Suarez, Uruguay's raging hero

MONTEVIDEO, July 11, 2014 - I'm a journalist. From Uruguay.

Those were two separate biographical details, until The Bite. As a reporter, I tried to stick to the facts when Luis Suarez was expelled from the World Cup for biting Italian defender Giorgio Chiellini.

As a Uruguayan, it was deeply painful to see our team lose its talisman, the explosive striker who had battled back from knee surgery to restore a glimmer of our little country's faded football glory.

It made me think of Shakespeare's "Richard III": "Madam, have comfort: all of us have cause to wail the dimming of our shining star; but none can cure their harms by wailing them."

There's not much comfort to be found. The only source - for me anyway - is to try to understand what happened.

Luis Suarez and Giorgio Chiellini after the bite (AFP Photo / Daniel Garcia)

Luis Suarez and Giorgio Chiellini after the bite (AFP Photo / Daniel Garcia)Being Luis Suarez

"Take that!" Suarez had said, fighting back tears, after pushing England to the brink of elimination with two crack goals in their World Cup clash on June 19.

Uruguay's victory had all the ingredients of an epic: tragedy, tension and a thrilling ending in the form of a 2-1 win heralding Suarez's return from surgery less than one month before.

After watching our team lose 3-1 to Costa Rica playing without Suarez in our opening match, Uruguayans surrendered our hearts to our star.

We elevated him to the status of favorite son, of king. We venerated and adored him. He had fulfilled his promise to return, and then some.

"I'm enjoying this moment after everything I suffered, after all the criticism I received," said Suarez, the Premier League's leading scorer last season with 31 goals.

Luis Suarez bites Chelsea defender Branislav Ivanovic in April 2014 (AFP Photo / Andrew Yates)

Luis Suarez bites Chelsea defender Branislav Ivanovic in April 2014 (AFP Photo / Andrew Yates)The message, tinged with vengeance, had a clear target: an England that knows the Liverpool forward all too well, where many see him as a thug who racially abused Manchester United's Patrice Evra and bit Chelsea's Branislav Ivanovic.

England coach Roy Hodgson had raised the stakes before the match when he said Suarez had "potential" but still had to prove himself on the World Cup stage to join the ranks of Diego Maradona, Pele, Franz Beckenbauer, Johan Cruyff and Andrea Pirlo.

The striker answered with a double praised around the world, fueling talk of a transfer to Barcelona.

"I have to say that Suarez is a phenomenon. His performance challenged the limits of the imagination," said former England star Gary Lineker, now a sports commentator.

The British press was more mordant, ambivalently praising Suarez's "killer" performance.

"He is utterly relentless on the pitch, with a nastiness that gives him an insatiable hunger," wrote The Times. It was as if they had seen the future.

The fall

A week later, the 27-year-old returned home like a pariah, expelled from the World Cup. FIFA's Disciplinary Committee suspended him for nine matches and banned him from all football-related activities for four months for biting Chiellini's shoulder. To Uruguayans, the punishment was an attack on our country.

FIFA kicked him out of not just the World Cup but also a good portion of Uruguay's title defense at the 2015 Copa America, South America's continental championship.

It was too much to bear.

Many Uruguayans overlooked the fact that this was the third time Suarez had been punished for biting an opponent.

We forgot, denied or minimized his prior convictions -- a seven-match suspension in 2010 for biting PSV Eindhoven's Otman Bakkal when playing for Dutch side Ajax, and 10 matches last year for biting Ivanovic.

"Such behavior cannot be tolerated on any football pitch, and in particular not at a FIFA World Cup when the eyes of millions of people are on the stars on the field," said FIFA Disciplinary Committee chief Claudio Sulser.

The suspension, which came as Uruguay prepared to face Colombia in the round of 16, was the harshest ever imposed for an incident between players at the World Cup.

"If it's the first time it's an incident. If it is more than once it is not an incident. That is why the ban was exemplary," said FIFA secretary general Jerome Valcke.

