Three months with Chapo

New York -- This winter, I was lucky enough to attend the best show in New York, more captivating than a Broadway extravaganza or a Hollywood blockbuster. A theatrical marathon in 44 chapters, with a cast of characters who were as dazzling as they were macabre and who opened a window onto one of the deadliest and most lucrative businesses around the globe, the drug world. And all of it was true…

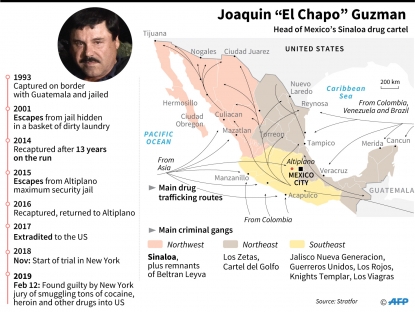

I am talking about the trial of 61-year-old Mexican crime and drug lord Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, who was found guilty of drug smuggling, money laundering and weapons possessions in a highly-publicized trial in New York City this winter.

A poster with the face of Mexican drug lord Joaquin El Chapo Guzman, reading Wanted, Again, is displayed at a newsstand in one Mexico City's major bus terminals on July 13, 2015, a day after he escaped from a maximum-security prison.

(AFP / Yuri Cortez)

A poster with the face of Mexican drug lord Joaquin El Chapo Guzman, reading Wanted, Again, is displayed at a newsstand in one Mexico City's major bus terminals on July 13, 2015, a day after he escaped from a maximum-security prison.

(AFP / Yuri Cortez)I have covered other of trials in New York -- from the nephews of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro who were convicted of drug trafficking, to corruption within the football governing body FIFA. But that of El Chapo has been the most surreal and exhausting. There were countless early mornings in the frigid New York winters when I had to spend hours in line, waiting to get into Judge Brian Cogan’s courtroom on the eighth floor of Brooklyn’s federal court building.

We weren’t allowed to bring in telephones or computers, so I covered the trial the old-fashioned, noble way, with only paper and pen.

There were so many people -- lawyers, prosecutors, federal agents, journalists, writers, scriptwriters, onlookers -- who wished to see with their own eyes the mythical Mexican drug kingpin that they all couldn’t fit inside the courtroom.

The first day was completely chaotic. There wasn’t enough room for everyone, so not only the courtroom but the “overflow room,” where the proceedings were transmitted on closed circuit TV, were both full. People mulled in the hallway between the two.

After that fiasco, reporters and others who wanted to get into the courtroom wrote down their names on a list as soon as they arrived, so the room would be filled on a first-come, first-served basis.

Despite these efforts, some reporters were still left out of the courtroom, so people began to arrive earlier and earlier. Some dedicated souls came as early as 1 o’clock in the morning for a trial that started at 9:30 am each day. The earliest I got there was 5:30 -- riding on a nearly empty subway, clutching my thermal cup filled with steaming black coffee.

Media positions themselves outside Brooklyn Federal Courthouse on November 13, 2018, when prosecutors and defense lawyers delivered opening statements. (AFP / Don Emmert)

Media positions themselves outside Brooklyn Federal Courthouse on November 13, 2018, when prosecutors and defense lawyers delivered opening statements. (AFP / Don Emmert)One reporter once came in the middle of the night with a large cardboard box that he placed on the icy sidewalk. He then rolled out his sleeping bag on top of it and dozed off. A prankster colleague took the opportunity to write on the box “Help me, I need this case to end!”

Almost every day, under rain, snow, hail or a barely-warm winter sun, my video colleague Diane Desobeau and the bureau’s photographers would mull for hours outside the building, waiting for the arrivals and departures of defense lawyers, prosecutors and especially Emma Coronel, El Chapo’s wife who would arrive with the clothes that her husband would wear that day.

The author (left) and video colleague Diane Desobeau (right) make the best of snowy circumstances as they wait to get into the Brooklyn courthouse for the El Chapo trial. (Photo courtesy of Laura Bonilla Cal)

The author (left) and video colleague Diane Desobeau (right) make the best of snowy circumstances as they wait to get into the Brooklyn courthouse for the El Chapo trial. (Photo courtesy of Laura Bonilla Cal)Aside from courtroom drawings, those were the only images that we could get of the proceedings, as cameras were not allowed inside.

