When a 'workquake' strikes home

Mexico City -- It all started with an earthquake on September 7, just before midnight.

It was the first one my family and I had experienced, but when the whole building started to shake, it didn't take long to realize what it was.

Since we arrived for my posting in Mexico in May, people had warned us over and over. Mexico sits on top of five tectonic plates, and earthquakes are a fact of life here.

It's impossible to live through those endless seconds of shaking without contemplating the possibility that your home could come down on top of you. Standing there like an idiot, my baby in my arms -- I didn't realize we were supposed to crouch in a protective position next to a load-bearing column -- I wondered what it would be like if our eight-story building collapsed with us -- me, my wife Celia, our two-year-old daughter and eight-month-old son -- inside.

But soon enough that faded to the background.

After the shaking stopped, there was business to take care of.

First, get the baby back to sleep.

Then, calm my daughter, who's just learning to talk and wanted words for the gaping crack that had opened in our living room wall. I tried my best to explain. She pointed to the cracked plaster: "Workquake!" she marveled.

That turned out to be fitting, because the next thing I learned about earthquakes is that they are a hell of a lot of work.

Once we got the kids back to bed and asked the neighbors if we should be worried about the cracks in our walls -- just a flesh wound, they said -- I dove into a long night of reporting, writing and coordinating that lasted through the next day.

The real damage, it turned out, was in the south. Mexico City had been spared the worst. We sent reporting teams to the disaster zones. After a while, life went on.

Relaxing at a fountain at the Revolution Monument in Mexico City, April 6, 2017.

(AFP / Ronaldo Schemidt)

Relaxing at a fountain at the Revolution Monument in Mexico City, April 6, 2017.

(AFP / Ronaldo Schemidt)And so, we're nonchalant when September 19 rolls around -- the anniversary of a 1985 quake that killed more than 10,000 people in Mexico, and the occasion for annual earthquake drills.

At AFP, we rehearse our routine with knowing smiles. We've just been through this for real.

When the alarm goes off at 11:00 am, we grab the backpack with our satellite phone and BGAN terminal. We calmly file out to our meeting point, a fountain nearby. We test the internet connection and call our regional headquarters in Montevideo on the sat phone. Check, check, check.

It's a bright, sunny day. The mood is laid-back as office workers line up behind shiny signs directing them to their meeting points.

Eventually, everyone trickles back to work.

Smiling through the drill.

(AFP / Pedro Pardo)

Smiling through the drill.

(AFP / Pedro Pardo)I'm sitting at my desk a couple hours later when my chair starts to vibrate. A passing truck, I think. Except it seems to be one giant mother of a truck. Before I can even form the thought, the alarm goes off: "Alerta sísmica!"

This time, total panic.

I start toward the door, then decide to go back for my notebook. I'm even about to go back around the desk and send a quick note to my editors when the shaking gets really serious and convinces me that's a spectacularly stupid idea.

The shaking is violent. Several colleagues nearly fall going down the stairs of the old house where we have our office.

The door to the street keeps banging shut, so I hold it open for a few people before deciding that that, too, is pretty stupid.

Walking to the fountain is like trying to cross a trampoline with someone bouncing on it. The ground refuses to hold still.

Once there, you can tell it's bad. A building under construction on the north side of the plaza is shaking ominously behind its black protective tarp. People's faces are contorted with emotion. Many are crying.

Reaction to the real earthquake, after the drill. (AFP / Ronaldo Schemidt)

Reaction to the real earthquake, after the drill. (AFP / Ronaldo Schemidt)"It's the same nightmare as 1985," sobs one woman -- the first quote brought back by crack reporter Yemeli Ortega.

Yemeli and I try to call Montevideo, but the phone networks are already jammed. I can’t get a call through to my wife. The backpack with the sat phone is nowhere to be found. I desperately write a WhatsApp message to Nina Negron, head of the Spanish desk in Montevideo.

"Nina, alert: Powerful earthquake shakes Mexico City."

The message sits there for an eternity -- and then goes through. We have a link to the outside world -- and each other. WhatsApp will prove to be a crucial tool to communicate and coordinate our coverage over the next two weeks.

