Chasing bin Laden's ghost (and rabbits) in Pakistan

Paris - It was THE phone call with THE news I'd been waiting for for years. It was May 2, 2011 in Islamabad, and very early in the morning. I was in bed and half asleep. On the end of the line was Jennie Matthew, news editor in the bureau, as terse as usual: 'Washington is about to announce they've killed bin Laden in Pakistan.'

This was it. I'd been waiting for this day for six years, since reporting from Afghanistan in 2005. The question of what happened to Osama bin Laden, following his 2001 escape under US bombardment, coloured every NATO briefing. Many believed he was hiding across the border, in Pakistan's mountainous and semi-autonomous tribal belt, where the Americans didn't send ground troops, but instead waged their war from the sky, by drones.

An Afghan boy prays at the village of Zumrat near the Ama mountains where fighters for Osama bin Laden's network al-Qaeda and the Taliban are positioned, on March 4, 2002. (AFP / Jewel Samad)

An Afghan boy prays at the village of Zumrat near the Ama mountains where fighters for Osama bin Laden's network al-Qaeda and the Taliban are positioned, on March 4, 2002. (AFP / Jewel Samad)I rushed to my car, the reporter in me resigned to long days of hard toil in the bureau. It wasn't that the tribal belt was too dangerous for journalists, although they were. The problem was they were off-limits under punishment of jail or deportation at the hands of Pakistan's powerful military. So, I reasoned, it would be our correspondents on the ground who'd do all the reporting and gather all the images.

The bureau in Islamabad was buzzing with excitement. Everyone was arriving, even those who were supposed to be on holiday. We said hello and smiled at the thought of the world fixated on Pakistan.

We gathered around the bank of television screens to watch Barack Obama speak live from the White House and announce, as expected, the death of the founder of Al-Qaeda.

What came next astonished everyone. Obama said he was killed in Abbottabad. Abbottabad? The pleasant mountain town reputed for its middle-class life? The university town, the home to Pakistan's officers' academy, the 'Sandhurst' of Pakistan? For us reporters, it was a dream come true: the town was accessible to everyone, just 60 kilometres as the bird flies and by road, little more than two hours' drive.

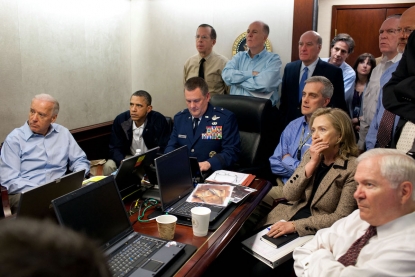

Official White House photograph made available on May 2, 2011 showing US President Barack Obama (2nd L), Vice-President Joe Biden, Defense Secretary Robert Gates (R) and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton (2nd R) in the Situation room as the operation unfolds (AFP / Pete Souza)

Official White House photograph made available on May 2, 2011 showing US President Barack Obama (2nd L), Vice-President Joe Biden, Defense Secretary Robert Gates (R) and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton (2nd R) in the Situation room as the operation unfolds (AFP / Pete Souza)Bureau chief, Emmanuel Giroud's brow furrowed at the thought of long days of coordination ahead. 'You'll go?' he said, turning to me. It was less a question and more a statement. 'With photo and video'.

We left immediately, photographer Aamir Qureshi, text journalist Sajjad Tarakzai, video reporter Mélanie Bois and myself. None of us returned home to pack a bag. On the road that snaked towards the mountains, we read everything that came out of Washington, the official narrative that quickly turned into the Hollywood movie 'Zero Dark Thirty'.

What we knew: bin Laden had been living with three wives, a dozen children and grandchildren, and two guards and their families. He was killed during a US Special Forces operation, his body taken away and buried at sea. Washington said Pakistan was not informed about the operation for fear of leaks. The country, especially its army, was widely suspected of colluding with jihadists.

A general view of Abbottabad on January 27, 2012 (AFP / Adnan Qureshi)

A general view of Abbottabad on January 27, 2012 (AFP / Adnan Qureshi)When we entered Abbottabad, other than the emerging foothills of the Himalayas, we were confronted by an entirely normal Pakistani scene: busy streets, low-slung homes, people dressed in traditional clothes. But there was a certain tension. Eyes lingered over vehicles coming in from out of town. That tension rose as we reached the neighbourhood of Bilal Town.

