AFP in the time of coronavirus

It was the arresting image of an elderly man in a face mask lying dead on a pavement in Wuhan which told us that perhaps it would be different this time. It was January 30 and AFP journalists had been covering the increasingly dystopian scenes in the Chinese megapolis. Now it suddenly felt out of control, bigger than we imagined. AFP clients seemed to feel it as well. The picture taken by Hector Retamal of the anonymous corpse surrounded by faceless and hesitant officials in protective white suits struck a chord with the global media. "The Image That Captures The Wuhan crisis," headlined The Guardian. It felt like a warning.

This photo taken on January 30, 2020 shows a man wearing a facemask cycling past an elderly man who had died on the pavement near a hospital in Wuhan, China. (AFP / Hector Retamal)

This photo taken on January 30, 2020 shows a man wearing a facemask cycling past an elderly man who had died on the pavement near a hospital in Wuhan, China. (AFP / Hector Retamal)But at the same time many of us felt we had been here before. Journalists have a certain muscle memory when it comes to health epidemics and warnings of pandemics. Over the past 15 years some of us covered SARS, bird flu, swine flu and MERS. Other incredibly brave AFP colleagues donned full hazmat suits to report inside rudimentary hospitals in West Africa during the deadly Ebola outbreak in 2018 and in 2014. We had protocols, masks, goggles and other protective gear. This looked familiar right up until the moment it became very, very different.

A member of the South African Police Service (SAPS) enforces social distancing as he makes shoppers hold their hands out in front of them to ensure that they are at least one metre apart from one another while they queue outside a supermarket in Yeoville, March 28, 2020. (AFP / Marco Longari)

A member of the South African Police Service (SAPS) enforces social distancing as he makes shoppers hold their hands out in front of them to ensure that they are at least one metre apart from one another while they queue outside a supermarket in Yeoville, March 28, 2020. (AFP / Marco Longari)In the two months since our team was extracted from Wuhan on a French military plane, the COVID-19 pandemic has become perhaps the greatest crisis of modern times. It has upended the functioning of our societies and posed unique challenges for journalists committed to documenting and explaining the extraordinary new reality. We are used to challenging ourselves to tell complex stories. But how do we accomplish our mission when the story touches the lives of every single one of our 2,400 staff and when our overriding priority must be to protect them and their families? How do you do great journalism in an age of social distancing ?

Everything is different, but the commitment and passion of our journalists is unwavering. The pandemic has forced us to look into the abyss. It has made us confront what we are missing, and forced us to be creative and ingenuous. It has stripped our storytelling down to what is really essential and forced us to report with great humility.

(AFP / Aurélia Bailly)

(AFP / Aurélia Bailly)Virtually all our 200 bureaus and 1700 journalists are working remotely. Our Paris headquarters usually hums with over 1,000 people turning the wheels of the daily news cycle. Now there is just a skeleton of 30-40 people including vital security and cleaning staff. And the same pattern has been created in our offices all over the world as our teams have followed the destructive path of the virus from Asia to Europe and beyond. We have had a ringside seat on the journey. The early lessons picked up by our Asian teams have given us vital ammunition to fight this battle. We have surprised ourselves by realizing almost all our journalism can be managed remotely.

Street artist Angelo Picone hangs a solidarity basket ('Panaro solidare') in one of the deserted streets in the historic center of Naples on April 3, 2020. (AFP / Carlo Hermann)

Street artist Angelo Picone hangs a solidarity basket ('Panaro solidare') in one of the deserted streets in the historic center of Naples on April 3, 2020. (AFP / Carlo Hermann)Our enterprising technical teams scrambled to set up mass homeworking systems for our editing structures and embraced multiple online communication platforms to create a parallel and secure virtual office world. We have become used to boisterous kids and yapping dogs punctuating our conference calls as mastery of the mute button develops. Our coronavirus crisis team entered the frenzied laptop market to refresh our supplies and continues every day to dispatch hand gel and protective gear to needy bureaus around the world.

We told ourselves to prioritize and accept there would be things we could not do, and yet AFP's production did not falter as our offices emptied through March. We learned, we adapted and we continued to produce vital and important stories in different ways. This is a story that touches all of us, and all our journalists wanted to tell the part that touched their communities. It is as significant in Kinshasa or Baghdad as it is in Paris, the Italian town of Codogno or New York.

