Buried past comes back to haunt France

A series of investigations by AFP journalist Lucie Peytermann has forced the French government to face up to a shameful betrayal of those who fought for France during the war in Algeria

The text message landed like a meteorite. “Hi Lucie. We have found it!” I was in the newsroom and my heart jumped. The graves of babies and children who died in appalling conditions in a camp run by the French military in the early 1960s had been found on waste ground on army land in the south of France.

Their fathers were Harkis – Algerian Muslims who fought for France during the long and bitter war there – and who faced terrible reprisals and massacres at independence in 1962. Some 90,000 men, women and children fled for their lives across the Mediterranean to France only to find themselves corralled into grim camps, where child mortality was shockingly high.

The cemetery was by one such Harki camp north of Avignon, its existence hidden from the families of the dead children for decades. My feelings swung between joy and relief and the pain I knew the news would bring to the families who have been trying all these years to find the graves. Their story is another twist in one of the most shameful episodes in modern French history.

Archaeologists found the child cemetery close to the former Harki camp at Saint Maurice in March (AFP / Pascal Guyot)

Archaeologists found the child cemetery close to the former Harki camp at Saint Maurice in March (AFP / Pascal Guyot)

Before the Harkis were brought there in October 1962, Saint Maurice l'Ardoise had been a prison camp for their adversaries, suspected FLN members fighting to free Algeria from French rule, and then for French OAS extremists who refused to accept Algeria’s independence, and who repeatedly tried to kill President Charles de Gaulle.

The isolated camp had been built to hold 400 people. But 5,000 Harkis and their families would endure two of the coldest winters of the century there in tents. Many were still living behind its barbed wire fences 15 years later.

Abandoned and forgotten, its child cemetery was rediscovered last month after an unprecedented dig ordered by the French state. Two archaeologists from France’s INRAP institute confirmed on March 23 that they had found about a dozen babies and children buried in unmarked graves in fields and waste ground near the camp. “It’s the cemetery we have been looking for,” said one of them, Patrice Georges-Zimmermann.

The discovery was the climax of the three years I have spent trying to cast light on this state scandal, and the tragedies behind it, with the help of some remarkable historians and the unswerving efforts of local Harki groups. From the start it has been a race against time, with fewer and fewer witnesses still alive.

I wrote the first article revealing the existence of the cemetery in September 2020 after eight months of investigation. Then, for several months, I was told it would be impossible to find the remains after all this time, particularly since they were children’s bones. But the Harki groups refused to give up and I continued to grill the ministry.

Then at the start of last year the minister of state for veterans’ affairs finally ordered a search. The first dig that winter turned up nothing. But Georges-Zimmermann was convinced they were close, and he was right. A new dig a few hundred metres away led to the finds in March.

Malika Tabti (left) and Nadia Ghouafria, whose efforts were key to the discovery of the burial site, at the spot near the Saint Maurice camp where Malika's baby sister was buried in 1963 (AFP / Nicolas TUCAT)

Malika Tabti (left) and Nadia Ghouafria, whose efforts were key to the discovery of the burial site, at the spot near the Saint Maurice camp where Malika's baby sister was buried in 1963 (AFP / Nicolas TUCAT)

A fortnight after the announcement, I went to the spot with Malika Tabti, whose baby sister was buried there after dying seemingly from measles in 1963. The family had tried in vain for years to locate her grave. Malika only learned of the existence of the cemetery – a patch of ground straddling a country road marked with a sign saying “Military zone” – from one of my articles.

Tears running down her face, she left flowers at the spot now marked out with wooden posts where 31 people, 30 of them babies and small children, were buried. We had been in contact for over a year, and to see this dynamic, professional 59-year-old woman so wracked with pain, shook me. I too had tears in my eyes. Often during the investigation, I felt the burden of plunging the families back into the traumas they had been through.

For three years I have crossed and re-crossed southern France doing hundreds of hours of often deeply poignant interviews with relatives and witnesses and been helped by historians like Abderahmen Moumen and Fatima Besnaci-Lancou. I have accumulated piles of notebooks, and spent days and days collating information from families scattered across France. There have been sleepless nights, the weight of having to keep certain information confidential, and of having to choose my words very carefully. Even six decades after the Algerian war of independence, this is still a deeply sensitive subject in France.

Harkis and their families arriving at the Rivesaltes camp in September 1962 just after Algerian independence (AFP)

Harkis and their families arriving at the Rivesaltes camp in September 1962 just after Algerian independence (AFP)

The Harkis may have been French citizens but they were abandoned and largely left to their fate when the vicious eight-year war in Algeria ended in 1962, despite having fought with the French army as auxiliaries.

The 90,000 men and their families who made it to France were put into notorious “transit and processing camps” run by the French army in Saint Maurice and other often remote and windswept places like Rivesaltes and Larzac.

Eventually many were resettled elsewhere in France, but Saint Maurice and Bias in the Lot became semi-permanent “estates for those repatriated from Algeria”. They only closed in December 1976 after the residents revolted, with the young in particular protesting the “penitential nature” of the camps with their barbed wire and curfews.

