Flight 847, into the hell of Beirut

MADRID, June 12, 2015 – At first I thought it was a joke. Another hijacking, this time of an American plane?

Three days earlier I had watched three hijackers blow up a Jordanian Boeing aircraft at Beirut airport, after forcing it to travel to Cyprus and back. They then vanished on board a Range Rover into a Shiite area of the city. A day later a young Palestinian threatened to set off a hand grenade on a flight from Beirut to Cyprus, surrendering after he obtained a passage to Jordan where he was arrested.

For an American plane to be in Beirut was unthinkable in itself. Suicide attacks on the American embassy and later on the Marine Corps barracks had forced the United States to pull out of the country the previous year along with the multinational peacekeeping force deployed there in 1982.

Nineteen American passengers are released in Beirut on June 14, 1985. (AFP Photo / Nabil Ismail)

Nineteen American passengers are released in Beirut on June 14, 1985. (AFP Photo / Nabil Ismail)That same week, a 54-year-old American professor named Thomas Sutherland had been kidnapped, becoming the seventh US hostage held in Lebanon.

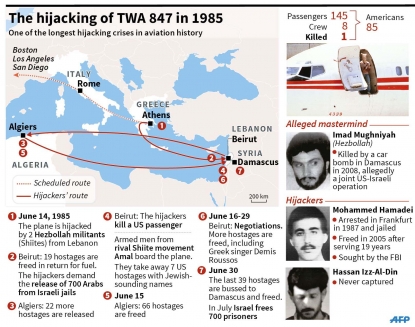

On Friday June 14, 1985 Flight 847 of the US carrier TWA was travelling between Athens and Rome with eight crew and 145 passengers on board - 85 of them American - when it was diverted towards Beirut airport, opening one of the longest hijacking crises in aviation history.

Two Lebanese Shiites – later identified as members of the Iranian-funded Hezbollah - were threatening to execute passengers unless they obtained the liberation of all Arabs held in Israeli jails. In the spring of that year, as it pulled out of most of Lebanon following a three-year occupation, Israel had taken with it more than 700 Lebanese and Palestinian prisoners.

After landing in Beirut the hijackers released 19 passengers including women and children, who evacuated the aircraft via an emergency slide. They then forced the pilot to take off again for Algiers, where to our relief another 22 passengers were freed.

Year 10 of Lebanon’s civil war

The call to prayer rang out in the evening air. The sweet scent of plumeria mingled with the reek of burning garbage, which no one had collected for a long, long time. In the distance you could hear the explosions and gunshots of the so-called “War of the Camps” that had been raging for three weeks.

The hijacked TWA Boeing, at Algiers airport on June 15, 1985 (AFP Photo / Philippe Bouchon)

The hijacked TWA Boeing, at Algiers airport on June 15, 1985 (AFP Photo / Philippe Bouchon)The Shiite Amal militia were besieging the Palestinian camps of Sabra and Shatila near the airport, to root out the last remaining fighters of the Palestine Liberation Organisation. They were trying to prevent the PLO guerillas – chased out of Beirut following the Israeli invasion in 1982 – from regaining a foothold in the city.

The camp siege had fanned tensions between Shiites and Druzes – traditional allies of the Palestinians – and there was sporadic fighting between the two factions in the streets of west Beirut. That same morning, 23 people were killed and 36 others injured in a suicide car attack against a Lebanese army position.

By that point, at AFP’s bureau in Hamra street in the city’s west, cut off from the Christian part of the city by a demarcation line, we were on our knees. But Henri, Selim, Nabil, Jacqueline, Hani and the rest of the team, however drained by a decade of war, were holding on under the leadership of the bureau chief Sammy Ketz.

That was the chaos towards which the TWA Boeing 727 returned the following night.

Shiite demonstrators at Beirut airport on June 21, 1985 (AFP Photo / Mohammed Attar)

Shiite demonstrators at Beirut airport on June 21, 1985 (AFP Photo / Mohammed Attar)And then, tragedy struck. The hijackers executed a 24-year-old passenger, the US Navy diver Robert D. Stethem, putting a bullet in his head after a savage beating. They threw his body out onto the runway.

The hijackers hijacked

We would later learn that a dozen men had come on board that night, taking away a group of passengers with Jewish-sounding names to the southern suburbs of Beirut. The Amal movement, led by Lebanon’s then justice minister Nabih Berri – today the parliament speaker – had hijacked Hezbollah’s hijacking.

