Why AFP capitalises Black in North America – but not elsewhere

Following the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis in May 2020 and the subsequent protests against police brutality, there was widespread adoption in the US media of capitalised Black to refer to African Americans and other members of the African diaspora. That immediately raised the question of whether AFP, an international news agency based in Paris with a substantial editorial presence in North America, should do the same. Now, as Kamala Harris becomes the first woman and person of colour to hold the office of vice president, Stylebook editor Eric Wishart looks back at how the agency made its decision on the capitalisation of Black.

As a former editor-in-chief now responsible for special editorial projects, who wrote the ethics code and recently updated the AFP Stylebook, the responsibility fell to me to make a recommendation to the Agency’s news management. My first instinct was to propose that AFP join with other media in making the change globally – it made editorial sense and was appropriate given the social context and the renewed reckoning on race.

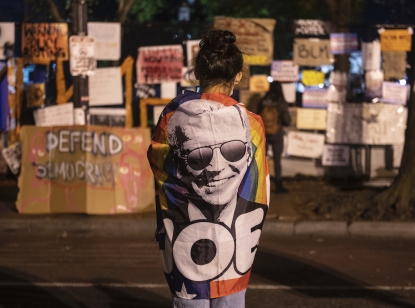

A woman wearing a Joe Biden flag looks at a wall of signs in Black Lives Matter Plaza near the White House, as people wait for election results, on November 6, 2020, in Washington, DC (AFP/ Andrew Caballero-Reynolds)

A woman wearing a Joe Biden flag looks at a wall of signs in Black Lives Matter Plaza near the White House, as people wait for election results, on November 6, 2020, in Washington, DC (AFP/ Andrew Caballero-Reynolds)In the United States, The National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ) issued a statement that it was important that the word is capitalised in “news coverage and reporting about Black people, Black communities, Black culture, Black institutions, etc.”.

“The organization believes it is important to capitalize ‘Black’ when referring to (and out of respect for) the Black diaspora”, and it also recommended capitalising colour when it was used to describe race, including White and Brown.

A black man and a white woman hold their hands up in a front of police officers in downtown Long Beach in New Zealand on May 31, 2020 during a protest against the death of George Floyd (AFP/ Apu Gomes)

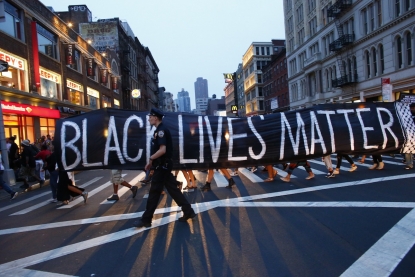

A black man and a white woman hold their hands up in a front of police officers in downtown Long Beach in New Zealand on May 31, 2020 during a protest against the death of George Floyd (AFP/ Apu Gomes)Major media quickly adopted the change including The Associated Press, Reuters, The New York Times, CNN, The Washington Post and Bloomberg. Capitalisation of black was seen as recognising the shared identity, history and culture of black people. Some news outlets adopted Black as their style for their worldwide coverage, including in Africa itself.

The message from the media in the United States, and also in Canada, was clear – black should be capitalised. But what about media in the rest of the world?

I took a two-pronged approach – seeing what other English-language media did outside of North America and consulting with AFP editors and bureaus to see what the feeling was on the ground, including, and crucially, in Africa itself.

Kamala Harris, flanked by husband Doug Emhoff, is sworn in as the 49th US Vice President by Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor on January 20, 2021, at the US Capitol in Washington, DC. (AFP / Brendan Smialowski)

Kamala Harris, flanked by husband Doug Emhoff, is sworn in as the 49th US Vice President by Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor on January 20, 2021, at the US Capitol in Washington, DC. (AFP / Brendan Smialowski)First, it became evident very quickly that few, if any, media outside of North America were adopting the change. In Britain, most media stayed with lowercase black, although some had, and still have, no consistent style and drifted between upper and lower case.

In other English-language media markets the style also remained lower case, although editors would usually keep the upper case “B” when using stories from news agencies that had made the change. So unlike other important changes in journalistic style there was no global adoption of capitalisation of black.

When it came to the internal consultation within AFP, there was an initial consensus in favour, although some of our staff felt it was a particularly North American issue. Others felt it was wrong to place members of an extremely diverse racial and ethnic population into what one staffer described as a “soup of blackness”.

Protesters with inscriptions painted on their chest reading "We All Are One" kneel as they raise their fists during a rally as part of the "Black Lives Matter" worldwide protests against racism and police brutality, at the Vieux-Port in Marseille on June 13, 2020 (AFP/ Clément Mahoudeau)

Protesters with inscriptions painted on their chest reading "We All Are One" kneel as they raise their fists during a rally as part of the "Black Lives Matter" worldwide protests against racism and police brutality, at the Vieux-Port in Marseille on June 13, 2020 (AFP/ Clément Mahoudeau) Democratic lawmakers take a knee to observe a moment of silence on Capitol Hill for George Floyd and other victims of police brutality June 8, 2020, in Washington, DC. (AFP / Brendan Smialowski)

Democratic lawmakers take a knee to observe a moment of silence on Capitol Hill for George Floyd and other victims of police brutality June 8, 2020, in Washington, DC. (AFP / Brendan Smialowski)There was also the question of white – while in North America there was unanimous adoption of capitalised Black, there was no consensus on white. Some news outlets adopted White, while others, the majority, kept it lower case. Their argument was that unlike in the case of black people, there were no shared racial, cultural or ethnic bonds that would justify capitalising white. And also, White could be seen as endorsing the language of white supremacists.

