Turkey divided after a summer of blood

Ankara, November 23, 2015 -- It all started on a balmy early summer’s evening on June 5.

I had been sent to cover the final election rally of the pro-Kurdish Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP) in the main southeastern city of Diyarbakir ahead of the June 7 poll. Thousands filled the central square in a blaze of colour to listen to the charismatic HDP leader Selahattin Demirtas, who had emerged as a key player in the campaign, seeking to broaden the party's appeal to a wider cross-section of Turkish voters as well as Kurds.

Suddenly, an explosion shook the square. I initially didn't think it was a bomb and a party official on stage told the crowd it was a blast from a nearby generator and called for calm. But about 10 minutes later came a second blast, suggesting it was something much more serious.

The scene of the Diyarbakir rally moments after the blast. (AFP / Ilyas Akengin)

The scene of the Diyarbakir rally moments after the blast. (AFP / Ilyas Akengin)I was just 50 metres away from the very centre of the explosion, and witnessed all the chaos in the air, the wailing sirens of the ambulances mixed with screams, the blood-covered wounded leaning against trees or being carried away on the shoulders of friends or comrades. People in the crowds were panicking and rushing in all directions. Some shouted in fear "Daesh is here!"

Ambulances rushed to the scene but angry protesters were kicking them and then clashes erupted between stone-throwing Kurds and security forces. I ran fast to dodge the tear gas and report to the bureau in Istanbul.

Four people died and more than 100 people were injured in an attack that in itself was unprecedented in Turkey’s recent political history. And it was only the start.

Relatives mourn a victim of the deadly Diyarbakir blasts in early June. (AFP / Bulent Kilic)

Relatives mourn a victim of the deadly Diyarbakir blasts in early June. (AFP / Bulent Kilic)Midday, July 20. It had been an unusually calm morning for news in Turkey but then first reports came in of an explosion at a small rally of pro-Kurdish activists in the town of Suruc on the Syrian border. Many casualties. Then the first fatalities confirmed. Eventually, the toll would rise to 34 and the government would blame the attack on Islamic State jihadists.

After the Suruc bombing, the government launched air strikes on IS targets. And then the firepower also targeted the Kurds in the southeast and in Iraq after the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) shot dead two policemen in their sleep, accusing them of collusion with IS. The government declared a “war on terror” against IS, the PKK and Marxist radicals but primarily targeting the Kurdish rebels who struck back with deadly attacks that according to official media have now killed over 150 police and soldiers.

The southeastern town of Silvan, following clashes between government and Kurdish militants forces on November 10. (AFP / Ilyas Akengin)

The southeastern town of Silvan, following clashes between government and Kurdish militants forces on November 10. (AFP / Ilyas Akengin)Turkey was back in a vicious cycle of violence with scenes reminiscent of the 1990s when fighting between the PKK and security forces reached its peak. As a student then, I remember watching the nightly bulletins with my family -- the broadcasts showing funerals of fallen police and soldiers almost on a daily basis, with the red and white crescent Turkish flags draped over "martyrs" coffins and relatives screaming in grief.

Now, after several years of relative calm, both the PPK and President Recep Tayyip Erdogan were tearing up a ceasefire we hoped had ended that bloodshed. In the past, being "martyred" was an honour. Today, relatives at the funerals of the fallen servicemen publicly berate government ministers for the loss of their loved ones.

Protesters rally against the deadly October twin blasts in Ankara. (AFP / Ozan Kose)

Protesters rally against the deadly October twin blasts in Ankara. (AFP / Ozan Kose)But the worst single act of violence was still to come. My city, Ankara, the Turkish capital where I was brought up and studied, had always been a beacon of calm in the country, at least compared to the frequent chaos in Istanbul. While tourists flock to Istanbul, Ankarans love their city for its sense of community, its hot dry summers and relatively few traffic jams. Ankara has been shaken by attacks in the past, but nothing comparable to the events of Saturday, October 10.

Two suicide bombers blew themselves up in a crowd of peace activists, many of them Kurdish, preparing for a rally near the city's main train station. Initial reports put the death toll at at least 20, and then it shot up to over 100 -- making it the worst atrocity ever on Turkish soil.

