A traveler comes home

SAINT-PABU, France, January 22, 2015 – Writing a profile of Jacques Lhuillery is like walking down a winding road, with many forks. Starting from the man I knew and discovering, with each new friend I speak to, with each hilarious or moving anecdote, a new Jacques, another faraway land, another of his lives of which I knew nothing.

The head of AFP’s Japan bureau, who died of cancer aged 61, learned to speak Dutch while living in Saudi Arabia. He was the star of the annual Mardi Gras carnival in a small town in the south Netherlands, and he played petanque with an African head of state over drinks of ‘pastis’.

Jacques was devastated by the murder in Ivory Coast of his friend and colleague Jean Helene, and was himself gravely injured in a fire at his home in Nigeria. But he never lost the rambunctious sense of humour, the actor’s talent and brazen nerve that seemed to open doors wherever he went.

“I was a keen actor in my youth,” he once told his deputy at AFP’s bureau in Abidjan, Laurent Banguet. “It helps me every day to play the part of bureau chief. Imagine, Laurent, that you’re on a stage – it’s no more complicated than that!”

Jacques Lhuillery in a Bete village in Ivory Coast in 2003 (AFP / Georges Gobet)

Jacques Lhuillery in a Bete village in Ivory Coast in 2003 (AFP / Georges Gobet)He could well have made a living on the stage – impersonating Chirac, or Coluche, or anyone for that matter. But Jacques Lhuillery chose far more dangerous arenas to build his career as a journalist: Iran during the 1979 revolution, violence-wracked Lebanon, Ivory Coast in crisis, tumultuous Nigeria, Tunisia during the Arab Spring – as well as quieter postings to Spain, the Netherlands and Japan, his last one.

An incredible talent for languages meant he soon found his feet wherever he landed. He was one of the rare AFP journalists to speak fluent Dutch, which he learned in a few months as a young man doing voluntary service in Saudi Arabia – where he was bored stiff.

Star of a Dutch carnival

“One of the only things to do out there were the film nights at the French embassy,” recalled his old friend Ruud Zwaans, a Dutch businessman posted to the austere Gulf kingdom around the same time. “That’s where we met. To pass the time, I used to teach Jacques Dutch - and he taught me French in return. He was a talented student.

“Much later, after he was named head of the AFP bureau in The Hague, he would come each year for the carnival in Littard, my hometown in Limburg province. He had learned the words to all the old songs in Dutch dialect, and ended up becoming something of a local star. They nicknamed him ‘the Frenchman’.

“He had this incredible ability to plunge himself into other people’s worlds, to truly appreciate them, and make them love him in return.”

Jacques Lhuillery interviewing Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in 2013 (AFP Photo / Toshifumi Kitamura)

Jacques Lhuillery interviewing Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in 2013 (AFP Photo / Toshifumi Kitamura)“He knew how to speak to a cocoa farmer, and how to interview a head of state in a country at war,” said the photographer Georges Gobet, who worked with him in Abidjan. “He was at ease in all walks of life, and you could rely on him to get hold of information where others failed.”

Each time he arrived in a new country, Jacques made it his challenge to get an exclusive interview with the head of state or government. He never gave up, and usually pulled it off in the end. Even in Japan, where the mission is all but impossible for a foreign journalist.

'Have Jacques call me at 8:12 sharp,' says president

“He was charming, he was persuasive – and he could put on a hell of a performance if need be. Jacques knew how to adapt to his audience, whether he was speaking to a car park attendant, a suited diplomat or a president-general with a clinking chestful of medals,” said Laurent Banguet.

“He had the Togolese president Gnassingbe Eyadema clapping with both hands and asking for more. Like once with a memorable game of petanque, in the president’s stronghold in north Togo, over obligatory drinks of pastis. Or in the regular phone chats in which the president shared with him his take on the crisis in Ivory Coast. Eyadema wouldn’t speak to me, his deputy.

“‘Have Jacques call me tomorrow at 8:12 am sharp!’ he would say. Why 8:12? Jacques later explained that Eyadema was an avid listener to Radio France Internationale, and that the time marked one of his less-favoured programming slots.”

