Waiting for justice: Rwanda’s ‘genocidaires'

AFP Johannesburg photographer Marco Longari visited Rwanda prisons in 2001, where he photographed some of the nation’s suspected “genocidaires”, accused of taking part in the 1994 massacres. It is only now that he is able to publish his images.

JOHANNESBURG, July 21, 2014 - I took these pictures of genocide suspects inside prisons in Rwanda in 2001 but it’s only now, 13 years later, that I’m able to publish them.

I spent a few years living in Rwanda, where I worked as a stringer for AFP. It wasn’t long after getting there that I knew I wanted to shoot inside the prisons. Everywhere you went, you could see prisoners dressed in pink uniforms being transported around the country, doing community work or attending trials: we called them the pink flamingos.

Unfortunately, the prisons were strictly off-limits. The government had built facilities for hundreds of people but many thousands were crammed inside and the conditions were deplorable.

Pink flamingos: A guard stands in front of some of more than 2,000 prisoners suspected of taking part in the 1994 Rwandan genocide. They were gathered in Butare's stadium, and were made to face victims of the massacre. September 29, 2002. (AFP Photo / Marco Longari)

Pink flamingos: A guard stands in front of some of more than 2,000 prisoners suspected of taking part in the 1994 Rwandan genocide. They were gathered in Butare's stadium, and were made to face victims of the massacre. September 29, 2002. (AFP Photo / Marco Longari)'It’s taken this long to make sense of the images'

Through a series of connections I was eventually able to gain access to a couple of prisons, including one in Kibuye on the shores of Lake Kivu.

Thirteen years have passed but the vivid images of those few hours spent tiptoeing in that parallel universe are still haunting me: I’ve been a privileged witness, but meeting those men was not an easy task. It’s taken me this long to make sense of the images I’d captured, and for other complicated reasons, I have had to wait until now before I could publish the pictures.

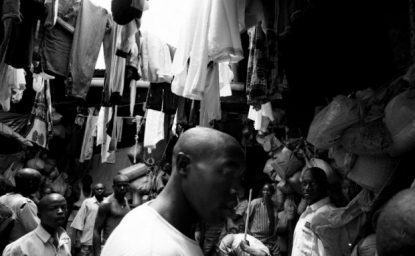

This file photo taken November 21, 2001, in Kibuye shows Rwandan inmates crowding the main yard at the local prison. (AFP Photo / Marco Longari)

This file photo taken November 21, 2001, in Kibuye shows Rwandan inmates crowding the main yard at the local prison. (AFP Photo / Marco Longari)Shuttling from hilltop to hilltop I’ve spent time collecting memories from the survivors, and I’ve been confronted with the terrible destiny of those who are left to live instead of others. Entire families in mourning, filling their day-by-day chores with the memories of those who are now gone.

Here I was: confronting those responsible for these losses. Would I be able to turn my camera on them? And if yes, to tell what: the stories of a bunch of killers or the madness of their condition, now, in a limbo resembling Dante’s inferno? Did they deserve any sympathy?

Inmates in a crowded cell in the Kibuye prison. (AFP Photo / Marco Longari)

Inmates in a crowded cell in the Kibuye prison. (AFP Photo / Marco Longari)I still remember the visit clearly. The stench was absolutely unbearable. Thousands upon thousands of prisoners were crammed into the prison, awaiting trial on genocide charges. They were accused of participating in the horrors of 1994, when close to one million people (mostly from the Tutsi minority) were slaughtered by their fellow countrymen in a period of just 100 days. In April this year, Rwanda commemorated 20 years since the start of the slaughter.

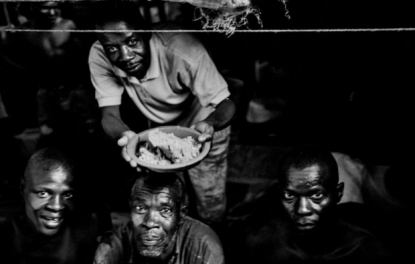

A group of men were cooking a meal of crushed cassava: one of them grabbed my arm inviting me for to sit down to share their food. I stopped and sat down on the filthy floor where water from the showers was streaming. I gulped, and politely refused the food.

Inmates prepare food. (AFP Photo / Marco Longari)

Inmates prepare food. (AFP Photo / Marco Longari)The main yard was packed with all sort of activities, and men in pink were getting a haircut, while others were praying.

