Reporting under lese majeste

Bangkok -- As Thailand readied to hold its first coronation in 70 years, rich in pageantry and rituals, I faced a tricky situation. As a journalist, my job was to write as much as possible about the new sovereign and his reign. But in Thailand, writing the wrong thing about the king can cost you your freedom.

The country has some of the strictest lese majeste laws in the world. Forget writing something critical -- that’s completely out of the question. Often reporters find themselves censured for writing something the royal family dislikes. Once, a person was jailed because he posted comments on Facebook that were deemed insulting to the late king’s dog.

Thailand's King Maha Vajiralongkorn is carried in a golden palanquin during the coronation procession in Bangkok on May 5, 2019. (AFP / Manan Vatsyayana)

Thailand's King Maha Vajiralongkorn is carried in a golden palanquin during the coronation procession in Bangkok on May 5, 2019. (AFP / Manan Vatsyayana)I was warned of this before I ever set foot in the country. “There are things that you should never discuss,” a helpful Thai diplomat in Paris told me after I applied for my visa. “The royal family is sacred. You’ll have to censor yourself.”

A year later, I had to cover the coronation of the new king, Maha Vajiralongkorn. Although he technically ascended to the throne in 2016 when his father died, he waited until 2019 to be officially coronated, as the country mourned his long-reigning and much-beloved father.

Royal Thai police stand guard near the Grand Palace in Bangkok on May 3, 2019, ahead of Thailand's King Maha Vajiralongkorn's coronation which will take place from May 4 to 6. (AFP / Manan Vatsyayana)

Royal Thai police stand guard near the Grand Palace in Bangkok on May 3, 2019, ahead of Thailand's King Maha Vajiralongkorn's coronation which will take place from May 4 to 6. (AFP / Manan Vatsyayana)The festivities took place over three days, televised live by all the country’s channels. I dutifully wrote how the ceremony started at 10:09, the hour chosen by royal astrologers, how the new king, dressed in a white robe, received holy water, how his crown of gold and diamonds was placed on his head.

This screengrab from Thai TV Pool video taken on May 4, 2019 shows Thailand's King Maha Vajiralongkorn facing the audience wearing the gold crown while sitting on the throne during his coronation at the Grand Palace in Bangkok. (AFP / Thai Tv Pool)

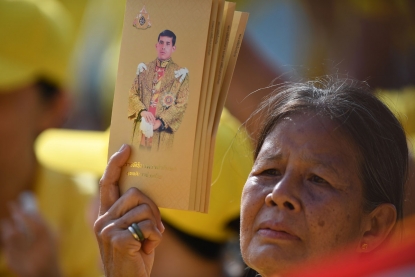

This screengrab from Thai TV Pool video taken on May 4, 2019 shows Thailand's King Maha Vajiralongkorn facing the audience wearing the gold crown while sitting on the throne during his coronation at the Grand Palace in Bangkok. (AFP / Thai Tv Pool) A woman holds a brochure with a portrait of Thailand's King Maha Vajiralongkorn as people wait for him and Queen Suthida to appear on the balcony of Suddhaisavarya Prasad Hall of the Grand Palace to grant a public audience on the final day of his royal coronation, May 6, 2019. (AFP / Lillian Suwanrumpha)

A woman holds a brochure with a portrait of Thailand's King Maha Vajiralongkorn as people wait for him and Queen Suthida to appear on the balcony of Suddhaisavarya Prasad Hall of the Grand Palace to grant a public audience on the final day of his royal coronation, May 6, 2019. (AFP / Lillian Suwanrumpha)

The next day I wrote about the huge royal procession during which the king was transported through the streets of Bangkok in a golden palanquin and carried by 16 soldiers who walked 75 steps per minute. I described the thousands of Thais who prostrated themselves before the king -- prostration before the king and his image is common in Thailand and was perhaps one of the things that shocked me most when I arrived -- lying on the hot asphalt. Dozens of them ended up fainting.