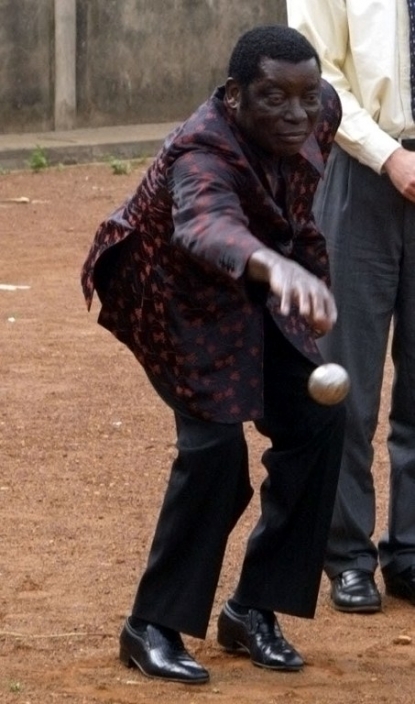

Gnassingbe Eyadema, Jacques Lhuillery's friend and then president of Togo,

playing petanque in 2003 (AFP / Georges Gobet)

Jacques’ career was anything but an easy ride. In April 1996, when he was Beirut bureau chief, the Israeli army launched its “Operation Grapes of Wrath” against Hezbollah positions in south Lebanon. Shells rained down on a UN peacekeepers’ camp near the village of Qana, killing more than 100 civilians. Sent to the scene, Jacques headed to the local hospitals and – to provide the agency with a death toll – set about counting the bodies.

An experience that would mark him for life, as was clear from the message he sent 17 years later to Agnes Bun, an AFP video reporter who had just returned from covering a devastating typhoon in the Philippines. The two journalists had never met. But Jacques was moved to tears by the blog the young woman, 35 years his junior, wrote about her experience.

'It will not harden you'

“I want to tell you how much I was touched, shaken even, by your story, how it addresses the unspeakable with such dignity. I must say it brought back memories and emotions of my own,” he wrote, before telling her of his own macabre experience in Lebanon.

“I had never wept so much in my career. When I got home to Beirut, I gathered my four children in my arms and I held them close, tight against me, and covered them with kisses. I was not cut out for this kind of thing, but I found myself in the Iranian civil war, in the war with Iraq, covering African coups (not a pretty sight), etc. You get over it, with some wounds to the heart, and scars etched on your memory, but you do get over it. Rest assured, it will not harden you. It will make you appreciate your happiness all the more, though it will also teach you how fragile it can be.”

UN soldiers and civilians evacuate the bodies of victims of the shelling of Qana, on 18 April 1996 (AFP Photo / Joseph Barrak)

UN soldiers and civilians evacuate the bodies of victims of the shelling of Qana, on 18 April 1996 (AFP Photo / Joseph Barrak)A happiness Jacques found until the end of his life with his wife Denise, his “sweetheart” who was at his side on every posting including the most dangerous, and the four children he talked about constantly.

Jean Helene's death

Tragedy hit closer to home in 2003 when his friend Jean Helene, RFI’s correspondent in Abidjan, was assassinated by a policeman, in a climate of anti-French hysteria whipped up by pro-government Ivorian media.

“Overcome with grief and anger, Jacques was still the first to head to the crime scene, with the French ambassador,” recalled Michele Leridon, at the time AFP’s chief editor for Africa. “It left a deep wound.” In an interview with the BBC the following year, as the murderer stood trial, Jacques gave this acid assessment: ‘When you don't have a high IQ and you read every day that the French are the enemy, it can be dangerous.’

“Years later, as Jean Helene’s Italian partner still struggled to come to terms with the tragedy, Jacques wrote a long piece, his emotion still fully intact, just to help her,” said Michele Leridon.

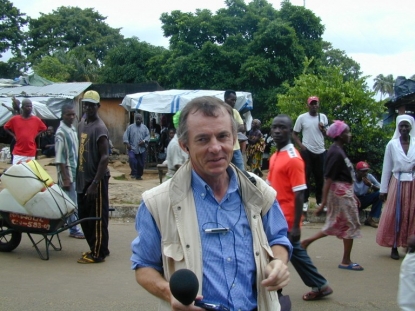

RFI reporter Jean Helene, Jacques Lhuillery's friend murdered in Ivory Coast in 2003, seen on assignment in Liberia

(AFP Photo / Massimo Alberizzi)

A Chinese language graduate, Jacques never managed to put that skill into practice at AFP - despite many attempts. “I joined AFP to travel to Asia, it’s my passion in life. As a result I have found myself in The Hague, Madrid, Beirut, Abidjan,” he would complain jokingly to Michele Leridon after being turned down for Hanoi - throwing in impersonations of the numerous bosses who kept sending him places he had no desire to go…

“But I don’t regret any of it,” he went on. “That’s also what AFP’s about, seizing opportunities as they arise, discovering horizons you would never have considered.”

