the hills.

And I have to admit that somehow, up in the mountains where the seeds are planted for a multi-billion-dollar drug business that kills thousands of people each year, be they addicts in the US or participants and bystanders in the drug war in Mexico, I felt a bit safer than in a cemetery full of dead drug lords.

(AFP / Alfredo Estrella)

(AFP / Alfredo Estrella)