The replies from AFP’s African staff were decisive in the decision we would ultimately take – capitalising black made sense in a North American context, but could be a backward step elsewhere.

A protester shouts "Black Lives Matter" during a rain storm in front of Lafayette Park next to the White House, Washington, DC on June 5, 2020. (AFP/ Roberto Schmidt)

A protester shouts "Black Lives Matter" during a rain storm in front of Lafayette Park next to the White House, Washington, DC on June 5, 2020. (AFP/ Roberto Schmidt)Susan Njanji, deputy bureau chief in AFP’s Johannesburg bureau, said: “When the subject was broached and we were approached for comments, my gut reaction was ‘are we not joining the BLM activism bandwagon?’

“Then a few minutes later I thought ‘maybe it’s politically correct given the tension that engulfed the world after the death of George Floyd”. After speaking to her fellow staffers, there was a consensus that black should not be capitalised, or at least should not be singled out for capitalisation. “The feeling among colleagues was that ‘there are better ways to be sensitive to the black narrative’; ‘let’s not play to the gallery’; ‘black is not a title; it’s neither an ethnic group nor a nationality’.

Protesters holding placards run to join a demonstration in Centenary Square, central Birmingham on June 4, 2020, to show solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement in the wake of the killing of George Floyd (AFP / Oli Scarff)

Protesters holding placards run to join a demonstration in Centenary Square, central Birmingham on June 4, 2020, to show solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement in the wake of the killing of George Floyd (AFP / Oli Scarff)“We have to be careful that capitalising B is not be seen as an act of advocacy. If we choose to do so, let it be uniform across all races. That could look quite busy in our copy. I’m black and having my race capitalised does not make me feel special, but discriminated.”

In Mogadishu, AFP correspondent Mustafa Haji Abdinur said: “For most Somalis in Somalia including myself, Black Lives Matter is an issue of America and the Americans.

“Of course, racism must be discouraged but blacks in Africa are not directly concerned about the specific issue. And if you would refer to Black as culture, the question is do we all black Africans share common culture? The answer is simply NO. To me, Black is simply not different than White in being a colour”.

Alexis kneels with his baby at a protest in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement in Dakar on June 9, 2020 (AFP / John Wessels)

Alexis kneels with his baby at a protest in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement in Dakar on June 9, 2020 (AFP / John Wessels)

Other reactions from AFP’s African staff included:

“ I am black, but I have a different culture from black people elsewhere - be it in the West or in Africa. I strongly feel that referring to Black as a culture will, in the long run, build and embolden general stereotypes about Africans”.

“You have people of entirely different cultures, who look different, who speak many, many different languages. Getting foreign readers to see that ‘Africa is not a country’ is an important part of our daily work, and lumping the struggles of black people here, with those of black people in America or elsewhere, would be a step backward, a step towards further erasing the diversity of black people and of Africans in particular”.

“I still see no justification of capital B for blacks and not capital W for whites, if the argument is the said ‘shared culture or shared experience’”.

“I believe it is very much an American issue and the danger is that the power of social media has created an echo chamber in which there is pressure to conform rather than critically looking at an issue or looking at it from a truly international perspective”.

(AFP / Chandan Khanna)

(AFP / Chandan Khanna) (AFP / Chandan Khanna)

(AFP / Chandan Khanna)“There are more than one billion people in Africa, whose day to day existence is not shaped by the colour of their skin or any of the same challenges of black people in the US”.

The conclusion -- while capitalising black was the right thing to do in North America, it could be counter-productive elsewhere. In particular, it was seen as wrong to define the majority of people on the African continent, with their vast racial, cultural and ethnic diversity, with the generic term of capitalised black.

Based on that, the decision by AFP was to join other media in capitalising black as an alternative to African American and as a racial, ethnic and cultural identifier in North America, but keep black lower case elsewhere.

A police officer patrols during a protest in support of the Black lives matter movement in New York on July 09, 2016. (AFP / Kena Betancur)

A police officer patrols during a protest in support of the Black lives matter movement in New York on July 09, 2016. (AFP / Kena Betancur)White would remain lower case while brown, which is used in reference to people of unrelated racial and ethnic backgrounds around the globe based on their skin colour, would continue to only be used in direct quotes.

The new style rule was introduced on September 24 and here is the entry in the Stylebook entry section on coverage of Race:

In North America, capitalise Black as an alternative to African American and when using black as a racial, ethnic and cultural identifier e.g. Barack Obama was the first Black president of the United States. Use lower case black as a racial identifier elsewhere. Black should be used an adjective and not as a noun – Black/black people, not Blacks/blacks. White remains lower case. Brown should only be used in quotes.

Yes, it does mean AFP has two styles, but the Agency has long used both “British” English and “American” English terms, so that in itself is nothing new. The Agency will continue to monitor how references to race and other sensitive issues develop and make the necessary adjustments when appropriate.

As language evolves, so does the AFP Stylebook.