The terrible beauty of a Mexican mass grave

IGUALA DE LA INDEPENDENCIA, Mexico, Nov. 4, 2014 - As night falls over the slopes of the Cerro Gordo, the kaleidoscope of colours from yellow to black should be a delight for a photographer like myself. But the stunning natural beauty of the site in southern Mexico conceals a horrific hidden truth. The majestic mountain is a mass grave, a dumping ground for dozens -- if not hundreds -- of people fallen victim to the hellish violence of the Mexican drug trade.

In the centre of Iguala de la Independencia, the church of San Francisco, its belltower adorned with pretty blue ceramics, is a silent witness each day to the comings and goings of a sinister army.

The "Halcones" -- or Falcons -- as they are dubbed in Mexico are the low-level informants paid to spy on local goings on, and report back to the drug cartel bosses hidden deep in the mountains.

Mexican Marines patrol the mountains around Iguala on October 1st, 2014 (AFP Photo / Yuri Cortez)

For days the town of 140,000 people has been full of journalists, and the snitches have gone into overdrive.

The crime bosses want to know everything: who we talk to, where we sleep. So their spies are everywhere, their scooters revving up to speed off behind each car marked "press".

Dodgy-looking characters lurk outside -- and inside -- hotels, waiting for a chance to snap a not-so-discreet picture or fire off a text message.

Police and traffickers hand-in-hand

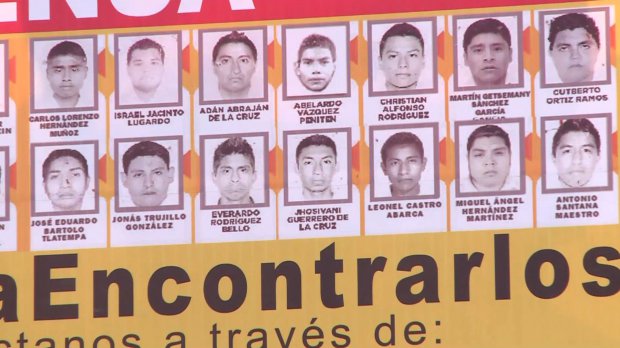

We are here because of what happened the night of September 26, when Iguala local police and members of the Guerreros Unidos drug cartel attacked several student buses. Six people died and 43 trainee teachers vanished into thin air.

Despite some 2,000 rescuers combing the area the fate of the students remains unknown -- but the search has uncovered scores of bodies, dumped in unmarked graves, laying bare the extent of gang crime in the region.

Vultures fly over the Cerro Gordo on October 10, 2014 (AFP Photo / Yuri Cortez)

Vultures fly over the Cerro Gordo on October 10, 2014 (AFP Photo / Yuri Cortez)Dozens of people have been arrested, including the suspected head of the Guerreros Unidos, as the shocking case exposed an unprecedented level of complicity between the town mayor and his wife, local police and drug gangs.

In the sky above the Cerro Gordo, the Latin American vultures known as urubu circle endlessly overhead. A young villager tells us what it is like to live at the foot of the mountains, in territory he says is under the absolute control of the drug cartels.

"Every day after 10 pm, you can see their vans coming and going. We all know these are bad people, so we don't set foot outside our homes.

Click here to view this video from a mobile device.

"We are afraid. Afraid for ourselves and afraid for our children. I often tell my wife, the day I see these guys coming towards our house I will kill at least two of them."

"There are a lot of mass graves around here, but no one will talk about them. Everyone is terrified," said the young farmer.

From time to time, he says, one of his Catholic neighbours has planted a cross above these nameless graves. But apart from telltale mounds of freshly dug earth -- there is no way of locating the graves.

On October 4, the search uncovered a grave with 28 bodies. None of the students were among the bodies pulled from the ground.

Victims screams, torturers' laughter

So who are the dead?

For want of tombstones or candles, the Cerro Gordo honours them in its own, poignant way with the thousands of wildflowers that light up its slopes in a glowing palette of yellow, orange and crimson.

As darkness settles over the landscape, journalists start heading back for the night. Some plan to sleep in the state capital Chilpancingo, feeling unsafe in the hotels of Iguala, where the cartels' lookouts hover. Others decide to risk a night in town.

One of the mass graves discovered near Iguala on October 6, 2014 (AFP Photo / Pedro Pardo)

One of the mass graves discovered near Iguala on October 6, 2014 (AFP Photo / Pedro Pardo)Our team chooses to stay close to the search, in an outpost set up by the authorities, counting on the presence of elite federal police units, and pick-up trucks mounted with machine guns and rocket launchers to keep danger at bay.

That night I get chatting with a police commander who could have been lifted straight from an episode of the 1980s series "Miami Vice".

He tells me the newly-found mass graves were discovered thanks to intelligence work by his men, showing off a picture of clothing fragments on his mobile phone -- but declining to hand over the picture.

Wild flowers cover the landscape near Iguala (AFP Photo / Yuri Cortez)

Wild flowers cover the landscape near Iguala (AFP Photo / Yuri Cortez)The Cerro Gordo's infamous status as a gigantic mass grave is so ingrained by now that the taxivan that links up the villagaes at the foot of the mountain has been renamed "la combi del cementerio" (the cemetary van).

"At night you can hear screams of pain, it's appalling, as if people were being tortured," a deep-tanned villager tells me as he harvests crickets -- grilled and eaten as a snack in this part of the world.

His wife nods in agreement. After the victims' screams, she says, you can often hear the torturers laughing.

Blankets soaked in blood

Dawn breaks to reveal the terrible beauty of the site, its multicoloured flowers and lush tropical foliage like a stubborn tribute from mother nature to the unnamed victims beneath the ground.

With no road leading into the Cerro Gordo the police, firefighters and miltary working the case have had to cut a path through the wilderness to gain access. But that road is off limits to the press.

We set out to explore the area, first by car then on foot, traipsing for hours under a beating sun in an air heavy with humidity after a rainy night.

We walk through pastures and vegetable plots buzzing with insects that swarm around us -- keen to tuck into the feast offered by a rare human apparition.

Following the leads given to us by locals and fellow journalists we find what we are looking for.

Marines and forensic personnel head for the place where a mass grave was found in Iguala on October 10, 2014

(AFP Photo / Yuri Cortez)

The sense of suffering and death is overpowering as we cross scraps of clothing, shoes in adult and child sizes emerging from the ground, sometimes charred.

There are traditional Mexican boots, blankets soaked in coagulated blood. In many places the earth shows signs of recent digging.

We are without a doubt in the middle of a giant graveyard, where nature in all its glory is fed with human blood.

Urubu vultures circle overhead, drawn by the strench of death. Their shrieks, and the humming of flies, are the only things to break the thick silence.

We realise with horror that if we started digging, anywhere, at random, we might find human remains.

The local language nahuatl has a word -- "Iguala" -- which means "where the night settles down". For the poor souls who rest beneath our feet, the night will be an eternal one.

Yuri Cortez is an AFP photographer based in Mexico. He was part of a multimedia team that travelled to Guerrero State in October 2014.

Relatives and friends of the 43 missing students take part in a mass in Chilpancingo on October 14, 2014

(AFP Photo / Yuri Cortez)