In bed with Ebola

KAILAHUN, Sierra Leone, Sept 3, 2014 - At 4:00am in an Ebola hot zone - when you feel flushed, a little run-down and itchy from the prickly rash developing on your ankle - paranoia can creep in.

Did that kid touch me on the arm? Did that old guy who was spitting everywhere look sick? Did I touch my face before washing my hands after that interview? Is this a headache coming on? Is this a fever?

"Hot zone" is a term virologists use for the centre of an outbreak of a maximum Level Four Biological Hazard - a "hot agent", the kind of pathogen than can end civilisations.

Ebola is in exulted company in the "hot agent" category, along with weaponised anthrax and smallpox. It's not much of a choice, but I'd rather be exposed to either of those.

Sierra Leonese government burial team members disinfect the body bag of an Ebola victim at the Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) facility in Kailahun, on August 14, 2014 (AFP Photo / Carl de Souza)

Sierra Leonese government burial team members disinfect the body bag of an Ebola victim at the Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) facility in Kailahun, on August 14, 2014 (AFP Photo / Carl de Souza)Ebola Zaire, the species of the virus ravaging west Africa, is transmitted through bodily fluids and there are many ways it can kill you if you are not one of the minority of patients strong or lucky enough to survive infection.

The easiest of these involves days of extreme vomiting and diarrhoea, coupled with an agonising headache and a fever that will make you feel like you are being moved repeatedly between an oven and a deep freeze.

The symptoms are more gruesome in the patients that "crash and bleed out", their insides reduced to soup long before they slip away.

After 11 days travelling in Sierra Leone, one of the worst-hit countries in an epidemic which has killed more than 1,500 people across west Africa, I was ready to come home.

Viewing on a mobile device? Click here to open video in a new window.

I was the writer in a three-man multimedia team from AFP - the agency's first to report from the impoverished west African nation - which included video journalist Samir Tounsi and photographer Carl De Souza, who made for good company in a week of ups and downs.

We assessed the situation in Freetown, surprised by how on edge the city seemed, despite experiencing just one death.

We travelled to the hot zone in a banger with a rusting, smoky engine and no radio, listening to iPods or staring out at the endless savannah, which gives way to thick rainforest as you approach the east.

We had expected checkpoints. Our destination -- the far-eastern districts of Kailahun and Kenema where hundreds have died -- was under quarantine and no one without special accreditation was allowed in or out.

We hadn't expected quite so many though.

A woman walks through Kroo town slum in Freetown on August 13, 2014 (AFP Photo / Carl de Souza)

A woman walks through Kroo town slum in Freetown on August 13, 2014 (AFP Photo / Carl de Souza)We were stopped endlessly, interrogated and asked for our papers, checked for fever by men and women in white coats and generally treated like idiots travelling in the wrong direction.

I began to worry if maybe we were underestimating the danger.

Kailahun, an archetypal tropical rainforest town of baked mud and brick huts which has experienced the worst of the outbreak, finds itself described as one of the most deadly places on earth.

Among a population of 30,000 people, you'd be hard pushed to find anyone who hasn't been close to Ebola, which makes everyone the enemy.

A medical worker feeds an Ebola child victim at an MSF facility in Kailahun, on August 15, 2014 (AFP Photo / Carl de Souza)

A medical worker feeds an Ebola child victim at an MSF facility in Kailahun, on August 15, 2014 (AFP Photo / Carl de Souza)A gravedigger is offended when we won't let him ride in our car.

A drunk and perhaps mentally unstable old guy has to be shouted away as he lurches towards our (malfunctioning) open electric windows, letting go of several big hocks of snotty -- and possibly infected -- saliva.

I first thought about getting out of the hot zone when I was interviewing an articulate, animated man called Nallo, who seemed to be on the mend in the Medecins Sans Frontieres Ebola treatment centre in Kailahun.

We spoke for a few minutes across a buffer of perhaps two metres, separated by two waist-high orange plastic fences, and he told me how he planned to help end Ebola through education when he left the centre.

An MSF medical worker at an Ebola treatment facility in Kailahun, on August 14, 2014 (AFP Photo / Carl de Souza)

An MSF medical worker at an Ebola treatment facility in Kailahun, on August 14, 2014 (AFP Photo / Carl de Souza)A day earlier I had interviewed his wife Hawa, who was going home, Ebola-free, after being infected by her dying father-in-law.

Relieved at being given a second chance, she talked about how her heart remained in the MSF hospital, with Nallo.

I hope he made it.

Among the happy stories were the heartbreakers. One woman who looked to be in her 40s but was probably a lot younger (she didn't know) stared listlessly out from the centre's high risk area as nurses milled about and hygienists sprayed disinfectant.

She had lost her husband and seven-year-old son days before and seemed to be waiting impassively to follow them into the grave.

A member of Médecins sans Frontieres (MSF) holds a book recording details of the deaths of Ebola victims at the MSF facility in Kailahun, on August 14, 2014 (AFP Photo / Carl de Souza)

A member of Médecins sans Frontieres (MSF) holds a book recording details of the deaths of Ebola victims at the MSF facility in Kailahun, on August 14, 2014 (AFP Photo / Carl de Souza)Seventy-five miles down the road, Kenema is much worse.

