As paradise melts and crumbles

Chamonix, France -- You never forget your first time. Mine began around 5 o’clock in the morning, as we left the hut. Not quite awake yet, we climb slowly up the glacier, headlamps lighting the way and hearts fluttering with anticipation of the unknown. Up above, at the pass marking the border between France and Switzerland, a glare of sorts. An immense glacial cirque, a wide bowl-shaped hollow covered in snow comes into view, lit up by the dawn.

A black mountain bird silently soars above us. It takes my breath away to witness such beauty, knowing that not a soul can see it from the valley below. To discover this universe of rock, snow and ice, you need to climb. Not many have done so, not many have seen.

A crow flies near the Aiguille des Leschaux and the Grandes Jorasses near the Couvercle Refuge (mountain hut) on June 18, 2019 in Chamonix. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)

A crow flies near the Aiguille des Leschaux and the Grandes Jorasses near the Couvercle Refuge (mountain hut) on June 18, 2019 in Chamonix. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)Some ten years earlier, I had made a vow. I was a teenager and came to see the Mer de Glace, France’s largest glacier that lies above the famed town of Chamonix, the birthplace of alpinism. As I stood at the Aiguille du Midi observatory at 3,800 meters with the other tourists, I saw a handful of handsome young climbers, ropes slung around their shoulders, putting on their crampons and taking off confidently on the glacier. I promised myself that one day I would go with them.

Aspiring mountain guide Yann Grava walks on the Mer de Glace glacier in Chamonix on June 17, 2019. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)

Aspiring mountain guide Yann Grava walks on the Mer de Glace glacier in Chamonix on June 17, 2019. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)And since that first time, I’ve done it nearly every summer. With every climb, my love for the mountains has only matured and grown stronger. The silence, the fragile beauty. The warmth of the mountain huts, with their moments of sublime exhaustion and plentitude. The inconveniences, like the absence of a shower, don’t matter. No cell signal and no wifi? No problem. During the day, the pleasure of physical exertion. And the joy, every time, of seeing what lies behind the mountain as you climb up to the pass. It’s always another mountain. And it is always glorious.

A man stands above the Mer de Glace glacier on June 19, 2019, in Chamonix. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)

A man stands above the Mer de Glace glacier on June 19, 2019, in Chamonix. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)This summer’s trip, however, was tinged with sorrow, for I went to tell the story of my love slowly dying. Together with AFP’s Italy-based photographer Marco Bertorello, we went to document how climate change is affecting the Mer de Glace, which is disappearing more and more every year.

A man walks near big sheets used to slow down the melting above the grotto carved inside the Mer de Glace glacier in Chamonix on June 17, 2019. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)

A man walks near big sheets used to slow down the melting above the grotto carved inside the Mer de Glace glacier in Chamonix on June 17, 2019. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)We spent four days up high, following Yann, a 33-year-old who will complete his high-altitude guide training next year. I had met him the previous year during an outing in the area. Like the old timer guides, he speaks little but misses even less. He looks over you, protects you from the hidden dangers, gives assurances, without being condescending.

Aspiring Mountain guide Yann Grava poses behind a window at the Couvercle Refuge (mountain hut) on June 18, 2019 in Chamonix. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)

Aspiring Mountain guide Yann Grava poses behind a window at the Couvercle Refuge (mountain hut) on June 18, 2019 in Chamonix. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)When he tells you to walk along a snow bridge above a crevasse yawning without end down below, you go. He wouldn’t tell me to go if I couldn’t do it. At least that’s what you tell yourself as you advance, step by step, on that snow bridge, hands in the air, nothing to grab onto, just a rope around your waist so that in case you fall, Yann can pull you out.

A woman walks near the Mer de Glace glacier on the path to the Refuge du Couvercle in Chamonix on June 18, 2019. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)

A woman walks near the Mer de Glace glacier on the path to the Refuge du Couvercle in Chamonix on June 18, 2019. (AFP / Marco Bertorello) Climbers walk around wide crevasses on the Mer de Glace glacier in Chamonix on June 18, 2019. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)

Climbers walk around wide crevasses on the Mer de Glace glacier in Chamonix on June 18, 2019. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)

After I cross, the bridge, not exactly sturdy to begin with, looks ever frailer. Not very reassuring for Marco. Don’t worry, you got it, you got it, Yann assures him. As usual, he turns out to be right.