This handout from the Thai Royal Household Bureau taken and released on May 5, 2019 shows Thailand's Queen Suthida (front R) marching beside the golden palanquin of King Maha Vajiralongkorn as it is carried out of the Grand Palace for his coronation procession, May 5, 2019. (AFP / Handout)

This handout from the Thai Royal Household Bureau taken and released on May 5, 2019 shows Thailand's Queen Suthida (front R) marching beside the golden palanquin of King Maha Vajiralongkorn as it is carried out of the Grand Palace for his coronation procession, May 5, 2019. (AFP / Handout)AFP had a team of four photographers and reporters following the procession. We were given strict rules to obey -- we had to dress in dark blue clothes, with a yellow tie, the color of the monarchy and black, polished shoes. We had to stay at least five meters from the monarch. We couldn’t film his back. We couldn’t use ladders, as it is forbidden to be higher than the king. We had to bow deeply when he passed.

Thailand's King Maha Vajiralongkorn makes a speech beside Queen Suthida on the balcony of Suddhaisavarya Prasad Hall of the Grand Palace as they grant a public audience on the final day of his royal coronation in Bangkok on May 6, 2019. (AFP / Jewel Samad)

Thailand's King Maha Vajiralongkorn makes a speech beside Queen Suthida on the balcony of Suddhaisavarya Prasad Hall of the Grand Palace as they grant a public audience on the final day of his royal coronation in Bangkok on May 6, 2019. (AFP / Jewel Samad) Thailand's Princess Sirivannavari Nariratana (L) takes a photo of her siblings Prince Dipangkorn Rasmijoti (C) and Princess Bajrakitiyabha Mahidol as they wave from the balcony of Suddhaisavarya Prasad Hall of the Grand Palace during a public audience, May 6, 2019. (AFP / Jewel Samad)

Thailand's Princess Sirivannavari Nariratana (L) takes a photo of her siblings Prince Dipangkorn Rasmijoti (C) and Princess Bajrakitiyabha Mahidol as they wave from the balcony of Suddhaisavarya Prasad Hall of the Grand Palace during a public audience, May 6, 2019. (AFP / Jewel Samad)

The images of the new king were magnificent -- dressed in golden clothes, he was surrounded by a thousand soldiers. The Thais will probably never have an opportunity to see their king this close again. Up till now he had rarely appeared in public, contrary to his father who used to travel throughout the country.

I wrote all these things, but when I left the bureau at midnight, I couldn’t help but feel frustrated.

A woman bows to pay her respects as Thailand's King Maha Vajiralongkorn arrives at the Grand Palace for his coronation in Bangkok on May 4, 2019. (AFP / Manan Vatsyayana)

A woman bows to pay her respects as Thailand's King Maha Vajiralongkorn arrives at the Grand Palace for his coronation in Bangkok on May 4, 2019. (AFP / Manan Vatsyayana)What did the Thais think of their new king? How did he intend to rule? The Thai royal family is among the richest royals in the world, but what exactly do they possess? Where will the new sovereign spend his time? (for years, he has spent most of it at the luxury residences he owns in Germany’s Bavaria region). So many questions remained unanswered.

Lese majeste laws are no joke in Thailand. Offenders can receive from three to fifteen years in prison.

Since the 2014 coup that brought the military to power here, some 100 people have been prosecuted under these laws. Although no new cases have been brought up over the past year, a dozen people remain behind bars for the offense.

This handout from the Thai Royal Household Bureau taken on May 4, 2019 and released on May 5, 2019 shows officials placing a white rooster and Siamese cat on a pillow as part of a housewarming ritual intended to bring good tidings, as part of the coronation ceremonies. (AFP / Handout)

This handout from the Thai Royal Household Bureau taken on May 4, 2019 and released on May 5, 2019 shows officials placing a white rooster and Siamese cat on a pillow as part of a housewarming ritual intended to bring good tidings, as part of the coronation ceremonies. (AFP / Handout) This framegrab from Thai TV Pool video taken on May 5, 2019 shows Thailand's King Maha Vajiralongkorn lighting a candle in a ceremony in Wat Pho or the Temple of the Reclining Buddha during his coronation procession in Bangkok. (AFP / Thai Tv Pool)

This framegrab from Thai TV Pool video taken on May 5, 2019 shows Thailand's King Maha Vajiralongkorn lighting a candle in a ceremony in Wat Pho or the Temple of the Reclining Buddha during his coronation procession in Bangkok. (AFP / Thai Tv Pool)

A “cyberpatrol” of bureaucrats, as well as volunteers from royalist groups (the most notorious of them is called “The Garbage Collection Organization”), scour the internet for possible offenders.