Security measures for this trial were even more rigorous than usual at US courts. And with good reason -- the former head of the feared Sinaloa cartel, Chapo had twice escaped from Mexican prisons in spectacular breakouts and the authorities weren’t taking any chances that he would make it a hat trick in New York.

Taking no chances -- Mexican drugs kingpin Joaquin 'El Chapo' Guzman is escorted by a police motorcade across the Brooklyn Bridge on October 10, 2018, back to jail in lower Manhattan after his court appearance. Security was extra tight throughout the trial of the man who twice managed to escape from maximum-security prisons in Mexico.

(AFP / Timothy A. Clary)

Taking no chances -- Mexican drugs kingpin Joaquin 'El Chapo' Guzman is escorted by a police motorcade across the Brooklyn Bridge on October 10, 2018, back to jail in lower Manhattan after his court appearance. Security was extra tight throughout the trial of the man who twice managed to escape from maximum-security prisons in Mexico.

(AFP / Timothy A. Clary)First, we had to go through a metal detector on the ground floor, getting in line with dozens of newly-naturalized Americans who had arrived for that day’s swearing-in ceremony.

A second security check was installed in front of the courtroom itself, where we were greeted by agents with dogs trained to sniff out explosives and had to go through a second metal detector, this time taking off our shoes and belts to pass through.

We weren’t allowed to bring in cell phones or computers, a regular rule in US federal buildings that in this case became even more relevant because some of the government witnesses were in witness protection programs and even court artists couldn’t draw their faces. And the jury in this case was ‘anonymous’ -- their names weren’t released, it was forbidden to take pictures of them or to have their faces drawn by the court artist to prevent either Chapo and his associates from taking revenge or trying to bribe them.

Not even the handful of journalists who cover the Brooklyn court on a daily basis and are normally exempted from the no-cell rule could bring their phones inside.

Between this security check and the actual courtroom, there was a small room used by the defense team. A few days after the start of the trial, on a shelf in the room there appeared a statuette of Jesus Malverde, a bandit who roamed the Sinaloa region in Mexico in the late 1800s and is the patron saint of drug traffickers who is venerated by El Chapo. When we asked one of the defense lawyers, Eduardo Balarezo, who put it there, he insisted it had appeared out of nowhere. “It’s a miracle,” Balarezo told us, tongue firmly in cheek.

A statue of Mexican drug lord Joaquin 'El Chapo' Guzman, is displayed for sale near a bust of narco-saint Jesus Malverde, at his chapel in Culiacan, Sinaloa state in northwest Mexico, on February, 19, 2019. (AFP / Rashide Frias)

A statue of Mexican drug lord Joaquin 'El Chapo' Guzman, is displayed for sale near a bust of narco-saint Jesus Malverde, at his chapel in Culiacan, Sinaloa state in northwest Mexico, on February, 19, 2019. (AFP / Rashide Frias)A total of some 56 witnesses passed through Judge Cogan’s courtroom of wooden walls and pink marble, summoned by the government to reconstruct in great detail for the jury the life and work of one of the world’s most feared drug kingpins.

Throughout, the accused remained stone-faced while his wife Emma, a voluptuous brunette who reminded one of Kim Kardashian, blew him kisses and smiles while chewing gum and caressing her straight, long, black hair.

The wife of Joaquin El Chapo Guzman, Emma Coronel Aispuro, adjusts her hair as she arrives in court on January 14, 2019.

(AFP / Don Emmert)

The wife of Joaquin El Chapo Guzman, Emma Coronel Aispuro, adjusts her hair as she arrives in court on January 14, 2019.

(AFP / Don Emmert)The prosecution presented a veritable tsunami of evidence to the jurors -- more than 300,000 pages of documents and 117,000 audio recordings, as well as hundreds of photos and videos of both Chapo and his partners.

I often wondered whether the spectacular deployment, which cost US taxpayers tens of millions of dollars, was really necessary.

Without a doubt, convicting a man who has trafficked hundreds of tons of drugs into the US over a quarter of a century, was a feather in the cap of Washington’s long-running war on drugs that has up to now never managed to put such a well-known drug lord behind bars.