Video grab of the moment an explosion ripped through a crowd of peace activists in Ankara in October. (AFP / Dokuz8 News Agency)

Video grab of the moment an explosion ripped through a crowd of peace activists in Ankara in October. (AFP / Dokuz8 News Agency)It was carnage, with witnesses giving gruesome accounts of body parts on the ground, the foul smell of burnt human flesh, survivors covering the dead using only the paper banners of the protesters. Some of the wounded were taken to hospital in a traffic police car whose windows were shattered by grief-stricken protesters. Some witnesses even said they saw remnants of human remains at the site days after the bombing. Authorities banned the broadcast of images from the scene.

In the aftermath of attacks in New York, Madrid, London or Paris, societies pulled together in a show of unity. But the Ankara atrocity appears to have torn us even further apart. The HDP -- whose activists were again targeted in Ankara -- accused the government of responsibility for turning a blind eye to IS. The government meanwhile insinuated that Kurdish militants had attacked their own.

Victims of the October twin blasts in Ankara following the explosions. (AFP / Adem Altan)

Victims of the October twin blasts in Ankara following the explosions. (AFP / Adem Altan)What struck a deep chord with me was to see football fans whistling and jeering and shouting "Allahu Akbar!" (God is greatest!) at a Euro 2016 qualifier in the central city of Konya when the national teams from Turkey and Iceland lined up to observe a minute's silence for the Ankara victims.

The Turkish team eventually won the game. But all the booing -- in the hometown of Rumi, a 13th century philosopher of Islam who preached tolerance -- was a startling example of how Turks have lost their sense of unity and even failed to come together to mourn their dead.

Some nationalist Turks speak of revenge: "What about our police and soldiers who were killed by terrorists?"

The polarisation of my country took another worrying turn ahead of the November 1 election, with an escalation of attacks and police raids against media outlets and journalists who oppose Erdogan and the government. During the campaign, state television gave almost blanket coverage to AKP events but air time was severely limited for opposition figures.

Plain clothes police detain a student at Istanbul University in early November, after the ruling party regained its parliamentary majority. (AFP / Ozan Kose)

Plain clothes police detain a student at Istanbul University in early November, after the ruling party regained its parliamentary majority. (AFP / Ozan Kose)The media clampdown has continued since the AKP's surprise election win in the November poll. The charges against the offending journalists are almost invariably "plotting a coup" "attempting to bring down the government" or some form of "terrorism", even if the prosecution is just over a satirical magazine cover.

Readers are pushed into two extremes. Newspapers either toe government line or bash the government to the point of caricature. For ordinary Turks, it is almost impossible to have access to objective news.

The AKP upset most predictions in November when it won by a landslide and won back the parliamentary majority it had lost in June after a campaign that promised fearful voters it would ensure security and stability.

When I interviewed Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu ahead of the June election, he boasted: "I am the only party leader who can tour all 81 cities in Turkey".

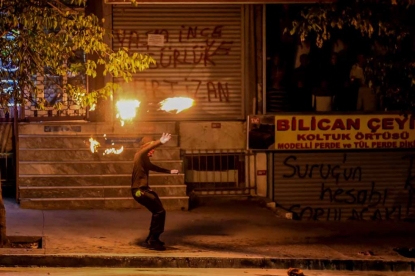

Protests in Istanbul in October. (AFP / Ozan Kose)

Protests in Istanbul in October. (AFP / Ozan Kose)The coming weeks and months will be a test for Turkey's leaders to embrace each and every citizen, to try to bridge the deep divide in our society. Older generations fear a return to the anarchy of the 1970s when fighting between left-wing and right-wing groups paralysed the country. I hope we are not going back to those dark days.

In 2008, Turkey's renowned filmmaker Nuri Bilge Ceylan dedicated his award for best director at the Cannes Film Festival to "my beautiful and lonely country, which I love passionately". But I now fear for the future of my beautiful and lonely country, which remains alarmingly uncertain despite all the government's proclamations.

Fulya Ozerkan is an AFP reporter based in Ankara. Follow her on Twitter.

Storm clouds gather over Istanbul, August, 2014. (AFP / Bulent Kilic)

Storm clouds gather over Istanbul, August, 2014. (AFP / Bulent Kilic)