Life was extremely harsh in the camps and infant mortality rates were high, with measles outbreaks claiming many young lives. Mothers were also having to give birth in shocking conditions and many – already ill or weakened from what they had suffered in Algeria – had miscarriages.

Scores of the newborns or very young children who died were hastily buried by their families or the soldiers guarding them within the camps or nearby, according to historians. There was rarely a grave marker worthy of the name. Soon the graves disappeared under long grass or brambles or were even covered by vineyards. Families of the dead children who had been rehoused far away tried to rebuild their lives, burying the ghosts of their trauma deep within themselves.

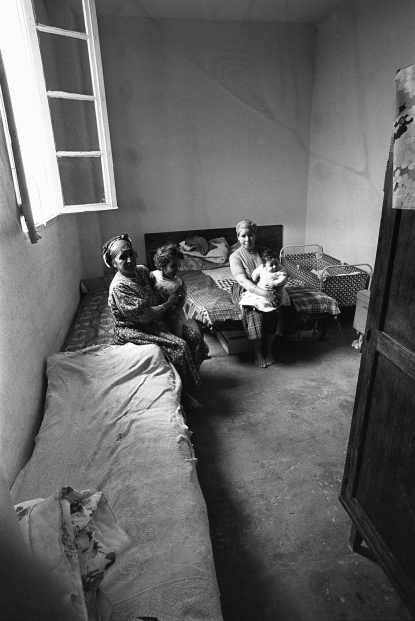

Harki women and babies in the single room where they lived with their family in the Saint Maurice camp in June 1975

(AFP )

Harki women and babies in the single room where they lived with their family in the Saint Maurice camp in June 1975

(AFP )

Even 60 years after the war, the prejudice and condescension that the Harkis still suffer shocked me and pushed me to dig deeper. If France is ever to heal the wounds of those awful years, we have to acknowledge the hell the Harkis went through after their arrival in France and the tragedy that was allowed to befall their children.

As a French woman, I felt their story was also mine. In documenting the injustice they suffered, I realised that it was above all the men – the surviving Harki fighters and their sons who have taken on the mantle – who spoke for the community. But you almost never hear the voices of Harki wives or daughters. Silence hung over what they had endured.

In the winter of 2020, I came across the staggering work of historian Abderahmen Moumen. In 2015 he had been asked by the French national office for veterans and the victims of war to find a cemetery at the vast, notorious former Harki camp at Rivesaltes near Perpignan. By 2017 he had been able to work out where it was. A commemorative pillar was later erected but no dig was ordered.

However, from data he had managed to gather, I was able to publish stories in 2020 revealing that not only were the majority of the 146 who had died at Rivesaltes children, 101 were less than a year old.

My interest in Saint Maurice – which I also investigated for eight months in 2020 – was piqued after government officials advised me not to “get too interested” in it. I got in contact with local Harki groups and in particular with Nadia Ghouafria, whose parents had lived in the Lascours and Saint Maurice camps.

She had discovered a dossier of files in the local archives about a cemetery, which included a statement from a police officer in 1979 showing that the local authorities not only knew about the cemetery, but deliberately did not inform Harki families.

The scandal within the scandal was that nine of the 30 children buried there had been exhumed in 1979 – but to the horror and disbelief of the families, no one seems to know what was done with the remains.

The trauma of all that the Harkis have been through has poured down the generations, as my AFP video reporter colleagues Guillaume Bonnet and Ysis Percq, who have worked with me, can testify.

The Dargaid family, (from left) Rahma, Abdelkader and Abessia, at the grave of their twin brothers who died in 1962

(AFP / Lionel BONAVENTURE)

The Dargaid family, (from left) Rahma, Abdelkader and Abessia, at the grave of their twin brothers who died in 1962

(AFP / Lionel BONAVENTURE)

Like Malika Tabti, the Dargaid family could not hold back their tears when they finally found the last resting place of their twin brothers, who died just after their birth in the Rivesaltes camp’s infirmary. Apart from two little bumps on a bare patch of earth in the Muslim section of Perpignan cemetery, there is nothing to indicate the two boys lie there.

Harki activist Hacene Arfi was one of the first to speak out about the scandal. He told me how aged six in November 1962 he watched his father dig a grave for his stillborn brother with his bare hands in the vast, bare Rivesaltes camp. Riven by trauma and grief, his father still can’t remember exactly where it was.

However, our reporting pricked the conscience of government and has now forced it to act. Former veterans’ minister Genevieve Darrieussecq admitted it was “morally not normal” that the families were not told about the Saint Maurice graveyard in 1979, saying “the Republic was at fault”.

Her successor Patricia Miralles visited the site last week, saying that “we have to recognise and right the harm” that was done. She said the French state would build “a burial place worthy of this painful memory”. Those families who wish will also be able to bury the bones elsewhere. Which is what Malika Tabti wants, hoping that her sister can “finally rest in peace” next to her mother, who died in 2018.

The cemeteries are now an issue that won’t go away. More families who have been looking for the graves of their brothers and sisters for years have contacted me over the last month. And with them come some painful questions for the French government.

The discovery of the Saint Maurice graves has given some families finally the chance to grieve properly. But it is also the beginning of a new struggle for a dignified memorials for all of the Harki children.

Edited by Fiachra Gibbons and Catherine Triomphe