Writing history in Palmyra

Palmyra, Syria, April 1st, 2016 - My heart starts pounding faster and faster as the car speeds up. We’re barreling through the desert on our way to Palmyra, the ancient oasis city that had been ruled by the Islamic State group for nearly ten months.

That morning, my sources had confirmed the Syrian army’s full capture of the city and adjacent 2,000-year-old ruins. The news had spread to every inch of the world and AFP was about to be the first foreign media to report from Palmyra. I was brimming with pride and joy because I got to wake up the Syrian people on March 27, 2016, with news that so many people would be happy to hear. I am fielding phone calls from the Beirut bureau and from my Syrian friends who had fled to Germany, Norway, Lebanon, and Turkey. They all want to know, “How are the ruins?”

I am scared to find out.

As we approach, I can’t see much of the city besides a plume of black smoke that gives away the intensity of the battles that had happened there. A string of hills obstructs most of my view.

A road heavily damaged by shelling in Palmyra on March 29, 2016 (AFP)

A road heavily damaged by shelling in Palmyra on March 29, 2016 (AFP)I’m overwhelmed by a mix of feelings: joy, sadness, anxiety, and caution. Joy, because I will enter Palmyra and tell the world what happened there. Sadness, because I may publish potentially upsetting news about IS’s destruction of the ruins. Anxiety, because I was afraid to see what was left. All communication to the city had been cut off throughout the battles, and we didn’t know if IS had kept its word by detonating every last monument there.

Roadside bombs

And caution, because it would be my first time in a city where IS fighters used to roam the streets. I had heard about their fighting acumen, their kill in battle and in laying down dangerous roadside bombs.

But my emotions start to melt away as I prepare myself to work. I check the battery on my camera, my recorder, and my cellphone. I slip on my AFP hat, and I grab my notebook and pen to begin recording what I see. How would I write this story? How could I begin to tell the world what I’m seeing?

The remains of an ancient statue in Palmyra on March 31, 2016 (AFP / Joseph Eid - Beto Barata)

The remains of an ancient statue in Palmyra on March 31, 2016 (AFP / Joseph Eid - Beto Barata)We are a mere 500 meters away from the ruins. The first glimpse made my heart beat even faster. Is what I’m seeing real? Are there columns still standing? And the theatre and the citadel too? I could see some destruction here and there, but so much of what I thought would be turned to dust was still there.

"Can I get into the ruins?" I ask my army minder. He says it’s absolutely impossible: "The old city is completely mined, and it's very dangerous. We're in an area where Daesh used to be... Be very careful."

A ghost town in an old horror movie

Instead, we circle around to Palmyra’s residential neighbourhoods. It’s a ghost town -- it feels like I’m looking at scenes from an old horror movie. Fresh plumes of smoke are still snaking up from different spots around the city. Not a street had been spared. Cars lay in the middle of the streets, apartments sit empty with their doors still ajar. The neighbourhoods are completely destroyed and all I can hear is the howling of the wind and the distant explosions of roadside mines that cut through the silence every few minutes. The desert wind whips up the thick yellow dust.

As I tiptoe around apartment buildings, I peek in the craters left by artillery fire and clashes. I see no one. There are fresh signs of life: goods left in small corner shops, furniture in apartment homes. It was as if anyone just picked up and left. Nothing was left from IS except its black flags and some administrative papers.

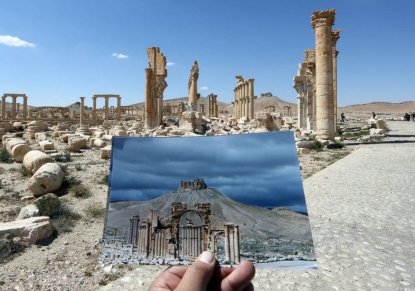

Palmyra's Arc of Triumph, in a picture taken on March 2014, and on March 31, 2016. The monument was destroyed by the Islamic State group in September 2015 (AFP / Joseph Eid)

Palmyra's Arc of Triumph, in a picture taken on March 2014, and on March 31, 2016. The monument was destroyed by the Islamic State group in September 2015 (AFP / Joseph Eid)I walk around the city carefully, watching where I step in fear of mines, trying to listen to my minder who is telling me where to go. I look around for someone, anyone, to tell me where I am exactly, what the name of the street is. "Is anybody here?" I call out. I hear nothing but the wail of the wind and the blasts of the mines.