Hothead with heart

Like all Uruguayans, I wanted to believe the bite never happened. I told myself it was probably just shoving. Suarez often has his mouth open, and he's got those enormous teeth.

I remembered his grandmother Lila Piriz da Rosa, who still lives in the northwestern city of Salto, Suarez's hometown. It wasn't hard to find her. At first she said she didn't want to talk. "I already said everything I had to say," she told me.

But five minutes later we were chatting like old friends.

"I don't know what's going on with my 'negrito,'" Piriz said -- a diminutive nickname that is, ironically, the same word Suarez used for Evra in the incident that led to his racism ban.

"I don't know why he has these explosive outbursts. He can't control them, even though he has everything he needs to be happy," said the octogenarian, who has 22 grandchildren and 23 great-grandchildren.

A Uruguayan woman sings the national anthem in Montevideo as Uruguay-Colombia match is broadcast live, June 28, 2014. (AFP Photo / Miguel Rojo)

A Uruguayan woman sings the national anthem in Montevideo as Uruguay-Colombia match is broadcast live, June 28, 2014. (AFP Photo / Miguel Rojo)Suarez rose to worldwide fame for his "Hand of God" at the 2010 World Cup, when he stopped a certain winning goal by Ghana in the quarter finals with his hand. e was sent off for the infraction, but Uruguay went on to win in a penalty shootout, reaching the semi-finals. Uruguayans celebrated his "sacrifice," which put us back in the ranks of World Cup contenders after decades of disappointment.

"He's not a hero, he's a trivial cheat. What hand of God? It was the hand of the devil," said Ghana's then coach Milovan Rajevac.

The infamous handball from Suarez that deprived Ghana of a quarter-final win at the 2010 World Cup in South Africa in 2010. (AFP Photo / Yasuyoshi Chiba)

The infamous handball from Suarez that deprived Ghana of a quarter-final win at the 2010 World Cup in South Africa in 2010. (AFP Photo / Yasuyoshi Chiba)Suarez was known for badgering his opponents even as a boy. Street football in Salto was no-holds-barred, said his grandmother.

"He had a lot of outbursts. He was wild," she said, laughing. Then she grew serious.

"Maybe it's his parents' divorce, the hardships they went through," she said. "They were a young couple that moved to Montevideo with six kids."

Rodolfo Suarez, a soldier and local footballer, and Sandra Ruiz moved their family from Salto to the Uruguayan capital when Luis, the fourth of seven brothers, was seven years old. Suarez had trouble adapting, according to journalist Ana Laura Lissardy's book "Vamos que vamos," a collection of interviews with the Uruguay national team. Two years later his parents split up. The children stayed with their mother, a cleaner.

"His parents' separation shook the ground beneath his feet," Lissardy wrote.

He was not an easy child or teenager, and even his interest in football was mercurial.

"We did not have many resources at home, which meant we had to carry on with a very normal life, full of sacrifices," says his official website. "I started playing football when I was very young and by the age of four I would run faster with the ball than without it. But it wasn't until I was 14 that I started playing football seriously when I was selected by Nacional de Montevideo."

That same year his life changed when he met the girl who would become his wife, Sofia Balbi, one of his main inspirations to pursue professional football.

She became a guiding force that helped control "both my life and my head," he told ESPN Brazil last November. But the sweethearts were forced apart when Balbi moved to Barcelona with her parents. Suarez decided the only way to get her back was to become a professional footballer.

No sooner had he signed his first European contract with Dutch club Groningen in 2006 than he asked Balbi's parents to let their then-16-year-old daughter move with him to the Netherlands.

But despite his meteoric rise, the rage was always there.

From Groningen he was traded to Ajax, one of Europe's most prestigious teams. But soon after his arrival he was suspended over an altercation with a teammate.

Uruguay coach Oscar Tabarez summed up Suarez's volatile character at the start of the World Cup.

