The truths, the half truths and the lies

PARIS, November 19, 2015 -- The November 13 attacks in Paris unleashed an unprecedented storm of rumour and speculation on social media, surpassing the tidal wave that accompanied the Charlie Hebdo assaults in and around the French capital in January. This time around, the late hour of the strikes and the fact that they occurred almost simultaneously in several locations helped feed the rumor mill. But at the same time, there was less irresponsible content and less conspiracy theories than ten months earlier. It was as if lessons had been learned.

On Friday night I was at my house when the first tweets of the attacks began trickling in on my timeline. Soon it was a flood. My colleague Amandine Ambregni, who was on duty, had already forwarded what she considered the most important tweets to AFP editors. Some of the early information -- like that there had been a shooting at the Bataclan -- would end up being true. Other tweets much less so. People were tweeting that there had been shootings and explosions in the Halles neighbourhood -- these never happened. But in those early hours it was impossible to separate the truths, the half truths and the lies.

Rescuers evacuate people following the attacks. (AFP / Kenzo Tribouillard)

Rescuers evacuate people following the attacks. (AFP / Kenzo Tribouillard)When I left my house and headed to the office, I was taken aback by how many people were on the street, glued to their cell phones. Everyone I passed seemed to be on social media, trying to figure out what was going on. In such a situation, the slightest rumour can take on a life of its own.

Don’t get me wrong -- when major news like this breaks, social media is a formidable tool to find information, witness accounts, contacts and images. Social media today plays an indispensable role in the work of journalists, especially at AFP. Working on the ground and searching for sources remains indispensable and fundamental in our work. But it’s also necessary to be aware of the difficulty in finding the truth in the gigantic amount of information that is spewed onto social networks in a major story like this.

The prefect of the Ile-de-France region, Jean-Francois Carenco (r) shows his cell phone to an aide at a service to the victims of the attacks. (AFP / POOL / Lionel Bonaventure)

The prefect of the Ile-de-France region, Jean-Francois Carenco (r) shows his cell phone to an aide at a service to the victims of the attacks. (AFP / POOL / Lionel Bonaventure)During a story like this, it is essential for AFP’s social media team to keep a cool head in trying to get a handle on the situation. Part of our job is to signal to editors and reporters what appears to be credible information on Twitter, Instagram or other platforms, so they can check it out further. But at the same time, we can’t inundate journalists who are already drowning in leads and rumors. It’s not easy to find such a balance in a situation that’s unfolding with lightning speed, when official sources aren’t always available and when everyone is on edge.

To separate the serious from the absurd, one of the main criteria that we use is the source -- the person who is tweeting. For example, something that’s tweeted by a journalist -- a person who is theoretically trained to verify facts before publishing them -- has more chances of being true.

But in this day and age, noone has a monopoly on information. As far as I know, the first person to tweet the shootings at the Bataclan was Benoit Tabaka, a lawyer specializing in digital affairs whom I follow. He is not a journalist, but I know from experience that he’s someone trustworthy, who wouldn’t tweet just anything. If he’s talking about shots at the Bataclan, there is a strong probability that this is true. As it turned out to be. Contrary to the supposed shootings at the Halles, which were tweeted by a huge number of people who got carried away and just tweeted and retweeted mechanically, without stopping for a second to think and ask some questions.

Très nombreux coups de feu au Bataclan. Et ça continue à tirer.

— Benoit Tabaka (@btabaka) November 13, 2015A tweet from Benoit Tabaka on the night of the attacks reads "Lots of shots at the Bataclan. And the fire continues."

The supposed attacks on the Halles became the most viral untruth of the night. The following day, there were also the false ‘shooting’ at the town of Bagnolet, east of Paris, which ended up being firecrackers. There was also a major deployment of heavily armed police to the Pullman Hotel near the Eiffel Tower, which on Twitter transformed into an exchange of fire.