It also works to send videos to Montevideo. Sloooooowly. But it works -- a crucial save, since one of our regular video journalists is in Puerto Rico to cover Hurricane Maria and the other is on vacation in the Norwegian fjords.

About 15 of us meet up on the plaza. Two-person teams of photographers and reporters start heading out to the sites where WhatsApp messages tell us bad things are happening: collapsed buildings, trapped people, gas leaks, explosions. I start to lose track of who's where and begin jotting it down in my notebook. Pedro Pardo and Yussel Gonzalez: gas leaks. Jennifer Gonzalez and Omar Torres: collapsed building.

AFP’s Mexico City office is in the heart of La Roma, one of the neighborhoods that, as we learn later, was hardest hit.

Normally a hipster playground of trendy restaurants, bars and boutiques, Roma now looks like something out of a post-apocalyptic movie.

Buildings collapse into mangled piles of steel and concrete. Crowds swarm onto the rubble, frantically trying to reach people trapped inside. Ambulances struggle to part the sea of gridlocked cars and shell-shocked pedestrians. Lots of people clearly aren’t going to make it out alive.

Donaciano Davila, our technician, finally arrives with the magic backpack. He'd been charging the batteries upstairs.

We connect a laptop and I start emailing Montevideo the flurry of information coming in on WhatsApp -- the raw material used by the regional desk to write our first stories.

A building in one of Mexico City's most fashionable neighborhoods after the quake.

(AFP / Pedro Pardo)

A building in one of Mexico City's most fashionable neighborhoods after the quake.

(AFP / Pedro Pardo)Almost as soon as I leave our quivering office and get to work on the street, I get that sickening-sweet adrenaline rush that -- I hate to admit -- always comes with covering these kinds of events: a mix of pride in bringing an important story to the world and, just beneath, shame that it's due to other people's suffering.

But karma has a few tricks in store for me and my guilty conscience.

As I type away on the plaza, I get the first message from my wife, who was at home with the baby in La Condesa, the neighborhood next door, when the quake struck.

"Are you there??? It was horrible. Send me news."

The aftermath. (AFP / Ronaldo Schemidt)

The aftermath. (AFP / Ronaldo Schemidt)I manage to get a patchy call through on WhatsApp. The apartment was badly damaged. It's too dangerous to go back. She's on the street with the baby. Her battery is about to die. Come quick.

I scrawl her location in my notebook, too.

A message arrives from my daughter's preschool in San Miguel Chapultepec, the neighborhood next to ours. All the children are fine, but shaken. Please come get them asap.

Talk about trouble balancing work and family life. How do you cover an earthquake and take care of your family when you are among its victims?

I fire off one last email to Montevideo -- buildings collapsed, people trapped, chaos on the streets -- and tell my boss, bureau chief Sylvain Estibal, I have to go find my family. He wishes me luck and tells me we're welcome to stay at his place. He may live to regret that.

The city is an eerie mix of clogged and empty streets. Crossing Roma, I walk through shattered glass and chunks of fallen concrete and am surprised no one has cordoned off the sidewalk -- before I realize there is no one to cordon off the sidewalk, and start walking up the middle of the street instead. Arriving at Parque España, traffic is hopelessly gridlocked, a maze of perpendicular cars at the northern intersection.

(AFP / Pedro Pardo)

(AFP / Pedro Pardo)This park and nearby Parque México are the reason my wife and I settled in Condesa: impossibly lush splashes at the heart of the smoggy city that look like something the French landscape-architecture genius Andre Le Notre would have created if Louis XIV had given him a jungle to work with instead of Versailles.

Now, walking on the edge of the park is like moving through a bad dream. The sidewalks are deserted. Cracks run down the facades of fancy buildings. It smells of gas.

Halfway up the park, I see a huge crowd and head toward it. They are gathered around a collapsed apartment building on Amsterdam Avenue, one of the most chic addresses in the city. The pile of rubble is a hive of activity. People are working furiously to remove the large pieces of concrete. My attention fixes on a man in a white shirt and dark tie, perched on the rubble alongside other civilian volunteers and Civil Protection officials in helmets and neon vests. That man seems to sum up everything about the moment: the violent interruption of whatever we were all doing before; Mexicans' heroic yet dangerous impulse to throw themselves into the rubble.