Respect for African people

Whatever new horizon he was bound for, Jacques spared no effort in getting to grips with his host country. The hundreds of yellowing files still stacked in his old Lagos office are a testament to his determination to immerse himself in that fascinating, complex place. He also had a gift for winning the affection of those around him – whether his sources or his subordinates.

Jacques Lhuillery in a Bete village in Ivory Coast in 2003 (AFP / Georges Gobet)

Jacques Lhuillery in a Bete village in Ivory Coast in 2003 (AFP / Georges Gobet)“He is someone who would teach you everything, provided you were willing to learn,” recalled Fiacre Vidjingninou, who Jacques hired as an AFP correspondent in Benin. “He wasn’t one of those white guys who turn up clinging to their bookish knowledge. He knew how to forge an opinion based on his own experiences. And he had respect for African people.”

In 2010, when Jacques was seriously injured in an accidental fire in his Lagos apartment block, the Togolese president immediately sent a minister to his bedside.

Cartoon-like explosions of anger

Cheek and charm aside, Jacques could also raise a storm when needed.

“Blistering barnacles! Cartoon-like explosions of anger that leave you with your hair plastered back, your ears ringing and bright colours blinking in your brain,” recalled Laurent Banguet. “A wave of decibels in a raucous, booming voice that left no one unscathed. The auditory equivalent of a pair of slaps, Lino Ventura-style. Summary, but effective.”

But laughter was the ultimate weapon of the six-foot colossus that was Jacques.

“Jacques was an exuberant and very, very funny person, with a wonderful sense of humour – rather in the style of Charlie Hebdo in fact. The real life and soul, a born entertainer,” confirmed his friend the AFP journalist Christian Chaise. “He had a knack for seeing the funny side in every situation.”

Much as he himself was generous and straight-down-the line, Jacques was pitiless towards people he saw as phoney or dishonest – tarring them with all manner of corrosive nicknames before bursting with laughter.

Jacques Lhuillery reporting from the Yasukuni shrine in Tokyo, where war criminals are venerated,

on August 15, 2012, the anniversary of Japan's 1945 defeat (AFP / Roland de Courson)

“But the laugh I preferred in him was the one that came without warning, without reason. Just because he found life amusing, because he felt good, with his family, his friends,” said Laurent Banguet. “It would start with a rumble, deep down in his belly. From there it bubbled up to his nose, spun round 180-degrees into his throat and burst out like a bright clarion call, declaring its owner’s joy for kilometres all around. That laugh was a challenge to the skies above and the earth beneath his feet. It thumbed its nose at the gods, stopped fools in their tracks, and declared its love to the whole wide world.”

Sumo and corrida

Jacques’ other secret weapon was his pen. Trained at France’s Lille journalism school, he was a brilliant and often hilarious writer, who delighted the readers of AFP’s blogs with his meticulously-observed posts about Japan.

A journalist of the old school, he understood right away the power of online media and in the last few years of his career wrote extensively for the blogs, marveling about every aspect of his latest host country, so different from the tough terrain he traveled for much of his life, and drawing extraordinary parallels between Sumo and corrida, or Lagos and Tokyo.

Jacques Lhuillery in Tokyo in August 2012 (AFP / Roland de Courson)

Jacques Lhuillery in Tokyo in August 2012 (AFP / Roland de Courson)“He was bright, he was smart, he was a natural-born writer… and he knew it!” said Pierre Ausseill, another of his longtime friends. “But the best thing about him was that he never let himself be blinded by his talent. In 2011, at the height of the Tunisian revolution, when he took over from me on the story, I was surprised at how nervous he seemed. He was afraid he would not be up to the task. I had to reassure him, even though he’s got ten times my experience. Jacques had that permanent feeling of insecurity that makes truly excellent journalists. He was the real thing.”

Real as his big, strong voice. Real as his bear-like figure and impish grin. Real as the rocky coastline of his native Brittany where, tonight, he has come to rest.

(The author would like to thank Pierre Lhuillery, Georges Gobet, Pierre Ausseill, Laurent Banguet, Pierre Feuilly, Phil Hazlewood, Christian Chaise, Michele Leridon, Gerard Vandenberghe, Miguel Enesco, Fiacre Vidjingninou and Ruud Zwaans for their contributions to this article)