(AFP Graphics)

(AFP Graphics)But Chapo’s Sinaloa cartel is still at it, ruled by less-known people (including several of Chapo’s sons). Arms trafficking from the US to Mexico hasn’t stopped. The US drug use rate has increased, with overdose deaths having reached a record of 192 per day in 2017, the last full-year figures available.

Meanwhile on the other side of the border, Mexico last year had a record 33,000 intentional homicides, many of them linked to drug trafficking. This has directly affected our office in Mexico, which has worked in parallel with the New York bureau on this trial with reactions, reports from Sinaloa and analyses about the war on drugs and government corruption. In May 2017, our stringer in Sinaloa, Javier Valdez, a respected journalist and an expert in drug trafficking, was killed.

Over the months, I saw a chain of characters that would make any movie or novel proud -- Chapo’s former right-hand men, his secretaries, his IT guy, his Mexico City manager, accountant, two of his pilots, one of his hitmen, his main cocaine suppliers in Columbia. And one of his mistresses, who during testimony started crying uncontrollably while Chapo’s wife smiled mockingly at her. A narco novella had nothing on this trial.

The day the mistress broke down -- telling how she escaped from Mexican agents with Chapo running naked through a tunnel hidden under a bathtub in a house in Culiacan, both Chapo and his wife wore burgundy velvet blazers. It was as if they were sending a message to the former lover and anyone else who cared to listen -- we are a team.

Emma Coronel Aispuro, wife of Joaquin 'El Chapo' Guzman leaves court on February 11, 2019, in Brooklyn, New York.

(AFP / Kena Betancur)

Emma Coronel Aispuro, wife of Joaquin 'El Chapo' Guzman leaves court on February 11, 2019, in Brooklyn, New York.

(AFP / Kena Betancur)At the start of the 1990s, cocaine trafficking “was the best business in the world,” Miguel Angel ‘Gordo’ Martinez, Chapo’s forer treasurer and pilot, told the court.

"Gordo" recounted how the drug kingpin who was born into poverty and didn’t finish primary school had traveled for rejuvenation treatments in Swiss clinics, had a mansion facing the sea in Acapulco with a yacht called “Chapito,” ranches in each of Mexico’s 31 states as well as Mexico City, four jets, scores of women and a private zoo stocked lions and panthers and a little train to ferry visitors to stare at them.

In one of the most tragicomic parts of the trial, “Gordo” told of how his former boss ordered him killed three times after the two fell out -- first the assassins tried it by stabbing him, then by hitting him with a baseball bat, and then by throwing grenades inside his cell in a Mexican jail. The latest ‘attempt’ was eerie -- Chapo hired a mariachi band to serenade him through the night, playing a single song called “A fist of earth” some 20 times -- “What happened in this world/ there are no memories left/ when I’m dead I’ll take/no more than a fist of earth.” Apparently this was black humor on Chapo’s part -- the song was a favorite of his and with it, he was sending his former lieutenant the unmistakable message that his days were numbered -- although he had escaped death in the previous three attacks, his lungs and stomach were left badly injured and it was only a matter of time when he would return to dust.

Perhaps the most frightening witness of all was Juan Carlos “Chupeta” Ramirez, the onetime biggest cocaine supplier to El Chapo, who underwent countless plastic surgeries on his face and ears to evade capture. He told the court that with Chapo’s help, he had sent more than 400 tons of cocaine into the US, ordered the murder of 150 people and that after his arrest, Colombia seized a billion dollars from him. The scale of the narco trade truly came into focus with that testimony.

This combination of undated handout photographs obtained from Brooklyn federal court on November 29, 2018, shows a before (L) and after (R) plastic surgery picture of Colombian drug lord Juan Carlos Chupeta Ramirez Abadia shown to the jury during El Chapo's trial. (AFP / -)

This combination of undated handout photographs obtained from Brooklyn federal court on November 29, 2018, shows a before (L) and after (R) plastic surgery picture of Colombian drug lord Juan Carlos Chupeta Ramirez Abadia shown to the jury during El Chapo's trial. (AFP / -)In the US, members of the public are usually free to attend trials and Chapo's attracted some odd types eager to see in person the man who has been an inspiration for many drug traffickers.