That is a legacy of the 1985 quake, when the government was so overwhelmed that people had little choice but to take matters into their own hands.

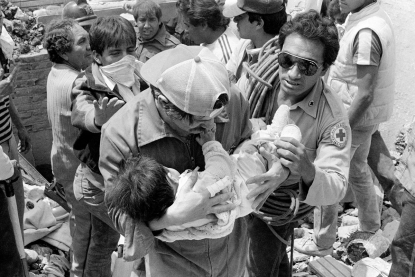

Rescuers evacuate a wounded child from the Regis Hotel in Mexico City after an earthquake on September 19, 1985, which killed up to 30,000 people. (AFP / Omar Torres)

Rescuers evacuate a wounded child from the Regis Hotel in Mexico City after an earthquake on September 19, 1985, which killed up to 30,000 people. (AFP / Omar Torres) People remove debris after the earthquake on September 19, 2017.

(AFP / Alfredo Estrella)

People remove debris after the earthquake on September 19, 2017.

(AFP / Alfredo Estrella)

I shoot three short videos of the scene with my iPhone, focusing mainly on the man in the tie, and send them to Montevideo via WhatsApp. Like most of us in the office, I have next to no professional video experience. But we've been trained to use our phones for just such emergencies. Our images will be among the most watched news in the world that day.

I linger long enough to get some details from an ambulance crew -- five people trapped inside -- and continue my journey, watching my phone the whole way to check the progress of my video transfer and my dwindling battery.

I find my wife three blocks from our apartment. I'm surprised to see she has an entire entourage: the baby, her friend Mag, who is visiting from France, plus our babysitter, the cleaning lady and the handyman who had just finished fixing the walls damaged by the previous quake. They have their own families to worry about, but didn't want to leave my wife and baby until I arrived.

Oddly enough, they're all laughing at a joke. It turns out my wife had been complaining to the handyman, Señor Armando, that there was a slight imperfection in the living room wall. "When the light hits the plaster, you can see it's uneven." Then the earthquake came along and smashed the entire thing to bits.

Señor Armando is imitating my wife, to unanimous hilarity: "Oh look, there's a slight imperfection," he says, his eyes alight.

The wall where the imperfection used to be. (Photo courtesy of Joshua Howat Berger)

The wall where the imperfection used to be. (Photo courtesy of Joshua Howat Berger)We give the babysitter and cleaning lady some money -- their bags are stuck upstairs, with all their money and IDs -- and send them on their way.

Señor Armando helps us find the road to our daughter's school, which we've never done on foot, then goes his own way.

We stop at a big-box store that is a bizarre oasis of normality and buy food, water and a cell phone charger.

The French school my daughter attends (my wife is French) is an oasis, too. The teachers have somehow arranged a splendid picnic in the courtyard. Children are playing on the swings. Parents are chatting. It's all very cozy and French, and we want nothing more than to stay.

I look at my wife. "This is bigger than just us," I say. "I have to go back to work." She nods her unenthusiastic agreement.

We accept some food, put our daughter in her stroller and venture back into the disaster zone.

Looking for survivors. (AFP / Ronaldo Schemidt)

Looking for survivors. (AFP / Ronaldo Schemidt) Remains of a life. (AFP / Alfredo Estrella)

Remains of a life. (AFP / Alfredo Estrella)

It takes us maybe two hours to walk the three kilometers back to AFP, when you factor in stops to nurse the baby, change diapers and decide the safest route.

The last stretch takes us past one of the worst collapse sites, a seven-story office building where 49 people died.

It is a mountain of wreckage, with rescuers climbing all over it. Just looking at it, you know the odds are grim for anyone inside.

I can only hope my kids' little brains don't register the scene.