Photos were the priority on this assignment, so Marco regularly asks to stop on the glacier. Sometimes Yann agrees -- “take your time,” -- sometimes he doesn’t -- “it’s too dangerous.”

Marco lives in the Piedmont (literally, “foot of the mountain” in Italian), so he is at home in this environment. But it’s his first time in this area. He has the advantage of discovering this place. I already know all its corners and stories. I want to speak to the climbers, so that they can tell me how precisely climate change has been affecting the area, to give their views on the subject. And to speak to climbers, you have to climb.

The Mer de Glace glacier is pictured in Chamonix on June 17, 2019. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)

The Mer de Glace glacier is pictured in Chamonix on June 17, 2019. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)In Chamonix, you usually see them early in the morning as they do a quick shopping run before taking off again into the wilderness. Often, they have just returned the night before, just enough time to take a shower and share a meal with buddies before leaving again. They are more than happy to leave the streets of the village to the tourists, the dreamers, the shoppers.

During our first day climbing, Marco is shocked to see that the Mer de Glace is gray, covered with rocks and with nary a patch of snow showing. As he would say later, it gave him the impression of a “dying beast.” To reach it, we had to climb down several hundred meters from the starting point at gare du Montenvers, a train stop above Chamonix, (the more the glacier melts, the further down you have to climb). He would call it later a “vertical cemetery.”

People walk on stairs built to reach the Mer de Glace glacier in Chamonix on June 17, 2019. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)

People walk on stairs built to reach the Mer de Glace glacier in Chamonix on June 17, 2019. (AFP / Marco Bertorello) The board indicating the level of the Mer de Glace glacier in 1990 is pictured in Chamonix on June 17, 2019. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)

The board indicating the level of the Mer de Glace glacier in 1990 is pictured in Chamonix on June 17, 2019. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)Even though the glacier has been retreating for years, it doesn’t become any less heartbreaking to see it. Because it feels like it’s melting before your eyes. Will my young nephews understand how beautiful and fascinating these glaciers were to us? How much of them will they get to see?

Once on the glacier, most of the time we climb in the silence of this lunar landscape. Except for an occasional helicopter or the regular rock fall that rumbles like an avalanche.

A part of the Mer de Glace glacier is pictured in Chamonix on June 19, 2019. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)

A part of the Mer de Glace glacier is pictured in Chamonix on June 19, 2019. (AFP / Marco Bertorello) A part of the Mer de Glace glacier is pictured in Chamonix on June 21, 2019. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)

A part of the Mer de Glace glacier is pictured in Chamonix on June 21, 2019. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)

We spend three nights in mountain huts. In the Requin hut, we find ourselves alone with the keeper. During the winter the hut brims with skiers, who stop to eat, but at the end of June, it’s empty, as there are few climbing routes that begin from here.

The Refuge du Requin (mountain hut) on the Mer de Glace glacier is pictured in Chamonix on June 17, 2019. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)

The Refuge du Requin (mountain hut) on the Mer de Glace glacier is pictured in Chamonix on June 17, 2019. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)The following day we climb down on the glacier to ascend its opposite bank. We share the Couvercle hut with about fifty other climbers. I get to work right away, firing questions at them. I am interested by all of it -- their routes, their worries, their dreams of future challenges.

The Couvercle Refuge (mountain hut) is pictured on June 19, 2019 in Chamonix. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)

The Couvercle Refuge (mountain hut) is pictured on June 19, 2019 in Chamonix. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)I find that the guides in training are the most worried of all -- the jobs that they are training for will likely be very different from what they’d imagined. Over the past several years, entire sections of the mountain have crumbled, as rising temperatures melt the ice holding the rocks together.