On Saturday, June 15, the plane left once again for Algiers, its fuselage stained with blood.

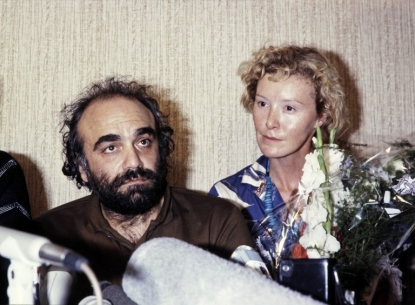

Greek singer Demis Roussos and his companion Pamela Smith following their release in Beirut on June 18, 1985

(AFP Photo / Joel Robine)

In Greece meanwhile, the police released an accomplice of the hijackers – a man named Ali Atwah who had failed to get a seat on flight 847 and had been arrested at Athens airport. There were a number of Greeks among the hostages – including the singer Demis Roussos. Ali Atwah was put on a plane for Algiers, where the hijackers went on to free 66 passengers.

The TWA Boeing – which journalists were by that point dubbing ‘Travel with Amal’ – took off again bound for Beirut, for the third and last time.

The airport was plunged into darkness, swarming with Kalashnikov-wielding militiamen in lieu of customs officials. We were hidden inside an airline’s office, along with the photographer Patrick Baz and the reporter Roger Auque, both young freelancers at the time.

From time to time a flare would light up the sky, out at sea – revealing the dark silhouettes of the Israeli patrol boats cruising off the coast. Amal had decreed a general mobilisation, allegedly for fear of a commando operation to free the hostages.

(AFP Photo / Nabil Ismail)

(AFP Photo / Nabil Ismail)We listened in, over the airport communications system, to the surreal conversations taking place between the hijackers and the control tower.

“If you don’t bring us food, I’ll go and get it myself from home.”

“Tell my mother I want a garlic shish-taouk (chicken kebab)”.

Patrick translated as I relayed the information by phone to the AFP bureau. But a luggage handler – Kalashnikov in hand – suddenly stepped in through the window. A light on the phone switchboard had given us away. Game up.

Two hijackers inspect the underside of the TWA Boeing in Beirut on June 19, 1985 (AFP Photo / Nabil Ismail)

Two hijackers inspect the underside of the TWA Boeing in Beirut on June 19, 1985 (AFP Photo / Nabil Ismail)Nabih Berri had ordered all foreign witnesses out of the airport that night to be able to move the hostages around under cover of darkness. By morning, only a handful would remain on board the aircraft.

Saved by lady's underwear

As we headed from the airport, we ran into an Amal patrol. The militiamen, clearly on edge, searched Roger Auque’s car and came across a picture of the Virgin Mary marked with the emblem of the Lebanese Christian militias.

Roger had just bought the car in East Beirut – without checking the contents of the glove compartment. Patrick Baz, the only one of us three who spoke Arabic, was also the only one who fully realised quite how dangerous our situation was.

But as they continued their search one of them pulled out a pair of lady’s underwear: “And who do these belong to, then?” Everyone burst out laughing – and the ice was broken. We were free to go, thanks to Roger the incorrigible lady’s man.

US hostages are presented to the press by their captors on June 20, 1985 at Beirut airport (AFP Photo / Joel Robine)

US hostages are presented to the press by their captors on June 20, 1985 at Beirut airport (AFP Photo / Joel Robine)On Thursday, June 20, Amal convened a news conference in the airport’s cafeteria. Five passengers were brought before the press – at the narrow end of a long table. There followed an extraordinary commotion as photographers massed on either side tried to take pictures – some of them lying flat on the table. Exasperated, the militiamen took their hostages away again.

Tragedy turned to farce

They brought them back a few hours later, this time positioning them so they could be photographed without starting a riot. The spokesperson for the hostages, Allyn Conwell, pleaded with the press to show a little more discipline. He then read out a statement echoing the hijackers’ request for the release of the Lebanese prisoners, “held hostage in Israel”.