Football and landmines

We finish our tour of the residential area and gather in the main square of the city. I try to send my pictures to our bureau, or call them to tell them I’m alright, but there’s no signal. As we wait for the army units to finish defusing the mines planted along the path to the old city, some soldiers begin playing with a football. Others take out out a drum and drink yerba mate. They take pictures to record this historic moment.

Finally, we are given permission to enter the ruins -- on the condition that we follow the army’s directions on where to walk so that we would not detonate any mines.

Destruction in Palmyra's museum on March 31, 2016 (AFP / Joseph Eid)

Destruction in Palmyra's museum on March 31, 2016 (AFP / Joseph Eid)As we enter, I tread slowly, testing the ground with my toes and trying not to rush so I can take in the sight of the towering monuments, smell the 2,000-year-old stones, feel the earth where thousands of battles, disasters, and armies of the world had fought had faded away. They were all gone, and this ground remains. History remains.

I pause to write in my notebook, snap a photo, and record some video footage. I stop so often that my colleagues get bored and leave me alone to do my work.

Walking through the ruins was a rollercoaster of emotions. Just as I begin to feel safe, with the fear of mines melting away, I hear a blast on the other side of the ruins. I am rigid again, and begin to walk carefully once more.

I break out into a grin when I see the famous Roman theatre, still standing upright. But my smile falls away when my eyes land on the Arch of Triumph, which was completely destroyed. I head towards what is left of the Temple of Bel, whose stones rest on top of one another on the hot earth under the noon sun. Sprouting among the stones were bright yellow flowers.

This is just the beginning. I see the funerary towers, which are partially demolished, and other columns that have been turned to rubble. But there were many columns still standing as witnesses to what had happened here.

Eventually, joy wins over sadness. I am reassured that the ruins are still alright, despite some destruction. I take a selfie, wearing my AFP hat and a smile. Later, when I have cellphone signal, I quickly post it on Twitter with the caption, "AFP in Palmyra."

#AFP IN #Palmyra.. Coming soon :) pic.twitter.com/ioB3VIdDeh

— Maher Al Mounes (@Maher_mon) 27 mars 2016

I used to boast to my friends that I visited Palmyra as a child, even though I couldn't remember much besides the general landscape, without any details.

Today, I am even prouder of my second visit to Palmyra. I am proud of myself, too, because I was the only correspondent from a foreign news agency on the ground in Palmyra. The pictures that I sent have circled the world.

I knew Palmyra was important in the history of civilization, but it also became important in the history of my own career, which is still in its early stages. I’m very happy that I could wrap up my first year with AFP with a news event as big as Palmyra. I wrote stories and sent eyewitness reports from the city that never tires. The fact that I was able to break this story has been a huge confidence boost for me, one that I’ve tucked away in my memory.

My visit to Palmyra ends as dusk begins. We pass the government checkpoint and I suddenly have cellphone service. From the car, I begin to send my very first words about this spectacular city. I receive a flood of messages from my colleagues -- Rim, Loay, and Youssef in Damascus, Rouba, Layal, Rana, Sammy, and Joseph from Beirut. They all want to know more, so I tell them everything I’ve seen.

When I return to Damascus from the city of Homs, my colleague Maya calls me from the Beirut bureau, telling me, “We are writing history.”

Maher al-Mounes is an AFP reporter based in Damascus. Follow him on Twitter (@Maher_mon). This post was translated from Arabic by Maya Gebeily in Beirut.

The Temple of Bel as it was on March 14, 2014, and the remains of the monument destroyed by the Islamic State group (AFP / Joseph Eid)

The Temple of Bel as it was on March 14, 2014, and the remains of the monument destroyed by the Islamic State group (AFP / Joseph Eid)