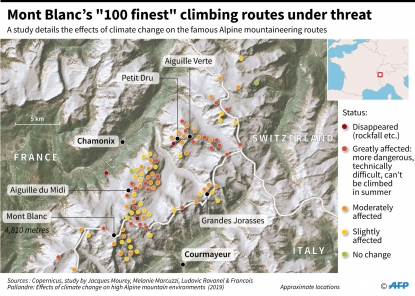

Take the Aiguille de Dru.

The legendary Italian climber Walter Bonatti climbed a new route on the southwest pillar of the Dru in August 1955 -- a six-day solo climb that helped propel him to legend status. That pillar collapsed 50 years later, in 2005. It is not the only one to have done so.

(AFP Graphics)

(AFP Graphics)Sometimes climbers find themselves ascending routes that are rumbling underneath -- a warning of an impending collapse. How unsettling, this impression that the rock holding you up could fall from under your feet. Like in a bad dream.

That evening, Marco poses a tripod outside to take a long exposure shot of Mont Blanc. I love these types of pictures, which capture the arcs of the stars, against the background of the Grand Jorasses wall, 1,200 meters high, topped with two triangles that remind me of milk teeth.

A night view from the Couvercle Refuge shows the Mont Blanc illuminated by the moonlight on June 18, 2019 in Chamonix. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)

A night view from the Couvercle Refuge shows the Mont Blanc illuminated by the moonlight on June 18, 2019 in Chamonix. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)Cute, until you think of the feats of climbing they’ve seen. Including dramatic winter ascents of this north face where climbers have lost their lives.

We go to bed around 11 o’clock at night, the very last ones. Most climbers go to sleep right after dinner, which is eaten early in the mountain huts, between 6 pm and 7 pm. That’s because most of the climbing parties leave in the middle of the night for their routes -- at midnight, three o’clock, five o’clock in the morning, depending on the route. Snow bridges weaken and become dangerous as they warm up in the sun, so most climbers like to be done with their route by early afternoon.

A part of the Mer de Glace glacier is pictured in Chamonix on June 18, 2019. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)

A part of the Mer de Glace glacier is pictured in Chamonix on June 18, 2019. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)The next day we climb hundreds of meters on ladders to arrive at the Charpoua hut, a small house that was built more than 100 years ago and where 30-year-old Sarah is the host for the summer, along with her five-month-old baby.

Everything is simple, peaceful and warm here. We take off our shoes on the flat rocks leading to the front door. We drink tea. Yann stretches on a flat rock to take a nap.

Aspiring Mountain guide Yann Grava takes a rest near the Mer de Glace glacier at the Charpoua Refuge (mountain hut) on June 19, 2019, in Chamonix. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)

Aspiring Mountain guide Yann Grava takes a rest near the Mer de Glace glacier at the Charpoua Refuge (mountain hut) on June 19, 2019, in Chamonix. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)We take turns holding the baby as Sarah prepares dinner. Nettle soup, risotto and chocolate cake for dessert. The other guests are a group of young climbers with their guide and a solo German student, his ruck sack filled with philosophy books.

The bathroom is a hole between two rocks, above the hut. You have to climb there, holding on to a rope strung to prevent any accidents. We’re at 2,800 meters.

In the early morning, we step out of the hut, one by one, to a grey and stormy sky. It feels like we are inside a cloud. We need to hurry back down the mountain and cross the glacier to get back onto the train that will take us to Chamonix. Hopefully we will avoid the rain. Or most of it.

“Good luck with going back to the city” Sarah says, smiling generously. She knows how hard it is to readapt to city life, the crowds, the noise, the bustle. How hard to walk away from this paradise, perched high up in the mountains.

Sarah Cartier, guardian of the Charpoua refuge on the Charpoua Glacier, walks near the refuge in Chamonix-Mont-Blanc on June 19, 2019. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)

Sarah Cartier, guardian of the Charpoua refuge on the Charpoua Glacier, walks near the refuge in Chamonix-Mont-Blanc on June 19, 2019. (AFP / Marco Bertorello)