Looking for survivors day after the quake. (AFP / Yuri Cortez)

Looking for survivors day after the quake. (AFP / Yuri Cortez)We arrive back at the fountain, but it has been turned into a humanitarian camp, covered in plastic tarps and already brimming with donated food aid.

My colleagues are nowhere to be seen.

It turns out the authorities told us we couldn't use our generator there because of gas leaks. So we went to Plan C: the Office Max parking lot up the street.

With my son strapped to my chest in a baby carrier, I grab a laptop and get back to work.

The bureau moves outside. (Photo courtesy of Joshua Howat Berger)

The bureau moves outside. (Photo courtesy of Joshua Howat Berger) The author multi-tasks. (AFP / Pedro Pardo)

The author multi-tasks. (AFP / Pedro Pardo)

For the first time, I have a chance to read the stories the desk has been writing all day. They've done a fantastic job assembling the material we've been sending. But nothing can replace a first-hand account. I grab the story and start adding what I've seen and felt: the shock of the earthquake improbably striking two hours after the drill; the sight of some of the city's most vibrant neighborhoods reduced to wastelands; the smell of gas leaks everywhere; the man in the tie.

Sylvain, the photographers and Ingrid Tello, our administrative mastermind, are meanwhile deep in the logistics of covering the quickly evolving disaster scenes. Traffic is so backed up the only way to get anywhere is on motorcycles. So our receptionist, Ricardo Zamorano, enlists his three sons, all bikers, to work through the night shuttling our team around: a school where 19 children were killed; a factory that was flattened. We keep our base camp running until about midnight. Meanwhile, my wife and Mag somehow manage to feed the kids and keep them more or less content despite the fact it is way past their bedtime. Finally we decide to pack up and work the rest of the night from home. Those of us whose homes were damaged go to Sylvain's, in the relatively stable neighborhood of Polanco.

Even there, the quake gave things a good shake. We arrive at his apartment to find various objects thrown to the floor, including a heavy gold statuette. It's a Cesar, the French equivalent of the Oscar, which my ridiculously talented boss won for directing the film "When Pigs Have Wings." If an earthquake has to toss your stuff around, you should at least do it in style.

Sylvain hosts nine of us that night, sleeping wherever we can if at all. Our family of four, plus Mag -- who is surely having the worst vacation of her life -- get the two guest bedrooms, one kid in each.

Over the next few days, I keep adding to the guest list. The babysitter comes. The cleaning lady. I go back to our broken, debris-strewn apartment to salvage some belongings and find our cat, who we thought had run away in the chaos. In fact she was hiding in the back of a closet, terrified but fine. "Ummm, Sylvain...?" I hesitate to ask. But his hospitality is unshakeable. He loves cats, he says.

Meanwhile we are working virtually around the clock for days on end. The story burns through several news cycles without dying down. Everywhere we turn there are powerful stories begging to be told. The 87-year-old actress rescued after 32 hours under the rubble, who called the applause that welcomed her back to the surface "the most beautiful of my career"; the volunteer rescuers taking vacation time and risking their lives to tunnel through the rubble in search of survivors; the teams of volunteer psychologists counseling both them and the victims.

There are darker stories, too. The parents of the twins in my daughter's class lived in that building on Amsterdam Avenue, I later learn. They weren't home at the time, but they lost everything -- absolutely everything -- in the quake. And they were the fortunate ones. The death toll keeps rising in the days after the quake. Eventually it settles at 369 people, mostly in the capital.

(AFP / Yuri Cortez)

(AFP / Yuri Cortez)Back on the home front, the authorities have meanwhile found structural damage to our 1965 apartment building and declared it "high-risk." We decide we'd rather be homeless than go back. After more than a week with Sylvain -- whose hospitality is all the more amazing given that he is also working around the clock in extremely stressful conditions -- we move into an Airbnb and start looking for a new home. Somewhere seismically stable -- or more stable than Condesa, anyway. Unfortunately everyone else in Condesa seems to have the same idea. Houses and apartments in the surrounding neighborhoods suddenly vanish. Realtors start talking about crashes and bubbles.

One month on, we're still looking for a new home. But we consider ourselves lucky. The quake left far more tragic stories in its wake.