Involuntary reporters

Paris, March 25, 2016 -- There was a time when witnesses to attacks only thought to flee. Today, some also take out their smartphones to record what’s happening. For journalists, this has meant a world of difference.

A few minutes after explosions rip through Brussels’ airport on March 22, pictures of the attacks start to circulate on social media networks. This makes sense -- the killings occurred in a place where there were thousands of people gathered from various countries, in a city with a well-functioning communications network.

One of the first videos is of people fleeing the smoke-filled airport. When you see it, you instantly understand that something very serious has happened. A little while later, there come images of blood-stained victims in clouds of dust. When the second strike hits the Maelbeek metro an hour later, photos and videos of that attack also begin to circulate nearly instantly.

Journalists can’t be everywhere at once. Sometimes they are ‘lucky’ and witness an event like this first-hand. But for several years now, what’s known as UGC (user-generated content) -- the photos and videos that eyewitnesses put on social media -- has been playing a key role in media reports, showing events as they unfold.

Two women wounded in the twin blasts at Brussels airport in Zaventem (AFP / Georgian Public Broadcaster / Ketevan Kardava)

Two women wounded in the twin blasts at Brussels airport in Zaventem (AFP / Georgian Public Broadcaster / Ketevan Kardava)For journalists, this has meant that there are now two places to cover -- the actual physical place of an event and the virtual world, where those caught up in an event put up their videos and photos, which we then have to chase up.

To some, this ‘chasing up’ can seem distasteful, just like when photographers on the scene take pictures of the victims. But for news-gathering purposes, it is essential and it has come to complement the work of professional photographers and camerapeople of a media organization like AFP.

Fooling the media

When the Brussels attacks struck, there were four of us in AFP’s social networks cell, which is part of the editor in chief’s office. In a city like Brussels, well covered by a 4G network, taking a 30-second video and uploading it onto a social media network doesn’t take very long. And as the attacks happened in rush hour, there were plenty of eyewitnesses.

Our first priority was to focus on those photos and videos that answer to AFP’s editorial standards, so we skip over those that are degrading to the victims or that are too bloody. We also have to be careful to avoid the usual traps -- images and videos of other events that some people post on social networks to fool the media. That morning, some fall into the trap and use images taken during an attack in Moscow in 2011 and presented like those from the Brussels’ strikes.

Rescue teams evacuate wounded people outside the Maalbeek metro station (AFP)

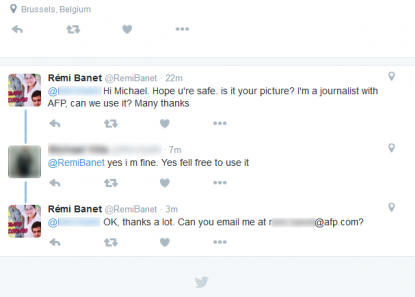

Rescue teams evacuate wounded people outside the Maalbeek metro station (AFP)Once we see an interesting image, we contact the person who published it. This can be delicate. A person who has just witnessed a deadly attack can be in a state of shock. On the one hand, you don’t want to hound that person. On the other, it’s legitimate to suppose that a person who has just posted an image on a social network like Twitter is conscious of what he or she is doing and wants that the images are seen by as many people as possible.

UGC spree

Most of the people we contact that day don’t mind if we use their images. Some people contact AFP directly, offering photos and videos.

In this situation, you have to act quickly, before other journalists from all over the world don’t contact the same person, often without any tact, so that the person no longer answers anyone. The first thing we do is to ask if the person is safe. Then we ask if he or she is the author of the image online (sometimes people publish images taken by others without saying so) and then we ask if we could use the image ourselves.

A grab from an amateur video shows commuters being evacuated from a train after the explosion at the Maalbeek station (AFP / EurActive / Evan Lamos)

A grab from an amateur video shows commuters being evacuated from a train after the explosion at the Maalbeek station (AFP / EurActive / Evan Lamos)Some media don’t go through this process and publish whatever they find online. But AFP is a global news agency and the images that we run can be published all over the world, which means that we have to scrupulously observe copyright principles and show a certain standard of behavior. Therefore we always ask for permission to use the image by email, or at least through Twitter. We also make sure that the image is authentic. The easiest way to do this is to use Google Reverse Image Search, to make sure that the image is not of an event that has already passed. If we have the slightest doubt about an image, we drop it.

Sometimes people refuse to let us use images that they posted on Twitter. In these cases, we don’t insist. Same thing for those who don’t reply to our inquiries -- it’s probably because hundreds of our colleagues are already saturating their inboxes with similar requests. We try and focus on a small number of interesting images.

To find a good UGC, an excellent knowledge of the social network world is essential. The photo at the top of this blog was picked up by the New York Times, The Economist and other publications the world over. It was taken by a passerby who posted it on Twitter at 11:05 am with the hashtag #Maelbeek. At 11:13, we ask him for permission to use it, which he gives us at 11:29 via Twitter, then by email at 12:20. This person has only about 50 followers on Twitter and so his incredibly strong photo was retweeted only twice. We found it thanks only to a careful monitoring of Twitter.

And the money in all this? Sometimes people ask us for compensation, but it’s rare. Not one did following the Brussels attack.

Remi Banet and Gregoire Lemarchand are journalists at AFP’s social networks cell in Paris. This blog was written with Roland de Courson and translated by Yana Dlugy in Paris.