In Poland, conspiracies about a “Communist network” persist

WARSAW, March 30, 2016 - Lech Walesa, the former Polish president who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1983, may have worked for the country’s Soviet-era secret police, the dreaded and feared SB. That bombshell exploded in Poland in February as headlines of his possible involvement scrolled at the bottom of TV screens and were splashed all over newspaper front pages. You couldn’t turn on the radio without hearing about the allegations.

Walesa, whose leadership eventually wrested Poland from Communism, has denied being an informant for Bezpieka – the Polish slang name for secret police. But there is evidence showing Walesa did at least come into contact with the SB.

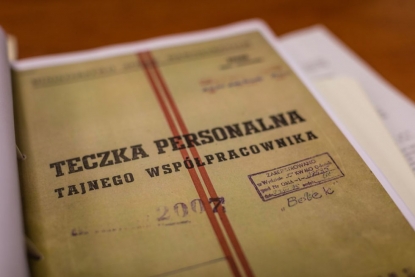

Investigators from the state-run National Remembrance Institute discovered numerous documents at the home of the former communist interior minister, the late General Czesław Kiszczak. The institute is tasked with investigating and exposing the crimes committed during Poland’s Nazi occupation and Communist past.

(AFP / Wojtek Radwanski)

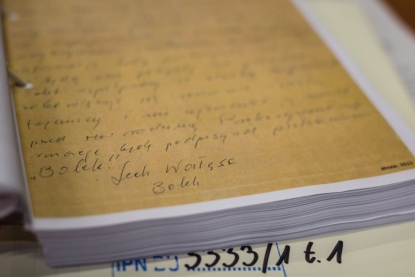

(AFP / Wojtek Radwanski)The documents investigators unearthed hint at Walesa’s possible involvement with Bezpieka. They found receipts signed by “Bolek,” what was Walesa’s code name, appearing next to his last name.

Various government officials claim this evidence indicates that, for 27 years, until just recently in fact, Poland was being run by the heirs and affiliates of the Soviet-era Communist regime -- in secret. These communists had supposedly obtained incriminating documents about legitimate government officials and had used them to blackmail these officials for years. Indeed, the communists had supposedly been pulling the strings behind the scenes all along.

Gift of fate

I’ve been a journalist for 40 years. I have seen my share of wars and dirty tricks. But still, I bore this news with a heavy heart.

I first met Walesa in 1981 at the Vatican during his first overseas trip to see “his pope” -- “our pope.” Recalling that I spoke Polish, the editor in chief at AFP pulled me from the foreign desk and sent me to cover the visit.

Strikers at the Lenin shipyards in Gdansk carry their leader Lech Walesa on August 30, 1980 (AFP / Lehtikuva)

Strikers at the Lenin shipyards in Gdansk carry their leader Lech Walesa on August 30, 1980 (AFP / Lehtikuva)Before the scheduled meeting with Pope Jean Paul II, I -- thanks to a mix of luck and arrogance -- was able to talk my way onto the bus carrying Walesa’s delegation. He impressed me. A simple man – he talked like a laborer from the country – he was visibly a little intimidated by everything happening to him. But what he said sounded right, very right.

Coming from the head of Solidarity, a workers’ union barely off the ground at the time, it opened a world of possibilities that would have been unthinkable in Poland just two years before. To me, Walesa was like a gift from heaven or a gift of fate. Someone who, for mysterious reasons, seemed to be incredibly lucky and special, who succeeded in everything he attempted.

Shopping in Rome with Ms Walesa

His wife was a former florist, beautiful, dignified, intelligent. When I got the chance to tag along, again by sheer luck, as she went shopping around Rome, that first impression of her stayed with me.

But less than a year later, Poland would be plunged into a circle of darkness. The Communist authorities would impose martial law. They would ban Solidarity. Walesa, along with other union leaders, was arrested and imprisoned. Their efforts to break him, however, through promises but also threats, handed out by Wojciech Jaruzelski’s men, would ultimately fail.

Polish policemen block the members of the outlawed Solidarity union during a rally on June 12, 1987 in Zaspa, near Gdansk (AFP / Dominique Faget)

Polish policemen block the members of the outlawed Solidarity union during a rally on June 12, 1987 in Zaspa, near Gdansk (AFP / Dominique Faget)Jaruzelski, the last leader of Communist Poland, was head of the United Workers’ Party. For the next decade, as Polish president, his intent to crush the Solidarity trade union for daring to challenge the Communist regime would terrorize an entire generation of Poles. Hundreds were arrested. Thousands fled.