In December 2018, two Thai dissidents who broadcast anti-royal programs from neighboring Laos to where they had fled, were found dead.

A florist works as a portrait of Thailand's Kimg Maha Vajiralongkorn and his father the late king Bhumibol Adulyadej (C) is displayed in a shop in Bangkok on May 2, 2019. (AFP / Manan Vatsyayana)

A florist works as a portrait of Thailand's Kimg Maha Vajiralongkorn and his father the late king Bhumibol Adulyadej (C) is displayed in a shop in Bangkok on May 2, 2019. (AFP / Manan Vatsyayana)During the rare occasions that I dared pose questions about the royal family to people I interviewed, my queries were met with a polite smile that Thais use to get out from a delicate situation and hide their embarrassment.”

At times, the lese majeste laws meant that my work took a decidedly absurd turn.

This handout picture taken and released by Thai Royal Household Bureau on May 1, 2019 shows Thailand's King Maha Vajiralongkorn (R) and Queen Suthida during their wedding ceremony in Bangkok. (AFP / Handout)

This handout picture taken and released by Thai Royal Household Bureau on May 1, 2019 shows Thailand's King Maha Vajiralongkorn (R) and Queen Suthida during their wedding ceremony in Bangkok. (AFP / Handout)A few days before he was officially coronated, Maha Vajiralongkorn, who has been thrice divorced, wed his fourth wife, a woman who had been his companion for a long time, a former air stewardess who was at one point named as his bodyguard. Naturally, there was great interest in learning more about Queen Suthida. But because she was now protected by the lese majeste laws, I couldn’t learn anything about her background. I couldn’t even get a confirmation of her age.

The Thai royal family has always cultivated an air of mystery around itself, one of the reasons it has kept its hold on power.

This handout from the Thai Royal Household Bureau taken and released on May 5, 2019 shows Thailand's King Maha Vajiralongkorn (centre L) interacting with his sister Princess Sirindhorn (front 2nd R) and Queen Suthida (front bottom R), as his sister Princess Chulabhorn (2nd L) watches during the coronation ceremony.

(AFP / Handout)

This handout from the Thai Royal Household Bureau taken and released on May 5, 2019 shows Thailand's King Maha Vajiralongkorn (centre L) interacting with his sister Princess Sirindhorn (front 2nd R) and Queen Suthida (front bottom R), as his sister Princess Chulabhorn (2nd L) watches during the coronation ceremony.

(AFP / Handout)“Since I was a child, I have been conditioned not to doubt and to consider the monarchy as infallible,” a Thai journalist told me. “I have never spoken about it at the office. I have never even discussed it with my parents or my husband.”

Another colleague went a bit further. “There is no specific definition of this crime, which leaves the authorities wide latitude to interpret it as they see fit, and often to the detriment of their political foes,” she told me. “If we can’t talk about our history, the future of our society is threatened.”

Thailand's King Maha Vajiralongkorn arrives at the Grand Palace for his coronation in Bangkok on May 4, 2019. (AFP / Jewel Samad)

Thailand's King Maha Vajiralongkorn arrives at the Grand Palace for his coronation in Bangkok on May 4, 2019. (AFP / Jewel Samad)But when I tried to bring up the new king’s personality and his escapades, which have been reported by foreign media, she shut down. “This is of no importance,” she told me. “This image is disappearing, in favor of an image of a sacred and powerful king.”

“And you? What purpose does it serve for you to constantly criticize your leaders?” she asked me. I had little choice but to answer with the same smile that the Thais use to get out of a delicate or embarrassing situation.

Well-wishers march with pictures of Thailand's King Maha Vajiralongkorn during a procession near the Grand Palace to pay their respects to the King in Bangkok on May 7, 2019. (AFP / Jewel Samad)

Well-wishers march with pictures of Thailand's King Maha Vajiralongkorn during a procession near the Grand Palace to pay their respects to the King in Bangkok on May 7, 2019. (AFP / Jewel Samad)