A vendor walks past a deserted street amid concerns over the spread of the COVID-19 coronavirus in Hanoi on March 26, 2020. (AFP / Nhac Nguyen)

A vendor walks past a deserted street amid concerns over the spread of the COVID-19 coronavirus in Hanoi on March 26, 2020. (AFP / Nhac Nguyen) Beirut, March 22, 2020 (AFP / Anwar Amro)

Beirut, March 22, 2020 (AFP / Anwar Amro)

Our shared database of global deaths, declared cases and people living under lockdown worldwide compiled with official data from all our bureaus has become one of the story’s most authoritative sources. It allows us to break stories faster and tell them in simple graphics or data-driven videos.

Our medical correspondents provide daily context and guidelines, as well as expert analysis to fill the void created by online rumours. Our economics team brings clear-headed analysis to the gyrations of global markets, spiralling unemployment figures and doomsday GDP projections.

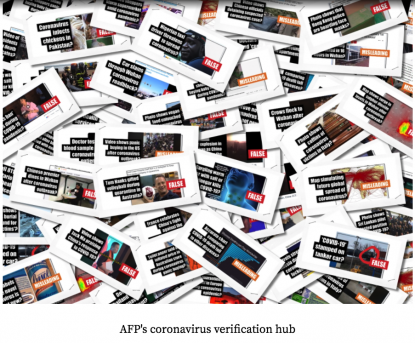

Our global fact-checking network has debunked some 600 pieces of COVID-19 misinformation and disinformation. The audience on our fact-checking site has exploded -– March saw almost as much traffic as the whole of 2019.

(AFP Digital Verification)

(AFP Digital Verification)Above all our 24-hour flow of reliable, measured and sourced information from all corners of the globe provides a vital framework to counter the speculation and fear-mongering. Our journalism has never been so vital, and so widely read and viewed.

Hospital Papa Giovanni XXIII in Italy, April 3, 2020. (AFP / Piero Cruciatti)

Hospital Papa Giovanni XXIII in Italy, April 3, 2020. (AFP / Piero Cruciatti)The pandemic is a uniquely human story. And yet one of the great paradoxes of this wrenching crisis is that it is often faceless.

The heroes, victims and protagonists are hidden by the walls of masks, goggles, visors, protective plastic, hospital wards, quarantine and containment measures.

(COMBO) This combination of pictures created on April 1, 2020 shows medical staffers on the frontline treating patients of the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic, posing for a picture while on break at al-Hakim General Hospital in Iraq's central shrine city of Najaf. - (Photos by Haidar HAMDANI / AFP) (AFP / Haidar Hamdani)

(COMBO) This combination of pictures created on April 1, 2020 shows medical staffers on the frontline treating patients of the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic, posing for a picture while on break at al-Hakim General Hospital in Iraq's central shrine city of Najaf. - (Photos by Haidar HAMDANI / AFP) (AFP / Haidar Hamdani)The man on the Wuhan street was likely somebody’s grandfather, but we dont know his story. We don’t even know if he had the coronavirus.

Hamm, Germany, April 8, 2020. (AFP / Ina Fassbender)

Hamm, Germany, April 8, 2020. (AFP / Ina Fassbender)Every day AFP journalists are battling to get behind the mask. Our photographer Ed Jones, inside a South Korean hospital treating COVID-19 patients, noticed the nurses wore bandages and plasters on their faces to protect against pressure sores of protective suits. Over a day he hung around the nurses’ rest area and managed to snap quick portraits as they passed. He also asked for a personal message for each caption. They still wore masks, but they were humanized.

A nurse-photographer Paolo Miranda was able to send us beautiful, intimate and heroic images of his work colleagues inside a hospital in Cremona in northern Italy. The emotion, exhaustion and moments of relief break through the protective swaddling. A long lens from a small boat bouncing in the Bay of Panama allowed us to see the distress for the first time of passengers waving from portholes on the marooned cruise liner Zaandam.

Cremone Hospital, southeast of Milan, March 13, 2020. (AFP / Paolo Miranda)

Cremone Hospital, southeast of Milan, March 13, 2020. (AFP / Paolo Miranda)We feel it is our mission to tell these vital stories, but we must do it as safely as we can. All reportage inside hospitals and places where we could encounter sick people is subject to a strict approval process by AFP chief editors. We always ask ourselves, is this really necessary ? Then we ask ourselves if we have all the correct protective equipment. And of course we make sure our journalists are comfortable with the mission. It is always voluntary.