Our first impression was how agreeable it all looked: recently built homes, fields of vegetables, an impressive view of green hills. Then we passed five Pakistani army trucks carrying the remains of a helicopter. One of the US choppers had crashed into an outer wall of the bin Laden property, the only hiccup in an otherwise meticulously planned raid.

We whipped out our cameras, not knowing then that this would be one of the few pieces of concrete proof that the Americans had ever been.

(AFP / Str)

(AFP / Str)We quickly found the right place, a large building of white stone distinguished by its height - three storeys instead of the more normal two - and by two wide courtyards and high walls, stretching more than four metres, topped with barbed wire.

(AFP / Aamir Qureshi)

(AFP / Aamir Qureshi)When we got there, smoke was still spewing into the air, no doubt the rest of the stricken helicopter that the Americans disabled with grenade fire.

A military checkpoint stopped anyone from getting within 100 meters. Once we arrived, we moved fast, taking advantage of being the first foreign media at the scene. In a small neighbourhood market, people were happy to talk about the astonishing 45 minutes in the middle of the night that sowed fear in people's hearts and changed the dynamic of the town forever.

(AFP / Aamir Qureshi)

(AFP / Aamir Qureshi)The cacophony of the sudden arrival of helicopters, the shocking 'ball of fire' caused by the crash, explosions, gunfire, the screams of women and children. Then 30 minutes of silence, when the Americans confiscated documents and packed up bin Laden's body, before the fresh din of departure.

People in Bilal Town were worried. Their little oasis of peace was suddenly synonymous with terrorism. Would it become a new front in the 'war on terror'? They were shocked. They were angry. How could the Pakistani army sit back and let the Americans come and go with impunity?

Reporters Sajjad Tarakzai and Emmanuel Duparcq talking with neighbors, one year later (AFP)

Reporters Sajjad Tarakzai and Emmanuel Duparcq talking with neighbors, one year later (AFP)Others, even more suspicious, said the Pakistani army only arrived well over half-an-hour after the Americans had left, then told everyone to stay home. 'I struggle to believe it. It's more like a film, or a kind of game between the United States and Pakistan,' said one.

Within an hour of our arrival, coalesced the narrative that lasts to this day in Pakistan. National humiliation allowed few to believe Washington's version of events. Some said it was a stunt to embarrass Pakistan, they doubted bin Laden was ever there. Others claimed it was a deal between the Pakistani army and Washington, which each year spent billions on fighting Al-Qaeda and the Taliban. It was a present for Obama, some said, whom a year later called bin Laden's killing the "most important single day" of his presidency.

Supporters of hardline pro-Taliban party Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam-Nazaryati (JUI-N) shout anti-US slogans during a protest in Quetta (Pakistan) on May 2, 2011 after the killing of Osama Bin Laden (AFP / Banaras Khan)

Supporters of hardline pro-Taliban party Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam-Nazaryati (JUI-N) shout anti-US slogans during a protest in Quetta (Pakistan) on May 2, 2011 after the killing of Osama Bin Laden (AFP / Banaras Khan) People celebrate the announcement of the death of Osama Bin Laden at the White House in Washington DC, May 2 2011. (AFP / Chris Kleponis)

People celebrate the announcement of the death of Osama Bin Laden at the White House in Washington DC, May 2 2011. (AFP / Chris Kleponis)And deafening silence from the Pakistani military, arresting some of the neighbours and keeping journalists at arms' length, did nothing to quash conspiracy theories. Even police officers, sent to guard the house, couldn't believe that bin Laden was there. 'I don't believe it for a second, no one believes it,' said one officer. 'It's a joke!'

(AFP / Asif Hassan)

(AFP / Asif Hassan)Over the next two days, security forces allowed journalists, by then in the dozens, to approach the grey outer wall of the compound, but they never let us inside. People would saunter down after work to take photos. Hundreds soaked up the bucolic surroundings and enjoyed a Bilal Town sunset, until the army got fed up with all the tourists, and again sealed off the area with roadblocks.

(AFP / Asif Hassan)

(AFP / Asif Hassan) (AFP / Asif Hassan)

(AFP / Asif Hassan)Thanks to a contact, we stayed that night in a hotel that had only recently opened and was therefore little known. Most other foreign journalists opted to stay at the Pearl Continental, reputed for its comfort, but known also as a 'nest of spies'.