For his part, Walesa refused to yield. He stayed true to the indomitable spirit of the Solidarity movement.

Keeping the Poles under the thumb

Denied a Polish visa, I could only watch the action from afar. The SB, unhinged, sought new ways to keep people under their thumb. When their efforts to inflict pain didn’t work, they promised money and even passports to make it easier for people to leave – anything to make people turn.

Some agents who took part in these campaigns were unmasked only after two decades, the painful shock of it blindsiding their families, their loved ones.

I headed to Poland in 1992, when I became the country’s AFP correspondent for six years. I saw Walesa again, then the country’s president. I had mixed feelings. He was surrounded by poor advisors. He was clumsy. Despite his good humor, his proposals were confusing. They lacked clarity. His spokesman would keep us after press conferences to explain what Walesa had meant to say.

But it didn’t matter. None of this detracted from what Walesa had accomplished. Well-respected intellectuals and famous artists like award-winning filmmaker Andrzej Wajda remained loyal to him. Poland, which had suffered under totalitarian rule for decades, was liberated through nonviolent revolution. The country immediately changed.

Not one drop of blood was shed, thanks in part to deals made with communists who ran some of the state’s essential structures – the army and the police. Moreover, the country had moved too far forward to go back, even under President Aleksander Kwasniewski, an ex-Communist, who took over in 1995. Kwasniewski had been turned onto Europe and to democracy. In 1999, Poland joined NATO. Five years later, it became part of the European Union.

Walesa, retired to Gdansk, a Northern city nestled on the Baltic Sea, remained an icon despite sometimes inflammatory and idealistic statements. He traipsed around the world, gave speeches… We started hearing rumors about his dealings with the SB. He responded vaguely, saying he “signed something” but didn’t take part in anything. Nothing came of it.

In the shadows, however, a conservative opposition relegated to the fringes of power by centrists and liberals, was left infuriated by the culture of impunity and the new wealth some ex-communists had accumulated. Members of this opposition were persuaded that a vast underground network of former Bezpieka agents was working to make sure they didn’t lose their privileged place in this new Poland.

Lech Walesa in Caracas, on February 19, 2016 (AFP / Federico Parra)

Lech Walesa in Caracas, on February 19, 2016 (AFP / Federico Parra)Before long, these opposition members started to question whether Communism itself had actually fallen: whether the fall of the Berlin War had been orchestrated by the communists themselves, under orders from the KGB, in order for them to save those parts that could be saved. And to extract billions from a believing and grateful West.

Those who could not manage to find their place in this new world, who regretted losing the security and a certain equality guaranteed under the former Communist regime, were tempted to believe in this conspiracy theory.

Conspiracy theories over a presidential air crash

Then, in 2010, tragedy struck, and the conspiracy took on new life. In April of that year, the aircraft carrying then-President Lech Kaczynski, his wife, and several key government and military figures crashed as it neared Smolensk in western Russia. All 96 people onboard died. Many people believed the crash was no accident.

The most extreme theory was that the Kremlin was behind the crash, although there was no proof. Another theory speculated that a plot was at work to cover up tragic mistakes by both the Poles and the Russians.

Soldiers carry the coffin of Polish President Lech Kaczynski during a farewell ceremony in Smolensk on April 11, 2010 (AFP / Andrey Smirnov)

Soldiers carry the coffin of Polish President Lech Kaczynski during a farewell ceremony in Smolensk on April 11, 2010 (AFP / Andrey Smirnov)Meanwhile, an entire body of work was born to substantiate some of the theories swirling around the crash. One conspiracy centered on a “network” of powerful hidden influences, an intricate spider web with invisible threads embedded inside government structures. One best-seller, “The Department’s Children,” mapped the ancestry of various influential journalists, particularly those of Gazeta Wyborcza, a p rominent leftist daily based in Warsaw, showing that their parents had ties to the Soviet-era secret police or to the higher echelon of the country’s old Communist party. The book also claimed that two of the most important private TV stations were set up by men from the same shadowy, Soviet-era world.

A hidden world of ex-secret agents

A novel by journalist Bronislaw Wildstein, a well-known anti-Communist, described modern-day Poland in similar terms. The book, “A Valley of Nothingness,” exposed a hidden world of ex-Bezpieka agents who were now successful in business and media while also retaining their hold on certain politicians and journalists.