Suarez scores for Liverpool in Mansfield Town, January 2013. (AFP Photo / Andrew Yates)

Suarez scores for Liverpool in Mansfield Town, January 2013. (AFP Photo / Andrew Yates)"He's the first to get (to practice) and he's going to do what he always does: get mad during scrimmages, criticize (Jose) Herrera, who's the referee, complain that he's out to get him and that sort of thing, and spend the next few hours in a bad mood whenever he loses," he said.

Family members say he takes after his dad.

"His father's a hothead. A good person but with outbursts, too. The worst personality of my six children," said Piriz.

"Luisito inherited it. We never thought Luisito was going to be the most famous of the bunch with that personality of his."

Suarez himself says his explosive personality is at the heart of his success.

"You can lose some things, but can never lose the slyness, the passion that you have had since you were a kid playing in the street," he told AFP in a March 2013 interview.

"If I didn't have the character that I have today on the pitch, I don't think that I would have become the player that I am."

I ask myself if that can be true.

Is it true that Michaelangelo was the greatest, most revolutionary Renaissance artist precisely because of his egotistical, obstinate, violent temper? Frank de Boer, who coached Suarez at Ajax, says the player "needs psychological help."

"When he sees he can't win or that something is resisting him, sometimes he reacts like that," he told Dutch newspaper Algemeen Dagblad.

Sports psychologist Pablo Martinez of Uruguay's University of the Republic said biting others generally "appears in people who have had a very aggressive, very poor childhood, and is a form of self-defense against external aggression or adults."

"He has been treated by a psychologist for anger management and I thought he had it under control," Martinez told AFP.

"But something happened at the World Cup, something that made that more primitive instinct emerge."

I've always believed it must be complicated for these young Latin American footballers who go from lives of extreme poverty to stardom and riches almost overnight.

Latin America is a mine for promising talent. But statistics show that just 0.1 percent of children make it as footballers.

"The kids that triumph have survived thousands of things, far from their families, with the responsibility to be the family breadwinners. They're not kids, they're workers," said Juan Pablo Meneses in his book "Ninos futbolistas" (Footballer Kids).

We are all Suarez

Uruguayans could talk of nothing else. At barber shops, bars, hospitals, offices and online, the visceral anti-FIFA reactions flowed. Even President Jose Mujica joined the fray.

"FIFA are a gang of old sons of bitches," he said.

Politicians of all stripes backed him up on social networks, which were inundated with hashtags like #FifaMafia and #TodosSomosSuarez (We are all Suarez). There were calls for protests, for Uruguay to withdraw from the World Cup.

Some said it was all a FIFA plot to distract the media from the corruption scandals engulfing the world football governing body, particularly around the awarding of the 2022 World Cup to Qatar.

Uruguayan president Jose Mujica. (AFP Photo / Claudio Reyes)

Uruguayan president Jose Mujica. (AFP Photo / Claudio Reyes)Other conspiracy theorists said it was a Brazilian scheme to eliminate Uruguay, the team that humiliated them in the final match the last time they hosted the World Cup, in 1950.

Still others blamed the British press for persecuting Suarez. After all, it was just a bite, wasn't it?

We recalled the brutal aggression shown by France's Zinedine Zidane when he headbutted Italy's Marco Materazzi in the 2006 World Cup final. He was suspended for just three matches.

And what about Brazilian Leonardo, who broke American Tab Ramos' nose at the 1994 World Cup? He was suspended for just four games.

Zinedine Zidane's infamous headbutt on Marco Materazzi during the 2008 World Cup final. (AFP Photo / John MacDougall)

Zinedine Zidane's infamous headbutt on Marco Materazzi during the 2008 World Cup final. (AFP Photo / John MacDougall)Mujica said their was a campaign against Suarez.

"They can't forgive him his flaws," he said.

"They've got something against him, because there's always a camera following him," said Roberto Mezza, a friend of Suarez's father.

"Also, I always say that in football you play full throttle. You have to absorb a thousand things, if they hit you, if they talk trash at you. Sometimes there comes a moment when they wear you down. And knowing how he is, that he's got a temper, they provoke him."

Those of us hoping there had been no bite got a dagger in the heart.