Like a couple who was originally from Sinaloa but who has lived for the past 20 years in San Francisco. They decided to attend the trial to mark their 11th wedding anniversary in December. To celebrate their special day, they lined up at 4 am to see the man who was accused of ordering dozens of murders and himself executing rival drug dealers after savagely torturing them. Apparently the few days in December wasn’t enough for the star-struck couple, for they came back for more in January, hoping their presence would “lift his spirits.”

One day, I ran into a fictional Chapo as I lined up to see the real one. The Mexican actor Alejandro Edda, who plays Chapo in the Netflix series “Narcos: Mexico,” wanted to see in person the man he was portraying, to study his gestures and mannerisms.

When one of Chapo’s lawyers pointed him out, the real Chapo greeted the actor with a smile and a wave (though the 1.60 meter-tall kingpin (5’2”) later told his lawyers that he didn’t expect the actor to be so short).

Mexican actor Alejandro Edda, who played Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzman in Netflix's "Narcos: Mexico", arrives at the US Federal Courthouse in Brooklyn on January 30, 2019.

Mexican actor Alejandro Edda, who played Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzman in Netflix's "Narcos: Mexico", arrives at the US Federal Courthouse in Brooklyn on January 30, 2019.Another day, I sat next to a man who told me he had been imprisoned for drug trafficking and who insisted that Chapo was the victim of a plot.

Then there was the evangelical woman wearing a black ecclesiastical jacket and a Roman Catholic collar, skirt and high-heel boots. She always carried a Bible and knelt on the pink carpet of the courtroom to pray for Chapo. She was nicknamed “The Reverend” by the press.

Toward the end, when I thought I had seen everything and the days passed by in slow motion as we waited for the jury to reach a verdict, I began to chat with a man who first told the marshalls that he was a relative of Chapo. Then he told me he was his friend. Minutes later he was taken away in handcuffs -- a Spanish national, he was wanted on several arrest warrants for harassment and threats. We were told he would be deported back to Spain. When we asked one of Chapo’s attorneys, Jeffrey Lichtman, who the man was, he simply replied “a fake.”

Masks of the Mexican drug trafficker Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzman are pictured in a factory of costumes and masks, on October 16, 2015, in Jiutepec, Morelos State in Mexico.

(AFP / Ronaldo Schemidt)

Masks of the Mexican drug trafficker Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzman are pictured in a factory of costumes and masks, on October 16, 2015, in Jiutepec, Morelos State in Mexico.

(AFP / Ronaldo Schemidt)During breaks, Chapo’s lawyers -- all experienced criminal defense attorneys -- would chat amicably with reporters in the halls. In all, we waited 35 hours over six days for the jury to reach its verdict. After so much time, I was terrified of missing anything and once inside the courthouse, practically didn’t venture out beyond the security perimeter outside the courtroom.

With tensions high, misunderstandings were bound to happen. Once a colleague misunderstood an email from the prosecutor’s office and shouted “verdict!” A veritable flow of journalists, some without shoes, others without paper or pencil, surged up the stairs toward the courtroom. One couple threw their cell phones in the trash and under a bench and ran into the courtroom, breathless.

Turned out it was a false alarm. The colleague survived the incident unharmed, but was much ridiculed by the rest of us.

When the moment of truth finally came, I felt my heart jump to my throat. I was in the courtroom, with the eight sheets of the verdict ready to be read, with Chapo about five meters away and his wife Emma almost right next to me, dressed in a three-quarter-length emerald green jacket.

The color of hope, I thought. Or money.

The capo’s wife turned to a journalist sitting next to her.

“How do you say guilty in English?” she whispered.

This file handout photo released by the Mexican Interior Ministry on January 19, 2017 shows Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzman (center) escorted in Ciudad Juarez by Mexican police as he is extradited to the United States. (AFP / Ho)

This file handout photo released by the Mexican Interior Ministry on January 19, 2017 shows Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzman (center) escorted in Ciudad Juarez by Mexican police as he is extradited to the United States. (AFP / Ho)