Pride and craftsmanship

Rock Tavern, NY, United States -- The thing that struck me the most was just how proud everyone was of their work. Every person involved in the process of making the Oscars’ statuettes -- from the 3-D computer image to the carefully polished, stamped, cocooned pieces ready for shipping to Brooklyn to be plated in gold -- everyone took extreme care in what they were creating.

I suppose it’s only fitting that this amount of care would go into making the Oscar -- one of the world’s most recognizable trophies, bestowed upon the best in film since 1929.

A 24-carat gold Oscar statuette stands in front of a wax version at Polich Tallix Foundry. (AFP / Don Emmert)

A 24-carat gold Oscar statuette stands in front of a wax version at Polich Tallix Foundry. (AFP / Don Emmert)To tell the you the truth, I’m not much of a movie buff. But I’ve broadened my knowledge a bit with this assignment.

While I’ve obviously known what Oscars are (I even covered them once, many years ago) I never paid too much attention to the statuette. Then several years back, there was an opportunity to take pictures of it at a TV studio in New York and I got a close-up look.

It’s a beautiful piece -- a knight holding a crusader’s sword and standing on a reel of film with five spokes, symbolizing the five original branches of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences -- actors, directors, producers, technicians and writers.

It stands 13.5 inches (34.29 centimeters) tall, weighs 8.5 pounds (3.6 kilos) and there have been 3,048 of them presented since the first one was handed in 1929 to a guy named Emil Jannings who won for best actor in “The Last Command” and “The Way of All Flesh.”

The original Oscar was cast in bronze and coated in gold. Over the years it has traded manufacturers and for 33 years until 2015, it was made at a Chicago trophy producer, where it was cast in something called britannia metal and plated in gold. But in 2015, the Academy switched manufacturers and now its home is the Polich Tallix fine art foundry in the upper Hudson Valley in New York state. Which is where I got a close-up look at the 50 statuettes being prepared for this year’s ceremony.

(AFP / Don Emmert)

(AFP / Don Emmert)One of the things I love most about shooting features is the opportunity to see everyday people doing what they do and to talk to them. As a news photographer, most of your time is spent documenting events. Which is great and has its own charms. But you don’t really get to talk to people. But shooting a feature is a great opportunity to make a connection and interact with all sorts of people.

The foundry shares a huge warehouse with a few other artists. It produces all kinds of work. When we were there in January, they were also working on a large Jeff Koons piece, which gives you an idea of the calibre of their work.

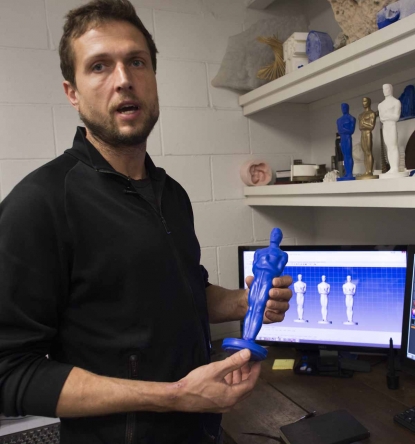

Daniel Plonski at his office. (AFP / Don Emmert)

Daniel Plonski at his office. (AFP / Don Emmert)There are about nine to 10 people, all very laid back, very friendly, working on the statuettes. They take about three months to manufacture and there are many stages involved. When the foundry got the commission, they held consultations with the Academy and decided to both return to casting the statuettes in bronze and to return Oscar closer to his original incarnation. Over the years, slight changes had crept into the design. So the people at Polich Tallix scanned the original Oscar designed in 1928, compared it with the Oscar of 2015 and came up with something in the middle.

To tell you the truth, I can’t really tell the difference between the various incarnations. But the craftsmen at the foundry sure could.

At one point during the shoot, Daniel Plonski, the guy who designed the latest Oscar incarnation as a 3-D computer model, came into the room while I was photographing a statuette. “That’s last year’s version,” he said immediately. I could have photographed them for hours and not have been able to tell the difference, but he knew within a second.

And that’s the way it was with everyone every step of the way. You could just tell that this was their baby and how proud they were of it. And there were quite a bit of steps.

It begins with the 3-D design. Once that is ready, it is printed on a 3-D printer in wax. Then that wax statuette is made into a silicon mold. Then the silicon mold is made into a ceramic mold and the ceramic mold is filled with molten bronze. Once cool, the statuettes go through a series of polishings and are stamped with a serial number. Then they’re sent off to a place in Brooklyn to be coated in 24-carat gold.

There is a different person responsible for each step of the production process and each person didn’t just do his or her job, but really took care with it. The guy who was polishing the pieces, Leo Sotelo, explained to me the various polishes that he had -- to remove a scratch you use this one, to buff you use that one. And you could just tell how into it he was.

Leo Sotelo carefully polishes an Oscar statuette. (AFP / Don Emmert)

Leo Sotelo carefully polishes an Oscar statuette. (AFP / Don Emmert)The guy stamping the serial number didn’t just punch it in as if on an assembly line. He took care to stamp them just so. Like an artist.

In the end, this assignment turned out exactly what I hope for features. I got to see normal, really nice people working on these amazing, iconic statuettes. Artisans who took pride in their work and were careful and precise in everything that they did.

This blog was written with Yana Dlugy in Paris.

(AFP / Don Emmert)

(AFP / Don Emmert)