Life in a time of Ebola

Beni, Democratic Republic of the Congo -- Take a deadly contagious disease that spreads on contact. Drop it into an area surrounded by jungle, where armed groups vie for control over remote corners. Add a population exhausted by decades of conflict, weary of outsiders and suspicious of Westerners clad in protective suits erecting camps to treat this illness, camps from which their loved ones often don’t come out alive.

I don’t think you could think up of a more complicated, dangerous place to have an Ebola outbreak than northeastern Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The Ebola outbreak in eastern Congo is now the second largest outbreak in history and has killed more than 249 people since flaring up in early August, according to official data. Or, more precisely, these are the people known to have been killed by the disease. There could be more, but NGOs can’t travel freely in the region, so no one really knows the exact toll.

A South African soldier from the United Nations Stabilisation Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO) reacts inside a military position as gun fire erupts close by on October 07, 2018 outside Oicha. - The town of Oicha is the site of constant attacks by the ADF rebel group and MONUSCO soldiers are often sent in to help the Armed Forces of the Democratic republic of the Congo (FARDC) in the fight against the rebel group. (AFP / John Wessels)

A South African soldier from the United Nations Stabilisation Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO) reacts inside a military position as gun fire erupts close by on October 07, 2018 outside Oicha. - The town of Oicha is the site of constant attacks by the ADF rebel group and MONUSCO soldiers are often sent in to help the Armed Forces of the Democratic republic of the Congo (FARDC) in the fight against the rebel group. (AFP / John Wessels)To give you an idea of just how murky this outbreak is you need to understand the context. The resource-rich North Kivu region is a remote area close to the border with Uganda and Rwanda. The soil here produces many of the minerals needed for electronic devices like smartphones and computers. This, plus its remoteness, has made it a haven for armed groups, both local and those from neighboring countries, with ever-shifting acronyms, allegiances and raisons d’etre.

What’s life like here? Take the main towns of Butembo and Beni. There are sporadic guerilla-style attacks popping up all over. Last time I was in Beni, a house was mortared and another attacked. One man was killed and four children were kidnapped. This was about a five-minute motorbike ride from where I was staying. It’s not uncommon to wake up at 5 am to gunfights nearby. I have a friend who is a local journalist. He is home by 6 o’clock every night because of the attacks. He goes from covering rebel attacks in the morning, to Ebola in the afternoon. Psychologically it’s very tough.

Butembo has its own complications. The town is surrounded by militias, so access to surrounding areas is very limited. Sometimes you need to establish contact with these militias before venturing out to fetch any patients outside the town. And in some cases, you need armed escorts to do so.

A South African soldier from the United Nations Stabilisation Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO), takes position at a main intersection to cut off fleeing Allied Democratic Front (ADF) rebels, after mortar and heavy machine gun fire are heard close by on October 05, 2018 in Oicha. (AFP / John Wessels)

A South African soldier from the United Nations Stabilisation Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO), takes position at a main intersection to cut off fleeing Allied Democratic Front (ADF) rebels, after mortar and heavy machine gun fire are heard close by on October 05, 2018 in Oicha. (AFP / John Wessels)The nature of the disease and its treatment only adds to the difficulties of treating it.

Ebola is a viral disease that spreads through contact. So patients need to be isolated and health workers need to trace people who have been in contact with them to see if they contracted it too. A single patient could have had a hundred contacts. That's a hundred people to follow up.

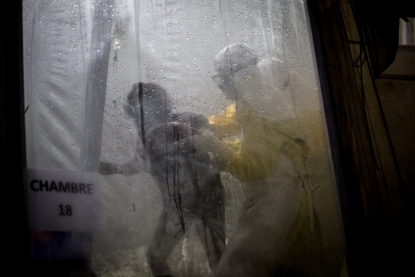

To isolate patients, NGOs set up centers where staff wear protective suits, covering them from head to toe so they don’t contract the disease. Ebola is a very aggressive virus, so often the people who go into these centers don’t come out alive. Those who die have to be buried with specific precautions as their bodies are highly contagious.

Health workers help a patient suspected of having contracted Ebola to her bed inside an Ebola Treatment Center (ETC) supported by the MSF (Doctors Without Borders) group, November 3, 2018, Butembo, Democratic Republic of the Congo. (AFP / John Wessels)

Health workers help a patient suspected of having contracted Ebola to her bed inside an Ebola Treatment Center (ETC) supported by the MSF (Doctors Without Borders) group, November 3, 2018, Butembo, Democratic Republic of the Congo. (AFP / John Wessels)Now take all that information and imagine it from the point of view of the people living here. You have probably fled your home at least once in your life because of armed conflict. Maybe you have fled two or three times, or more. Deadly attacks on your friends and neighbors are part of life. You can have an attack overnight and the next day, a person visiting the area wouldn’t even know it; life just goes back to normal.