At the centre of the city of almost 200,000 mainly Krio-speaking people, the embattled public hospital is chaotic.

A visitor or patient urinates against a wall just yards from the overstretched Ebola centre, where aid workers say 18 nurses have died (the hospital says 12).

Our hotel does excellent chicken fajitas but has no running water to speak of, let alone hot showers, and none of the chlorinated handwashing stations ubiquitous in Freetown and Kailahun.

People congratulated me on my bravery when I said I was going into the Ebola epicentre, like I was the star of an action movie deftly penetrating the lair of some unseen killer.

MSF medical workers carry the body bag of an Ebola victim in Kailahun, on August 14, 2014 (AFP Photo / Carl de Souza)

MSF medical workers carry the body bag of an Ebola victim in Kailahun, on August 14, 2014 (AFP Photo / Carl de Souza)The reality, of course, is somewhat more prosaic.

The idea is not to take risks, so you wash your hands until you can see your face in them and perfect the "that's close enough, mate - stay where you are" hand gesture.

In Kailahun and Kenema, Carl and Samir got some lovely images from the overcrowded marketplaces.

"There's no way I'm going in there. You kill yourselves if you want to, I'm staying out here," I would say, ever the risk-taking action hero.

Spending time in a hot zone isn't in itself a scary experience - it requires less bravery than climbing a tall ladder or removing a spider from a sink - but it does gnaw away at you.

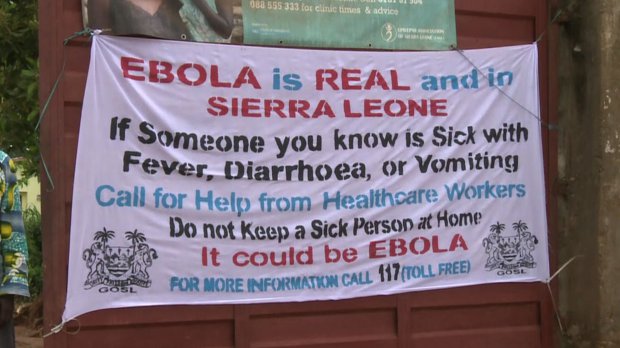

A sign warning of the dangers of ebola outside a hospital in Freetown on August 13, 2014 (AFP Photo / Carl de Souza)

A sign warning of the dangers of ebola outside a hospital in Freetown on August 13, 2014 (AFP Photo / Carl de Souza)A few days of touching nothing, fearing everyone, washing your hands and face every few minutes, and thinking any slight cough or rash is the start of haemorrhagic fever, brings its own stresses.

You can't try to put Ebola out of your mind, because you have to think about it every second or you could do something stupid and place yourself in danger.

Aid workers in eastern Sierra Leone say that when you stop fearing Ebola, it's time to go home.

Working on a big story is undeniably exciting but I was ready to leave by the time we got back to Freetown, to a stern hotel receptionist asking if we had washed our hands.

A girl suspected of being infected with the Ebola virus has her temperature checked at the government hospital in Kenema, Sierra Leone, on August 16, 2014 (AFP Photo / Carl de Souza)

A girl suspected of being infected with the Ebola virus has her temperature checked at the government hospital in Kenema, Sierra Leone, on August 16, 2014 (AFP Photo / Carl de Souza)It wasn't clear whether she meant in the last five minutes or during our entire time in the east. I reassured her that, either way, we had.

Getting home was an adventure in itself. We had to be rescued by a Sierra Leone army truck which literally shunted us out of danger after we got stuck several times in the deep, iron-rich mud of the jungle track out of Kailahun, with night drawing in.

With almost all airlines now staying clear of the Ebola zone, I had to scrounge a lift on a United Nations Humanitarian Air Service flight home.

Sierra Leone medical Clinical officers check on arriving passengers by taking their temperature on August 12, 2014 at Sierra Leone's International Airport, in Freetown (AFP Photo / Carl de Souza)

Sierra Leone medical Clinical officers check on arriving passengers by taking their temperature on August 12, 2014 at Sierra Leone's International Airport, in Freetown (AFP Photo / Carl de Souza)Twice we got refused landing permission by Senegal and were turned back to Guinea's capital Conakry, before I finally made it back to Dakar, where I live, on the third attempt.

People who contract Ebola can stay in the incubation period for anything up to three weeks - not knowing they are infected - before they crash.

My three weeks finishes on September 11, and I have been refusing every handshake by colleagues in the bureau. The upside is that I have also been excused the duty of washing up the lunchtime dishes or making coffee.

I have agreed with Samir and Carl that when September 11 comes, and the world is remembering another humanitarian disaster, we will connect via Skype and raise a glass to the victims of Ebola.

Viewing on a mobile device? Click here to open video in a new window.

Frankie Taggart is an AFP reporter based in Dakar.