Haidar Hamdani, our photographer in the Iraqi city of Najaf who has covered years of conflict, explains how he puts on old clothes and a blue plastic covering underneath the hospital-supplied protective suit. He then wears a medical mask covered by a larger gas mask, and luminous coverings over the latex gloves and shoe protectors. "I want to leave nothing to chance," he says.

The many stories and images that emerge from these courageous forays are public service journalism of the highest order. They are vital for understanding the crisis we face such as the herculean challenges confronting medical staff, the survival battles of the victims on ventilators and the lack of ventilators. When we enter a TGV hospital train in France or join South African police on the dangerous night-time streets of Johannesburg we are also explaining the response of governments and authorities. It is important to understand.

Mumbai, April 5, 2020 (AFP / Punit Paranjpe)

Mumbai, April 5, 2020 (AFP / Punit Paranjpe)Every day we are looking for human angles. Of course there are stories of anguish such as people dying anonymously in retirement homes, people barred from loved-ones' funerals and the chilling makeshift morgues on the streets of New York. There is the touching interview with the family of a French teenager taken by the virus.

Hospital in Mulhouse, in eastern France, April 5, 2020. (AFP / Sebastien Bozon)

Hospital in Mulhouse, in eastern France, April 5, 2020. (AFP / Sebastien Bozon) Alme, Italy, April 7, 2020. (AFP / Miguel Medina)

Alme, Italy, April 7, 2020. (AFP / Miguel Medina)But there are also great stories of endurance and even levity. Romans singing from their balconies or the Naples residents lowering food baskets to the needy. The lotto games that continue in Madrid with people shouting winning numbers from their windows. The Indian policemen bringing smiles with their bizarre red coronavirus helmets. And of course the nightly applause for health workers in many cities.

Madrid, March 28, 2020. (AFP / Gabriel Bouys)

Madrid, March 28, 2020. (AFP / Gabriel Bouys)We are constantly adapting. Our video journalists realised quickly that we did not have enough booms allowing us to hold microphones at a distance of two metres for interviews. It would take too long to order more and so many constructed their own using monopods or rods. We realised that strapping a mobile phone on a stabilizer and riding through the world’s great and deserted cities on bicyles or motorbikes created the most extraordinary video images.

The eerie deserted filmscapes of the Champs Elysees or Fifth Avenue were compelling viewing. As new cities are affected, we are replicating the formula. We also realised that our collection of drones was a powerful way of recounting the stillness and emptiness of these vast urban centres.

(AFP)

(AFP)One of the strangest aspects for us has been the grinding to a halt of the sporting calendar. Sporting events and championships make up a huge chunk of our daily diary. It is just gone. Our teams are of course writing about every aspect of the pandemic’s impact on different sports and analysing the way forward. We are writing about great exploits of the past. We are reporting on fitness and well-being. But we have no events and fresh images. We are marooned in a largely virtual and archive world.

Alejandro Lopez trains on a rooftop in Havana, Cuba, April 7, 2020. (AFP / Yamil Lage)

Alejandro Lopez trains on a rooftop in Havana, Cuba, April 7, 2020. (AFP / Yamil Lage)At the moment we feel perhaps the euphoria of the marathon runner after the first 10 kilometres. We are proud of what we have managed to achieve so far, but we realise there could be a very long way to go.

We are very conscious of the effect of the pandemic on our staff, both the mental pressure and the very real risk of physical illness. We are more aware than ever that many of our staff in the emerging world have unequal access to healthcare. We are also very aware that our clients are facing many of the same struggles. So far we believe we have had around 60 cases of suspected COVID-19 among our staff. We have had few hospitalisations and many people have returned to work. But we are not complacent. We see the full horror of this virus in our journalism every day.

Medical staff from Jilin Province (in red) hug nurses from Wuhan after working together during the COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak during a ceremony before leaving as Tianhe Airport is reopened in Wuhan in China's central Hubei province on April 8, 2020. (AFP / Hector Retamal)

Medical staff from Jilin Province (in red) hug nurses from Wuhan after working together during the COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak during a ceremony before leaving as Tianhe Airport is reopened in Wuhan in China's central Hubei province on April 8, 2020. (AFP / Hector Retamal)