Jeux d'enfant à Abbottabad, le 7 mai 2011 (AFP / Aamir Qureshi)

Jeux d'enfant à Abbottabad, le 7 mai 2011 (AFP / Aamir Qureshi)During those early days, the intelligence services monitored the media before badgering them, little by little, into leaving town. At first, it was 'advice' or warnings such as text messages about 'four suicide bombers' ready to blow themselves up to avenge bin Laden. Then it became more insistent.

Our hotel, which had profited from an influx of guests, went above and beyond for the AFP team, which expanded and then swapped out journalists so they could rest. They gave us the run of the entire first floor, including the main sitting room, which we turned into our bureau. We quickly established a routine designed to foil security and get the best possible stories and images.

We left the hotel at 5:30am to arrive in Bilal Town by 6am, when the more professional soldiers relieved the police at the checkpoints. Aamir and Melanie would take as many images as possible.

(AFP / Aamir Qureshi)

(AFP / Aamir Qureshi)I worked with AFP text reporters Sajjad Tarakzai or Khurram Shahzad, as calm as they were resourceful. We'd saunter down the street blending in as Abbottabad residents, kitted out in baggy shirts, trousers and waistcoats, albeit with notebooks stuffed discreetly in our back pockets. When the police paid little attention and asked few questions, we got past the checkpoint. Otherwise, when they looked the other way, we'd try to duck and dive by hiding behind a car or walking through irrigation ditches. Hidden confidences of the neighbours would feed our dispatches in the morning; information from security forces in the evening.

For 10 days we reported on doubts that the complex had really housed bin Laden. Only the two Pakistani guards -- Arshad and Tariq -- had ever gone out, blending seamlessly with the rest of the population. If the size of the home raised eyebrows, the neighbourhood was well-off and well-guarded. No one had asked any questions.

We obtained video filmed by police inside the house, which refuted hasty claims about luxury living or high-tech security. On the contrary, any comfort was basic: grey-tiled floors, simple wooden cupboards and shelves, basic furniture. Security was literally the high walls and two lightly armed guards.

There was no internet, no mobile phones, no visitors. For six years, a strategy of stealth allowed bin Laden, apparently physically weakened, to evade the most powerful military in the world.

(AFP / Aamir Qureshi)

(AFP / Aamir Qureshi)After 10 days, we started running out of fresh material. The intelligence services, which thought the media circus had gone on long enough, ordered all foreign journalists left in Abbottabad to leave, threatening them with arrest or deportation. We too, packed up and left. Less than a year later, Pakistan destroyed the bin Laden compound and any secrets it still contained.

We too, packed up and left. Less than a year later, Pakistan destroyed the bin Laden compound and any secrets it still contained.

Young boys play cricket beside demolition works on the compound where Al-Qaeda chief Osama bin Laden was slain last year in the northwestern town of Abbottabad on February 26, 2012. (AFP / Aamir Qureshi)

Young boys play cricket beside demolition works on the compound where Al-Qaeda chief Osama bin Laden was slain last year in the northwestern town of Abbottabad on February 26, 2012. (AFP / Aamir Qureshi)One of our last reports explained how the Al-Qaeda leader lived, not just with three wives and a flock of children, but a hundred chickens, two cows and an indeterminate number of rabbits - a sort of 'little jihad in the prairie'. Solid investigative work, worthy of its geostrategic significance, allowed us to determine that Pakistani soldiers took the cows, and that the police shared out the chickens. Despite our best efforts, however, we never did find out what happened to bin Laden's rabbits.

The team, from left to right: Asif Hassan (Photo), Emmanuel Duparcq (text), Aamir Qureshi (photo), Khurram Shahzad (text),Masroor Gilani, Mélanie Bois (video) and Saadberg, the driver (AFP)

The team, from left to right: Asif Hassan (Photo), Emmanuel Duparcq (text), Aamir Qureshi (photo), Khurram Shahzad (text),Masroor Gilani, Mélanie Bois (video) and Saadberg, the driver (AFP)By Emmanuel Duparcq in Paris. Translation: Jennie Matthew. Editor: Michaëla Cancela-Kieffer