When words lose meaning

San Juan -- If you use words too much, they begin to lose their meaning. After you write and read “devastated” and “destroyed” hundreds of times, the effect begins to wear off.

So how to explain the magnitude of the destruction in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria destroyed swathes of the US territory home to 3.4 million souls? You can read that most of the power went out on September 20, but do you realize how exactly that affects the people living there?

AFP had a team of reporters, photographers and video journalists covering the disaster. Some were used to documenting calamities, others arrived and got stuck on the island when calamity struck back home. Here Leila Macor, Ricardo Arduengo, Jose Osorio, Hector Retamal and Eleonore Sens recount how they kept going to bear witness to the worst natural disaster to hit the island in a century.

A man rides his bicycle through a damaged road in Toa Alta, west of San Juan, Puerto Rico, on September 24, 2017 following the passage of Hurricane Maria.

(AFP / Ricardo Arduengo)

A man rides his bicycle through a damaged road in Toa Alta, west of San Juan, Puerto Rico, on September 24, 2017 following the passage of Hurricane Maria.

(AFP / Ricardo Arduengo)Working in the dark

Leila Macor, journalist based in Miami

When Maria hit Puerto Rico, it sent the island back to the Middle Ages -- no power, no clean water, no gas, no telephones, no Internet. The AFP team was sent back to the dark ages of journalism as well.

We had a satellite emergency telephone and two satellite internet terminals, with which we could transmit, but not monitor the news as we would normally do on such a story. An elementary trick of the trade -- confirming something -- became an odyssey. Usually to know if a rumor was true, you’d make a few phone calls. Now the only way to find out was to go to a town and ask the residents if they had seen their mayor pass by.

A man walks on a highway divider while carrying his bicycle in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria in San Juan, Puerto Rico, Thursday, September 21, 2017.

(AFP / Ricardo Arduengo)

A man walks on a highway divider while carrying his bicycle in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria in San Juan, Puerto Rico, Thursday, September 21, 2017.

(AFP / Ricardo Arduengo)We worked in the dark most of the time, without seeing the big picture until night came and we connected to the internet at the government press center in San Juan. There we would learn that US President Donald Trump said during the day that the reporters on the ground were exaggerating.

What an impotent feeling, to realize that all that we had seen and transmitted during the day in this US territory was falling on the deaf ears of the American president.

Solar panel debris is seen scattered in a solar panel field in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria in Humacao, Puerto Rico on October 2, 2017.

(AFP / Ricardo Arduengo)

Solar panel debris is seen scattered in a solar panel field in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria in Humacao, Puerto Rico on October 2, 2017.

(AFP / Ricardo Arduengo) Iris Vazquez washes clothing at an open road drainage next to a road in Corozal, west of San Juan, Puerto Rico, on September 24, 2017 following the passage of Hurricane Maria. (AFP / Ricardo Arduengo)

Iris Vazquez washes clothing at an open road drainage next to a road in Corozal, west of San Juan, Puerto Rico, on September 24, 2017 following the passage of Hurricane Maria. (AFP / Ricardo Arduengo)

After the hurricane, people living here had nowhere to go. Hospitals did not work. There was nothing open. No one could be called. Each resident was -- and many still are -- alone, in his house or what remained of it, healthy or injured, in a small personal universe in which the days were spent looking for something to eat, something to drink, a place to bathe.

Help was excruciatingly slow in coming. After a week, the people living in villages in the interior of the island would welcome us, hoping we were the Red Cross or US federal emergency personnel. “We are journalists,” we would tell them. “The only thing we can do is tell your story.”

Wilson Hernandez and his family rebuild their house destroyed by Hurricane Maria in the neigborhood of Acerolas in Toa Alto, Puerto Rico, on September 26, 2017.

(AFP / Hector Retamal)

Wilson Hernandez and his family rebuild their house destroyed by Hurricane Maria in the neigborhood of Acerolas in Toa Alto, Puerto Rico, on September 26, 2017.

(AFP / Hector Retamal)We were always welcomed. The people were angry with the government and understood that the only way to hope to get help was to talk to reporters. And so they opened the doors of what remained of their homes to show the damage inside. As we listened to their stories, we struggled not to cry. And we invariably hugged them when we left.

I suppose that’s why that most of my text stories, like the photos and videos of my colleagues, were portraits of the victims.

A man walks past a house laying in flood water in Catano town, in Juana Matos, Puerto Rico, on September 21, 2017.

(AFP / Hector Retamal)

A man walks past a house laying in flood water in Catano town, in Juana Matos, Puerto Rico, on September 21, 2017.

(AFP / Hector Retamal)Disaster hitting home

Ricardo Arduengo, photographer based in Puerto Rico

Living in Puerto Rico, I have quite a bit of experience in covering natural disasters in the region. I was there for Hurricane Irene in the Dominican Republic in 2011 and the Haiti earthquake in 2010. But this was like nothing I’ve ever seen before.

For one thing, the destruction hit home. Literally. Neighbors and friends were affected. My family’s home is in Barranquita, in the center of the island and it took me three days before I could go there to check up on them. They were lucky, they only had broken branches and one window broken.

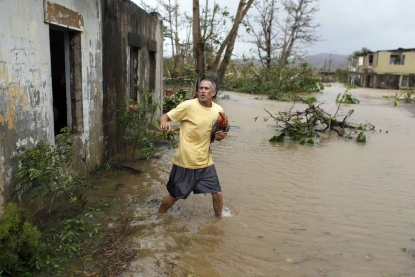

A man rescues a rooster from his flooded garage as Hurricane Maria hits Puerto Rico in Fajardo, on September 20, 2017.