Most of these rumors aren’t launched maliciously. But it takes very little for the snowball effect to start. A simple police deployment, or a firecracker, or a backfiring exhaust pipe can quickly be transformed into rumors tweeted and retweeted thousands of times, feeding hysteria. It’s easy to get caught up -- since there had been numerous deadly attacks in the capital, the possibility of another one is entirely plausible.

Then there are rumors that turn out to be half truths. For example, a tweet of a photo claiming a bonfire set off by migrants in the northern town of Calais to ‘celebrate’ the Paris attacks. Other tweets talk about punitive anti-immigrant ‘expeditions.’ To be on the safe side, I alert our reporters to these, underlining that the information can turn out to be less than credible, as it’s always the same photo appearing in the tweets (we discover later that it was taken several weeks before). Once we check into it, it turns out that there was a fire in the vicinity that night -- not a joyful bonfire, but a blaze caused by an electrical malfunction that grew because of strong winds.

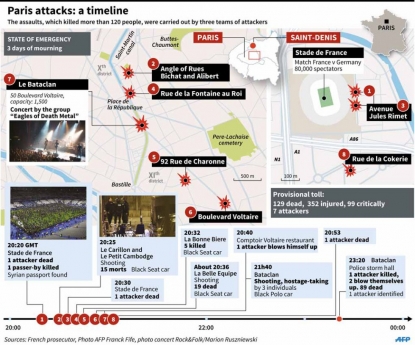

(AFP Graphics)

(AFP Graphics)The most frustrating thing for me in these situations is when non-verified information is tweeted right and left by users presenting themselves as ‘media outlets’ and taken as such by many users who believe whatever they say. A tweet talking of ‘confirmed attacks’ at the place de la Republique, at the Halles and at Trocadero -- where there turned out to be no such strikes -- was retweeted more than 7,000 times. Practically an identical tweet published by a complete unknown was retweeted more than 10,000 times. These chain reactions only help feed the general panic reigning that night.

How can these so-called information sites, run by volunteers without boots on the ground be believed in such dramatic and tense situations, when the media -- who have teams of 30 to 40 journalists on the ground -- are having trouble separating truth from fiction?

Some of these accounts -- followed by tens of thousands of people -- don’t even assume responsibility for their mistakes, simply erasing the false tweets without excuse or explanation. When AFP makes a mistake, we publish a correction.

Among the hoaxes of the night, there were the photos claiming to be of the Bataclan during the concert, which were actually photos of a concert in Ireland; images that supposedly showed the streets of Paris deserted on the day after the attack, which were actually taken in August; and the Empire State Building in New York lit up in the French tricolor.

Our colleagues, including Les Observateurs of France 24 television; Les Decodeurs of Le Monde, Liberations and Le Figaro newspapers did a remarkable job finding the false information.

But in the end, such hoaxes were relatively few compared to all the conspiracy theories, malicious rumors and all the calls to violence that followed the attacks in January on Charlie Hebdo and the kosher supermarket.

If you're trying to follow the news in Paris, look for sources, like @AFP, that name their sources, rather than unconfirmed reports.

— L. Rhodes (@Upstreamism) November 14, 2015This time, social networks were used more to search for the missing than to incite hatred. The notices searching for missing loved ones were by far the most retweeted and sometimes accomplished their task. We also saw a lot of people pass on appeals from the authorities not to disseminate unfounded rumors, photos of the crime scenes or police movements. We also saw people call on authors of the most ‘fantasy’ tweets to rely on recognized media outlets that, even though they too make mistakes, for the most part publish the most viable information possible.

It was as if, in the space of some ten months, users of social media had become a bit more adult, more responsible. A sign of things to come? One can only hope.

Gregoire Lemarchand is the head of social media at AFP in Paris. Follow him on Twitter.

This blog was written with Roland de Courson (@rdecourson) and translated by Yana Dlugy (@yanadlugy).

(AFP / Eric Feferberg)

(AFP / Eric Feferberg)