To the people who believed in it, the discovery of documents bearing the codename “Bolek,” seemed to be solid confirmation of the conspiracy’s truthfulness. The findings, which covered a period of six years, included an agent contract with Bezpieka, a series of reports, and receipts for small amounts of zloty. The fact that this evidence was uncovered just as members of the right-wing Law and Justice Party, headed by Jaroslaw Kaczynski, were ascending to power put the conspiracy theories back in the spotlight. Jaroslaw Kaczynski, Lech Kaczynski’s twin brother, was a sworn enemy of Walesa.

Lech Walesa jokes with the Interior minister Czeslaw Kiszczak (left) and Father Alojzy Orszulik before attending the final session of talks between the Polish governement and the opposition, on April 5, 1989 in Warsaw (AFP)

Lech Walesa jokes with the Interior minister Czeslaw Kiszczak (left) and Father Alojzy Orszulik before attending the final session of talks between the Polish governement and the opposition, on April 5, 1989 in Warsaw (AFP)Foreign Affairs Minister Witold Waszczykowski started to insinuate that Walesa could have been a “puppet” for his intelligence officers. He made the case that Poland needed to investigate the decisions taken during the country’s liberalization and find out whether independence was the result of a national consciousness or whether it had been orchestrated by “certain internal or external special interests.”

Bad memories

The national public television station TVPInfo piled on by showing videos of interviews with a smiling Walesa next to Czeslaw Kiszczak, a Communist-era interior minister. The station played the images on a loop, a propaganda tool that did nothing but evoke bad memories.

However, the response from Walesa’s supporters – who organized widespread protests in Warsaw and Gdansk – amounted to just two words: “So what?”

In summary: yes, Walesa had contact with the SB. He may even have given them certain useful, actionable intelligence. But that should in no way outweigh the man’s historical significance.

The brouhaha dissipated somewhat after Walesa issued a denial, saying, “I have never betrayed anyone, nor accepted any money.” And continued to die down after the publication of a document meant to incriminate him, which showed Bezpieka severed its ties with him in 1976 due to his “arrogant attitude” and “unsatisfactory results.”

A 'declaration of cooperation' with the signature of Lech Walesa, aka 'Bolek', is shown to the media among other communist-era documents on February 22, 2016 in Warsaw (AFP / Wojtek Radwanski)

A 'declaration of cooperation' with the signature of Lech Walesa, aka 'Bolek', is shown to the media among other communist-era documents on February 22, 2016 in Warsaw (AFP / Wojtek Radwanski)But none of this stopped senior government officials, including current Polish President Andrzej Duda, from repeating that these documents “shed new light” on how Poland was governed for 27 years – a euphemism to accuse the previous liberal governments of having been enmeshed in the Soviet-era, Communist “network.”

This idea of a Communist “plot” or “network” seems extremely useful for the party in power – a tool it can use for multiple usages. Indeed, the Law and Justice Party has justified its opposition to the recent ruling of the country’s Constitutional Tribunal, which the party seeks to strip of power, for instance, by hinting that the decision was the result of “interests” from certain groups… Another unnamed plot – or the same – which extends to players abroad would explain the criticisms leveled by the European Commission or the Council of Europe against the party’s conservative members.

These rumors are sure to last, especially since they’re not completely woven out of whole cloth. Igor Janke, president of the Warsaw-based Freedom Institute, a conservative think-tank, told me that although he does not believe in the existence of a vast ex-Communist network, there could very well have been special local deals made by people with ties to the old regime to advance or defend their interests.

Emotions in Poland will remain high in the coming months. Case in point: when one of the tires on the presidential limo exploded, sending the car into a ditch (no one was hurt), a right-wing website suggested it was an attempted attack.

It remains to be seen whether the Poles’ fighting spirit is compatible with the country’s growing economy, for which Poles are extremely proud. And if Brussels, with its many varied concerns, will have the will and the means to tamp down their fervor.

Michel Viatteau is the AFP bureau chief in Warsaw. This blog post was translated by Solange Uwimana in Paris (read the original version in French).

Protesters hold Lech Walesa posters at an anti-government rally on February 28, 2016 in Gdansk (AFP / Janek Skarzynski)

Protesters hold Lech Walesa posters at an anti-government rally on February 28, 2016 in Gdansk (AFP / Janek Skarzynski)