(AFP / Ricardo Arduengo)

A man rescues a rooster from his flooded garage as Hurricane Maria hits Puerto Rico in Fajardo, on September 20, 2017.

(AFP / Ricardo Arduengo)But even though this story was personal, I kept telling myself that it was still a story and I had to keep working as I would on any other disaster anywhere else. You have to show the story, you have to keep going. So I try to block things out. I keep doing my work. Because if I let it get to me, it’s going to affect my job. And my responsibility is to show what is happening.

I found that the most effective way of conveying the scope of the disaster was with aerial photos. They gave a great sense of the scale of the destruction. But I complemented them with photos from below. So almost all of the photos that I took with a drone I also took from the ground.

An aerial view shows the flooded neighbourhood of Juana Matos in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria in Catano, Puerto Rico, on September 22, 2017.

(AFP / Ricardo Arduengo)

An aerial view shows the flooded neighbourhood of Juana Matos in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria in Catano, Puerto Rico, on September 22, 2017.

(AFP / Ricardo Arduengo)Covering a disaster when calamity hits home

Jose Osorio, video journalist based in Mexico City

I was getting ready to cover the anniversary of the deadly 1985 earthquake that killed thousands in Mexico in 1985 when my editors called, asking me to go to Puerto Rico to cover Maria, which was about to bear down on the island.

I arrived on September 19, just before the airport closed. I headed to the village of Fajardo, where I was going to wait out the storm with Ricardo Arduengo. I stopped at a gas station to film people lining up to fill up their gas tanks, when my girlfriend called. The ground is shaking in Mexico City, she said nervously.

I tried to calm her, saying that it was probably just a tremor. But it turned out that it wasn’t. A 7.1-magnitude quake just shook the Mexican capital, killing more than 360 people people and leaving thousands homeless.

I was torn. On the one hand, I had to hurry to Fajardo because Maria was due to make landfall in just a few hours. But I wanted to go back home to my family and friends, both to be with them and to cover the tragedy that struck. It took me more than a day to find out that all of my loved ones were well, but that the building in which I lived was damaged and my father’s building was damaged so much that it was no longer habitable.

As I worked the first few days, I was hoping to return home quickly. But that hope faded as the extent of the damage from Maria became clear and the airport remained closed. When we left Fajardo, I really saw just how severe the damage was. There were hundreds of fallen trees and poles on the roads, the streets were mostly flooded and deserted. Whenever I crossed a flooded area my heart sank a bit, hoping the rented truck would not get stuck.

I reconciled myself with having to be away from home for a while and covered this other natural disaster as best as I could. I eventually got home a week later.

The only thing to do

Hector Retamal, photographer based in Haiti

I have been based in Haiti for four years and last year covered Hurricane Matthew. When you cover natural disasters, you see lots of pain, which obviously affects you. But you have to process these feelings. I try to channel all that energy into my photos.

In the days following Hurricane Maria, I tried to show how people were affected by the storm -- the destroyed houses, the people looking for drinkable water, women cooking at night outside the ruins of their homes.

Maria prepares food during nightfall next to her home, destroyed by Hurricane Maria, in Toa Alta, Puerto Rico, on September 25, 2017.

(AFP / Hector Retamal)

Maria prepares food during nightfall next to her home, destroyed by Hurricane Maria, in Toa Alta, Puerto Rico, on September 25, 2017.

(AFP / Hector Retamal)As the days went by, I tried to look for stories to show how the people were overcoming the difficulties, despite losing everything. This is one of the reasons that I like the image of the young man with a flag that says "I'm rooting for Puerto Rico", because for me it symbolizes strength and hope after the destruction.

(AFP / Hector Retamal)

(AFP / Hector Retamal)A few days before returning to Port-au-Prince, I visited the people I had photographed in the days immediately following the hurricane. It was my way of trying to get close to them.

We must be close, not only to have good images, but because of respect. It doesn’t make sense to me to go somewhere to take pictures and then not know what happened to those people aftewards, not to show an interest in their stories and their lives. That’s why I wanted to see them again before I left. I wanted them to feel that someone cared about their pain.

Gloria Lynn cries next to a salon that was flooded after the rains related to the passage of Hurricane Maria, in Toa Baja, Puerto Rico, on September 22, 2017.

(AFP / Hector Retamal)

Gloria Lynn cries next to a salon that was flooded after the rains related to the passage of Hurricane Maria, in Toa Baja, Puerto Rico, on September 22, 2017.

(AFP / Hector Retamal)The responsibility of bearing witness

Eleonore Sens, video journalist based in Washington DC

For the first time in my professional career, I really felt the responsibility that journalists have to bear witness. As the US president feuded with the mayor of San Juan over the quality of aid provided to the island, my colleagues and I were bearing witness to a natural and humanitarian catastrophe.

The further from San Juan you got, the worse the conditions became. People drank water from the river; many couldn’t even get in touch with family to let them know they were alive. More than 10 days after the disaster, there was still no sign of any aid in the villages inland.

What struck me was the resilience and resourcefulness of Puerto Ricans faced with such deplorable conditions. Instead of complaining that they weren’t receiving aid, residents organised themselves to help each other.

The tenacity of the human spirit sometimes almost made me forget the urgency of the situation. People smiled at us and thanked us for documenting their plight. And then reality would come roaring back in. I remember meeting one little girl and her mother who were living between boards after their house was destroyed. They had received zero aid from anyone. The conditions they were living in were truly shocking.

This blog was written with Yana Dlugy in Paris.