The incident happened during the second half of the match, which Uruguay ended up winning 1-0 to reach the round of 16 and send the Italians packing.

Suarez and Chiellini had been battling for position near the Italian goal when the striker bit the defender, getting an elbow in return.

Both fell to the ground in what looked, at first, like a typical clash between two physical footballers who like to play rough.

But TV images showed what the referee, Mexico's Marco Rodriguez, missed: Suarez chomping into Chiellini's left shoulder.

Many Uruguayans, however, are still convinced the video was doctored.

An exception is aging national hero Alcides Ghiggia, who scored Uruguay's World Cup-winning goal against Brazil in 1950.

"This boy's clearly not right in the head. That's just not something you do on the pitch," he said.

It's not easy to say it. You risk being called a traitor.

The "Maracanazo": Uruguayan forward Juan Alberto Schiaffino scores the equaliser against Bazil during the 1950 World Cup final in the stadium at Maracana de Rio. Against all predictions, Uruguay won 2-1, becoming champions for the second time. (AFP)

The "Maracanazo": Uruguayan forward Juan Alberto Schiaffino scores the equaliser against Bazil during the 1950 World Cup final in the stadium at Maracana de Rio. Against all predictions, Uruguay won 2-1, becoming champions for the second time. (AFP)In Uruguay, a secular country, football is our religion. And you must love God unconditionally. You don't try to understand Him.

Sandwiched between continental giants Argentina and Brazil, this little nation born as a buffer state in the early 19th century has forged its identity and its famed "garra charrua" (Uruguayan guts) on the football pitch.

We have just three million people, but we've won the World Cup twice, in 1930 and 1950. We've won the Copa America 15 times.

That makes us the country with the most glory per capita in the world.

What's worse, breaking someone's nose, biting or giving a headbutt? Football is a sport. It has its rules.

Without a doubt, Uruguay lost. Not just in its 2-0 defeat to Colombia in the round of 16. Suarez apologized five days after the fact. But I would like him to explain what happened.

"I deeply regret what occurred," he said in a statement posted online.

"I apologize to Giorgio Chiellini and the entire football family. I vow to the public there will never again be another incident like (it)."

It was too late for many, especially when it was reported that Barcelona were in the middle of negotiations with Liverpool to acquire the striker. Some speculated the apology had been part of the millionaire deal.

Uruguayan fans demonstrate in support of Suarez in front of the team hotel in Natal, June 26. (AFP Photo/ Daniel Garcia)

Uruguayan fans demonstrate in support of Suarez in front of the team hotel in Natal, June 26. (AFP Photo/ Daniel Garcia)Since The Bite, there has been a flood of memes on Twitter: Suarez with a conical dog collar, Suarez as Hannibal Lecter.

In one of the most recent of the 57,726 comments beneath a family photo on Suarez's Facebook page, Anonymous wrote: "Family of biters." It won't be easy for him to battle back from this one.

"I have a very strange way of playing football," Suarez told AFP last year.

But "I'm my own severest critic and I realize when I make mistakes," he added.

No, Suarez is no God. But he's also not a cannibal or a rabid dog or a vermin.

Maria Lorente is AFP's editor-in-chief for Latin America.

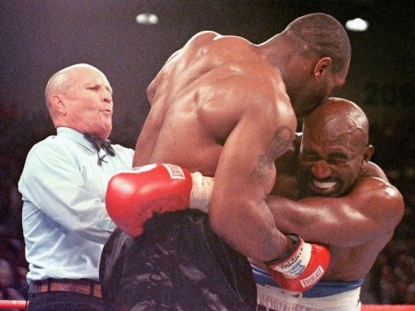

Another infamous bite: Mike Tyson chews off part of Evander Holyfield's ear during a heavyweight championship fightin Las Vegas, June 26, 1997. (AFP Photo / Jeff Haynes)

Another infamous bite: Mike Tyson chews off part of Evander Holyfield's ear during a heavyweight championship fightin Las Vegas, June 26, 1997. (AFP Photo / Jeff Haynes)