Then people begin to die. One here, one there. Sometimes they die after experiencing gruesome symptoms like bleeding from the gums, eyes and ears. To add to this confusion, you have hundreds of NGO workers and journalists arriving in 4x4s in your small town. Places called Ebola Treatment Centers (ETC's) are set up, where people have to wear protective gear that look like space suits.

A health worker is seen in a mirror with his personal protective equipment (PPE) before entering the red zone of a MSF (Doctors Without Borders) supported Ebola Treatment Centre (ETC), where he will be checking up on patients on November 3, 2018 in Butembo, Democratic Republic of the Congo. (AFP / John Wessels)

A health worker is seen in a mirror with his personal protective equipment (PPE) before entering the red zone of a MSF (Doctors Without Borders) supported Ebola Treatment Centre (ETC), where he will be checking up on patients on November 3, 2018 in Butembo, Democratic Republic of the Congo. (AFP / John Wessels)Now imagine that one of your loved ones contracts Ebola and gets taken by people wearing these suits into this frightening place called an ETC. And then they pass and you are told that your loved one will now have to be buried in a certain way, a way that doesn't have anything to do with the traditions of your culture.

Health workers are seen inside the red zone at a newly build MSF (Doctors Without Borders) supported ebola treatment centre (ETC) on November 7, 2018 in Bunia, Democratic Republic of the Congo. (AFP / John Wessels)

Health workers are seen inside the red zone at a newly build MSF (Doctors Without Borders) supported ebola treatment centre (ETC) on November 7, 2018 in Bunia, Democratic Republic of the Congo. (AFP / John Wessels)In this context, it’s easy to see how there’s a lot of confusion over this disease. Why all of the sudden are there so many people dying? Why can’t you properly see the bodies after, why can’t you bury them as your people have done for generations?

All this, and with the upcoming elections adding even more volatility and uncertainty to the situation, it’s easy to see how rumors can spread. I’ve been shouted at myself. It was an old guy and when he saw me, he pointed at me and shouted “it’s you who brings Ebola here, to get money from Congo.”

Given this context, the work NGO's like Oxfam, MSF and ALIMA are doing here is unbelievable. Both in treatment and outreach. To be effective in an area like this, you have to talk to the communities, to explain to them what Ebola is, what are the symptoms, what are the treatments, precautions. It's an extremely difficult thing to do given the context of the area.

A health worker carries a four-day-old baby suspected of having Ebola, into a MSF (Doctors Without Borders) supported Ebola Treatment Centre (ETC) on November 4, 2018 in Butembo, Democratic Republic of the Congo. (AFP / John Wessels)

A health worker carries a four-day-old baby suspected of having Ebola, into a MSF (Doctors Without Borders) supported Ebola Treatment Centre (ETC) on November 4, 2018 in Butembo, Democratic Republic of the Congo. (AFP / John Wessels)And finally, there is the treatment itself. The treatment centers are built from scratch. You have doctors, logisticians and builders who fly in from all over for two months at a time. And during those two months, they just work around the clock to get these centers up and running as quickly as possible.

They’re doing a very difficult job in very difficult conditions, among people many of whom don’t believe in what they're doing.

The Ebola outbreak really hammers home the tragedy of eastern Congo.

I was standing on a corner, just trying to get simple daily life shots when a pickup truck drove by with a coffin in the back. There goes another Ebola death. It’s like an everyday thing here now. It’s so blasé in a way. People stop, look at it going by, and then carry on with their life.

Another time, I saw three people driving on a bike carrying a cross. It really touched me. Here are these three guys probably heading to a grave of a relative or a friend or a loved one. But it was nothing out of the ordinary. Nor was it the last time that I saw such a scene.

This blog was written with Yana Dlugy in Paris.

Three Congolese men ride a motorbike and carry a cross for a grave along the road linking Mangina to Beni on August 23, 2018 in Mangina, in the North Kivu province. (AFP / John Wessels)

Three Congolese men ride a motorbike and carry a cross for a grave along the road linking Mangina to Beni on August 23, 2018 in Mangina, in the North Kivu province. (AFP / John Wessels)