Muslims, performing the midday prayer. No: I look closer, they were removing fleas from the woolen blankets used in their cells.

(AFP Photo / Marco Longari)

(AFP Photo / Marco Longari)Again a man pulls me into his cell. “Take my picture” he says, gazing in the darkness of his cell. “Take my picture”, he insists. Shooting films in those days, I brought with me only a handful of rolls counting the frames one by one choosing well what to shoot. It was pitch dark inside, not enough light: he was waiting. He sat in front of his sack looking sideway, I moved from the door frame to allow a bit of light to stream in. Click, one frame. “Go away, now” he told me allowing no reply.

Every room had these rickety wooden structures going up to the ceiling, row upon row of prisoners stacked on top of each other in tiny cells. It was incredible. I remember them telling me that when they slept at night, people were so squashed together that they all needed to turn over at the same time. From the ceiling in the middle of the rooms, you could see sacks tied up with long ropes. In these were the prisoners’ few possessions.

An inmate next to his possessions in Gisovu. October 31, 2001. (AFP Photo / Marco Longari)" title="An inmate next to his possessions in Gisovu. October 31, 2001. (AFP Photo / Marco Longari)

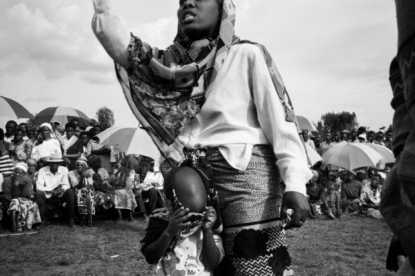

An inmate next to his possessions in Gisovu. October 31, 2001. (AFP Photo / Marco Longari)" title="An inmate next to his possessions in Gisovu. October 31, 2001. (AFP Photo / Marco Longari) This photo, taken October 16, 2001, in Runda shows residents gathering on a hillside for a gacaca session, where detainees accused of crimes committed during the genocide are confronted by members of the local community. (AFP Photo / Marco Longari)

This photo, taken October 16, 2001, in Runda shows residents gathering on a hillside for a gacaca session, where detainees accused of crimes committed during the genocide are confronted by members of the local community. (AFP Photo / Marco Longari)Gacaca community trials

Most of the prisoners were awaiting trial, though a few had already been sentenced and were appealing convictions. Sometimes, prisoners had the choice between appearing before a regular tribunal or a Gacaca, a traditional tribunal where an accused person is tried by members of a community he is said to have wronged.

The system of local justice is based on community participation and the judges are lay people. There are no lawyers. Some two million people were tried before the Gacaca in trials that ran from 2001 to 2012.

Sometimes during a Gacaca meeting, a member of the audience would shout out that the accused is responsible of acts of genocide; sometimes someone else would say he may has stolen a cow but certainly didn’t kill anyone. Old scores were sometimes settled. Everything was taken down by judges and sentences pronounced. Often the guy would walk back into the community as a free man.

(AFP Photo / Marco Longari)

(AFP Photo / Marco Longari)I never personally saw any violence in the prisons, or felt threatened. But complaints of abuses were rife. This woman, who was accused of genocide, said she had been raped in prison. Her son shelters from the camera behind his mother’s dress. “Jesus loves me,” his T-shirt affirms.

Rwanda is still coming to terms with what happened and not everyone involved in the genocide has yet been brought to justice. Many “genocidaires” have fled the country and changed their identities.

These images are not a tale of survival. Here I chose to confront the evil, and not to tell the stories of those who perished: every hill in Rwanda commemorates them.

Here are the stories of those whose lives have become a cage: they were pacing their narrow confines, measuring both their crime and punishment.

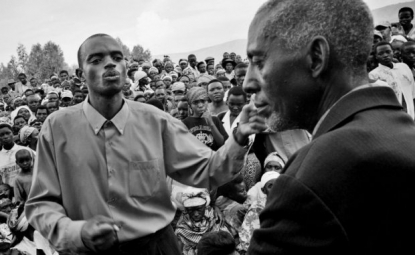

A gacaca tribunal. (AFP Photo / Marco Longari)

A gacaca tribunal. (AFP Photo / Marco Longari) A Rwandan civilian publicly confronts an inmate during a gacaca session, October 16, 2001. (AFP Photo / Marco Longari)

A Rwandan civilian publicly confronts an inmate during a gacaca session, October 16, 2001. (AFP Photo / Marco Longari)Marco Longari is a Johannesburg-based photographer for AFP.