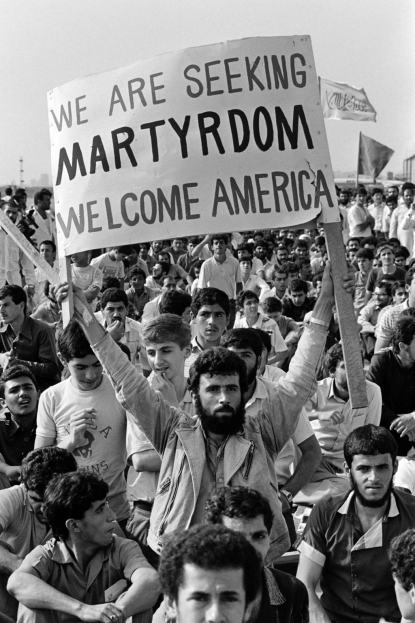

The next day, 2,000 Hezbollah militants rallied outside the grounded aircraft, egged on by three masked hijackers on the boarding ladder.

An anti-American demonstration at Beirut airport, in presence of the hijackers of TWA Flight 847, on June 21, 1985

(AFP Photo / Joel Robine)

As the negotiations dragged on, more hostages were released, one by one, among them Demis Roussos. Amal was selling interviews with remaining captives to US news channels. Meanwhile the hijackers could be seen moving around freely, on and off the Boeing.

Israel was only prepared to free its Lebanese prisoners if explicitly asked by the United States. Washington was refusing to give in to blackmail. But Syria, whose troops still occupied part of Lebanon back then, would have a role to play.

TWA captain John L. Testrake talks to reporters from the cockpit, as a hijacker holds him at gunpoint,

on June 19, 1985 at Beirut airport (AFP Photo / Nabil Ismail)

On Sunday, June 30, after 17 days in captivity, the last 39 hostages were freed – in Damascus, where they had travelled by bus.

Seated around a flower-bedecked table in the Sheraton hotel, they thanked Syria for its part in their release and voiced sympathy for their captors, saying they had shared the same emotions for weeks on end. A classic case of Stockholm syndrome, judged analysts in Washington.

In a final, surreal touch, it turned out that Amal had laid on a buffet for the hostages the night before, by the pool of the Summerland club in west Beirut – without any of the journalists who were staying at the luxury venue noticing.

Lebanese prisoners are released from Atlit prison in Israel on September 10, 1985 (AFP Photo / Kamel Lamaa)

Lebanese prisoners are released from Atlit prison in Israel on September 10, 1985 (AFP Photo / Kamel Lamaa)A few days later, Israel released more than 700 Lebanese prisoners.

One of the two initial hijackers, Mohammed Ali Hamadei, was arrested two years later in Frankfurt while transporting explosives. He served 19 years in jail in Germany, until his release in 2005, and is still wanted by the FBI. His accomplice Hassan Izz-Al-Din was never found.

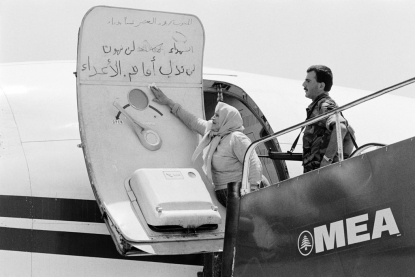

A Lebanese woman cleans off slogans written by hijackers on the door of the hijacked TWA plane, on July 6, 1985 at Beirut airport (AFP Photo / Mohammed Attar)

A Lebanese woman cleans off slogans written by hijackers on the door of the hijacked TWA plane, on July 6, 1985 at Beirut airport (AFP Photo / Mohammed Attar)Imad Mugniyah – a senior Hezbollah figure already blamed for a string of bloody attacks from Beirut to Buenos Aires – was indicted by a US court as the mastermind of the hijacking of Flight 847. Mugniyah was killed in a car bombing in Damascus in 2008, described by both the Washington Post and Jerusalem Post as a joint US-Israeli operation.

TWA filed for bankruptcy in 2001 and was subsequently acquired by American Airlines.

Patrick Baz is currently AFP’s chief photo editor for the Middle East and North Africa.

Sammy Ketz has returned to Beirut where he is once again AFP’s bureau chief.

Roger Auque died of cancer in 2014.

Patrick Rahir is currently AFP bureau chief in Madrid

A billboard pays tribute to the Hezbollah military leader and mastermind of the hijacking of TWA Flight 847, Imad Mugniyah, in Beirut on September 26, 2008 (AFP Photo / Ramzi Haidar)

A billboard pays tribute to the Hezbollah military leader and mastermind of the hijacking of TWA Flight 847, Imad Mugniyah, in Beirut on September 26, 2008 (AFP Photo / Ramzi Haidar)