Children of the quarry

OUAGADOUGOU - Since moving to Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso’s capital, I’ve taken to roaming the streets late at night, when the city empties and takes its last breaths before settling down to sleep. It’s during the calmness of the night that I often see and feel things that pass you by during the hussle of the day.

One such night, I get lost in the streets of the Pissy neighborhood in the west of the capital, where a strong smell of smoke overcomes me. That was my first contact with the granite quarry, which sustains numerous families in the neighborhood.

I come back the following morning. I see a road of red rocks, pyramids of white stones and sand. There are lots of trucks. And swarms of children.

A group of them announces my arrival. They run behind me, yelling “Nasara! Nasara!” (“A white woman! A white woman!”) They gather in front of me. One salutes me -- he folds his arms across his chest and slightly bends his knees. Another mimics him. The greeting is a sign of respect that they learn at school and at home, a friend explains to me.

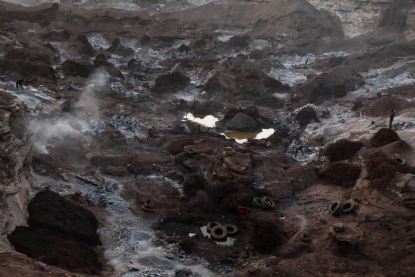

The quarry. (AFP / Nabila El Hadad)

The quarry. (AFP / Nabila El Hadad)I sit at a cafe, a huge blue metal box looking out onto the sandy road. Men and children are watching an old Jackie Chan movie on the television. Mamoudou, the barkeep, welcomes me and gives me some water. An old Khadafi and Ronaldinho stickers adorn the fridge.

Mamoudou is also a buyer of granite, which he resells to businesses and individuals alike. He thinks that I am here to buy. I tell him that I am a journalist and would like to do a story on the mine and that I currently live in Ouagadougou. This reassures him and he takes me down to the mine to introduce me around.

I walk through rows of bamboo sticks covered by cloth -- sun protection that the women put up every morning and take down each night. A little further away, I see a group of women sorting stones. They walk with ten kilos of stones on their heads. Some also carry a child on their back.

(AFP / Nabila El Hadad)

(AFP / Nabila El Hadad)From above, the quarry looks like an abyss. The first time that I descend into it, hot air fills my lungs. Silhouettes move through clouds of fine powder. The clouds are the toxic gases released by tires that are burned to weaken the stone before it’s broken. The mine is filled with the heavy thuds of hammers and pickaxes, interspersed with coughing. Most of the people working there do so without any masks or gloves.

Walking down a winding path into the mine, a woman calls out to me in Mossi, the language spoken by the country’s Mossi ethnic majority: “How are you?”

“Fine,” I answer. “How is the family?”

“Fine, fine,” she answers, taking my hand.

The encounter gives me confidence to take out my camera -- I usually like to have the people get used to me first before starting to take their pictures. I take a few pictures of this old woman, with her agreement. Then suddenly another woman approaches me, shakes my hand and touches her mouth with it several times -- she wants me to give her something to eat in return for allowing me to take her picture. Other women follow suit.

My camera is regarded as a sign of wealth here, a foreign intrusion. One group of workers is hostile as soon as they see me. Their distrust spreads like wildfire to the others.

Mamoudou is still at my side. He explains that “when the whites came here, they always brought aide, clothes, medicine. They gave something, then they left.” Then there was a group of European tourists who came once, took some pictures and left. The locals think that whites think of them as a tourist attraction.

I put my camera away and decide to proceed slowly. In Burkina Faso, conversation is an art form, so perhaps best to start there.

(AFP / Nabila El Hadad)

(AFP / Nabila El Hadad)The first day I don’t take any pictures, but keep the camera around my neck. I return to the mine the following day. I greet the women and sit next to them. Here, you start by giving your last name -- you’re a descendant of a certain line first, an individual second. We talk about the meaning of names. Mine, of Arab origin, means “The Blacksmith.” An occupation both respected and feared, even if blacksmiths are more and more rare today. In the Mossi language, my first name means “little chief.” The women laugh, convinced that I have Burkinabe origins.

I take a hammer and strike the rocks. I try and carry the rocks on my head like they do. “It’s hard,” one of them tells me. I agree.

The woman wants to take my picture. I show her how to work the camera. She looks at the photo and smiles. The other women do the same. Little by little, my camera begins to be a bit less menacing and foreign. This is how I take my first pictures, in between talking, often helped by a child or a teenager speaking the French they learned in school.

Each day, around a thousand people descend into the mine, which has expanded over the past 20 years. They come back to the surface with a tray of granite pieces that they will resell for about 50 eurocents each. They earn from one to two euros per day.

(AFP / Nabila El Hadad)

(AFP / Nabila El Hadad)Fifteen-year-old Amy knows the mine like the back of her hand. Dozens of children like her break the stones, from sunrise to sundown, during weekends and school holidays. Those who don’t go to school work there all year long. Amy tells me that families work together, each working their scrap of land. Children come and help their parents to increase the family’s take, which will go toward buying everything from the basics to school supplies.

The photos that I ended up taking reveal more than just poverty. They reveal that the mine is also a place to learn skills and autonomy and a substitute for school in a country where too few children get the chance to attend classes.

There is one scene from the time that I have spent at the mine that stands out. Two boys, seven years of age, fill goblets with small granite stones. Their skin and clothes are covered by a fine white powder. Their gestures are exactly the same as those of adults.

(AFP / Nabila El Hadad)

(AFP / Nabila El Hadad)At first I think they’re playing and imitating the adults, like children the world over. But ten minutes later, one of the boys gets up and sits in front of a pile of granite. He takes a hammer and begins to break the stones with his tiny hands that suddenly seem much older.

Since that first visit, I have come to visit once or twice a week. Sometimes just to say hello. Sometimes, when I’ve stayed away for too long, I receive a call from one of the women at the mine. “It’s been two days. Have you forgotten us?”

(AFP / Nabila El Hadad)

(AFP / Nabila El Hadad)